I’m not exactly old yet, but I’m no spring chicken, and as a child and teenager in the 70s and 80s I read a lot of books from previous generations. I still read a lot, though not so much as when I was younger, and the non-fiction has changed. This isn’t surprising as writing changes with the times, but I think it’s generally become worse.

Oh, writing is smoother, as a rule. It’s Gladwellian. Contemporary non-fiction has lots of anecdotes and fuzzy feelings, lots of profiles of the people affected by whatever they’re writing about, lots of little details about the key thinkers. Many would argue contemporary books are better written, because they connect with people by making the stories personal.

I suppose they do. But they’re also disconnected. Most books today should have been 10,000 word magazine articles. There’s not enough meat: there’s fluff and detail on one issue or a small cluster of issues, but there is very little wide-ranging intellectual context. You can read a book on how important it is that everyone share in economic gains, or how people are risk averse, or how smart crowds are (or aren’t), or how people can’t think properly in time and how bad most people are at statistical thinking, or you read a book about how just a few resources can make a difference in history, and it’s all very well, but there’s no context. There is no world view.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing, and want more of it, please consider donating.)

As a result, these books become factoids. Because they either don’t sit a coherent world-model, or because they don’t state their world model, most people can’t really integrate these books usefully, because they don’t read enough books, they don’t spend enough time thinking or talking about what they read, and they don’t understand the premises underlying the world view. They have no model of cooperation or competition and how the two go back and forth, they don’t understand generational trends, they don’t understand the rhythms of technology; they understand neither conditioning (nurture) nor nature, nor how those two interact.

This isn’t people’s fault. This stuff isn’t taught in school, and it’s barely taught in university; when it is taught in university it’s rarely taught well or with proper attention to the assumptions of models. The disciplines which teach this stuff best, only do so rarely and are either despised (sociology), ignored (anthropology) or the discipline itself despises those who do integrative work (history).

People don’t know how to think. Despite all the talk about thinking, it isn’t taught because it’s hard to teach, and because employers don’t actually want employees who know how to think on their own (such people are endlessly annoying as subordinates, and executives are chosen largely for knife-fighting skills, not strategic ability, despite what the business books would have you believe).

Specialization can be useful, but before you go narrow, with rare exceptions, you need to go broad. You need context and a model, a schema into which to fit the facts. Modern non-fiction generally wastes half of its words on verbiage—creating an “emotional connection” without actually providing that context. As a result, in order to form a world view, one has to read a vast swath of books, throw out what isn’t useful and put what’s left into a coherent worldview, and do it largely on one’s own.

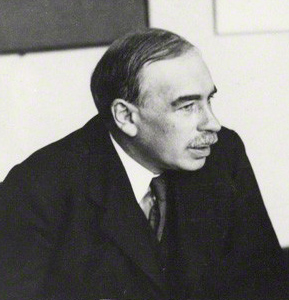

As a result you are far better off reading books like Jane Jacobs “Economy of Cities” and “Cities and the Wealth of Nations” or anything written by Max Weber, than almost anything published by younger authors in recent years. Nineteenth and early twentieth century authors writing on Empire speak more eloquently to strategy and growth than our current “international affairs experts”, and Keynes, for all he is abused, is far more insightful than most of those who either slag him or claim to follow him while doing what he would not have done.

Of course there is a place for books on narrow subjects, a place for non-fiction books which tug the heartstrings. But the true non-fiction classics, the books that are read and re-read, right or wrong, are generally books with great grasp and reach (The Prince, the Protestant Ethic, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life). And those books give people enough to work with, enough to understand, and speak to something large in society, something that matters: how to rule, how progress occurs, what religion is. You may reject them, as many have rejected all three of those (or Jacobs’ work), but they had reach and grasp and ambition and they spoke large about how the world works.

A book which tries to explain any part of the world must both have integrative ability and context. If it is not clear what is not explained by your theses, then your theses have failed. Everything cannot be explained by any one theory, whether that be self-interest (Darwinian reproduction or Economic utility) or more ancient (but still strong) theories about the will of God.

Let magazine articles be magazine articles. Let books be books, and let them try to shine light on enough of the world to matter.