![Image by [rom] Asian fan](https://www.ianwelsh.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/japanese-fan-by-rom-199x300.jpg)

Image by rom

The Geithner Plan, combined with the other steps taken by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury, make fairly clear the Obama administration’s plan. The sardonic summary would be “to continue the work of Hank Paulson”, but the more serious one would be, “we’re going to throw money at this problem untill it goes away.” The end result will be riptide inflation, and an economy that suffers from the Japanese sickness where the good times just never, ever, seem to return.

It is unclear how much money has been spent, guaranteed and loaned at this point. Given that back in February the number was $9.7 trillion, and that trillions have been committed since then, I think it’s safe to say that we’re over $12 trillion. This is a lot of money. The entire US GDP for 2008 was about $14 1/2 trillion.

The Fed has even decided to buy treasuries, which is the absolute definition of “printing money” since it amounts to one part of the government funding the other part of the government.

All of this money is going to land somewhere. What we are going to see is another bout of riptide inflation, where some parts of the economy (such as wages and housing prices) are in deflation, while other parts are inflating. My guess where the money is going to land? Oil prices again. It’s already begun. Put all that money into the hands of speculators and they have to park it somewhere.

Likewise when America buys its own treasuries, that means that the treasury bubble is going to start deflating. Private investors aren’t going to want to invest in a Ponzi scheme which is coming to an end. The US dollar has also very likely peaked, and we’re going to see it deflate over the next year.

All of this was avoidable. What should have been done was to take steps to deal with oil inflation: such as a 55 mph speed limit, 3 day weekends at major corporations, and so on. Such steps should have been instigated the second Obama took office, or put into the bailout bill or the stimulus bill.

The result instead is riptide inflation/deflation combined with a falling dollar and more difficulty financing this expansion in any way that isn’t nakedly printing money.

Then we come to the Geithner plan, which amounts to the federal government subsidizing hedge funds to buy toxic securities at overvalued prices using mostly money from the Federal Reserve and the FDIC in order to make sure they don’t have to ask Congress for money, since they know Congress would never give them another trillion and a half or so.

At the end of the day, the FDIC and Fed are backed by the US government, so any losses will have to be made up for by the American taxpayer. (In the old days, this was known as “taxation without representation”.)

There will most likely be losses, because a good chunk of the loans to hedge funds are non-recourse, meaning that if the value of the security goes down, it’s Uncle Sam who’s on the hook for most of the loss, not the hedge fund. Likewise the funds will be heavily leveraged, allowing them to pay higher prices than otherwise. Add to that the continuing collapse of housing prices and the economy, and you have a situation where the target is moving. As the economy gets worse, more and more people default on their mortgages, leading to a decrease in housing prices and thus the prices of securities built on top of housing.

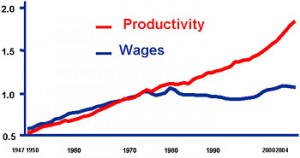

Which leads us to the stimulus bill. The Stimulus bill is not large enough or constructed well enough. So even if it works in a technical sense (gets GDP growth above zero) it’s probably not going to really turn the economy around in the ways that matter: recovering jobs and increasing wages. Without these two things increasing, and without a clear direction for the economy other than hedge funds receiving massively leveraged loans to play paper games—which worked so well before the crisis, you just know we should try it again—housing will keep decreasing, demand will not recover properly since consumers won’t have money to spend, and the assets underlying the financial crisis will continue to decline in value.

Because the government has loaned money to buy up the assets, and guaranteed much of the remainder of it, the government will be on the hook for the losses. (And by “the government,” I mean “your tax dollars.”)

What happened in Japan after their bubble is instructive. Instead of taking the toxic waste off their banks hands, or forcing write downs, they allowed zombie loans and zombie banks to sit around doing not much of anything. They also tried large Keynesian stimulus, but every time it looked like it might be working, they backed off. The end result was, and is, 20 years where the Japanese economy never really got good again. Short periods of modest growth were followed by recessions, over and over again.

Defenders of the Geithner Plan would say that we’ve learned from Japan’s mistakes. What we’re doing is taking the loans off the banks’ books, so we don’t have zombie banks. This misses the point, even assuming the government does eventually manage to move all the bad debts from the banks and into taxpayer hands, which is questionable since the losses are a moving and increasing target.

Why?—Because in macroeconomic terms it really doesn’t matter who has the debt, it doesn’t matter who is impaired. If the government has all the debt and winds up crippled, and government spending and loans wind up crippled, the effect is virtually the same as having crippled banks hanging around. The debt still has to be paid off.

The key difference here is between “paid off” and “wiped out”. “Paid off” means the full value gets paid back (minus whatever inflation the US has, which may be a lot). ” Wiped out”, on the other hand, is what would occur if private banks, firms and investors were forced to take their own losses. In that case, when the full value of the investor or firm was gone, any remaining value would simply disappear. If a bank goes bankrupt owing $200 billion, and the bankruptcy windups leave only $100 billion of proceeds, then the remaining $100 billion goes away. Yes, that $100 billion may wipe out some other people, but it’s done. It’s over with. It’s finished. You can’t get blood out of a stone, and when a firm or person is wiped out, they’re wiped out.

Instead the decision has been made, in effect, to pay back the full amount of the losses—and not to force those who made the bad bets to pay them back, but to put as much as possible of the losses onto the government and make taxpayers pay them back.

Since we’re talking about trillions of dollars of losses, in a declining economy, that means impairment of both government and private spending for years to come.

The end effect will likely be little different than what happened in Japan, with the exceptions that the US may see significant inflation, and that as net importer rather than a net exporter, the US probably can’t keep this up for 20 years. Which means that at some point in the future it will either have to default on the debts, inflate them away or have a financial collapse.

None of this is necessary, and there are still ways thing could be done better. The administration is set to announce their regulatory reforms next week. If those reforms are thorough and complete, ending the existence of “too big to fail firms”, sharply increasing tax progressivity and putting firm limits on leverage, then perhaps the pain to come will be worth it, if only because steps will have been taken to make sure it doesn’t happen again. But if real regulatory reforms aren’t put in place soon, the future will be bleak indeed.

The Economist’s View explains how the banks are going to drive a bunch of Brink’s trucks through the holes in

The Economist’s View explains how the banks are going to drive a bunch of Brink’s trucks through the holes in ![Image by [rom] Asian fan](https://www.ianwelsh.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/japanese-fan-by-rom-199x300.jpg)