(Just so no one misunderstands, this is Mandos writing, not Ian.)

Over the years I’ve collected a laundry list of potential problems that left-wing movements have in obtaining and exercising official power “through the system” in developed Western societies, but at least two of them have to do with the question of personnel and talent. These are problems that that manifest themselves both in the way that movements operate in the electoral space and then again reveal themselves if the progressive-leftist party gets really lucky and manages to hold official power. Some of them apply to populist right-wing movements too (but I think less so; the reasons for this we can leave to another day) and is at least a contributing factor to the extent to which the neoliberal order appears so crisis-resilient.

(1) Personnel for Getting into Power: We live in a mass media society where cheap communications means that messages are propagated very quickly. This means that almost all political campaigning is going to involve an aspect of mass advertising and marketing. I know that a lot of lefty people for obvious reasons have a bit of an allergy to the idea of political ideation as selling something, but unfortunately, that’s what it is. Selling stuff is a profession, talent, and skill.

The neoliberal establishment side of the equation has a lot of money to attract the kind of talent who can sell stuff. But that’s true of everything: The left always lives with a headwind of money that favours the establishment. What is more fundamentally difficult, however, is that the neoliberal demeanour has a very natural and smooth affinity to the notion of selling and is very deeply founded on the idea of competing psychological influence over individual choice; in fact, it openly celebrates this as a cornerstone of its fundamental political truth. The modern left, on the other hand, views advertising and marketing as an attempt at corrupting individual authentic choice. But in an environment of technologically-accelerated information dissemination, there’s no escape from selling political ideas and from a need for the talent required to do that. It seems unlikely to me, however, that, money aside, the sales talent is in large numbers going to abandon an ideological affinity for the governing neoliberal attitude.

(2) Personnel to Run the Show: Once in power, the problems have only started. Large industrial societies actually require a great deal of technical skill to run, both on matters of economy and finance as well as general administration and regulation. While leftists deride the prognostications of academic economics, there are nevertheless technical skills and concepts that are still required to have a modicum of control. Unfortunately, most people educated in these disciplines were also made sympathetic to neoliberalism. We saw in the Greek crisis that there was a layer of Greek bureaucracy that actively resisted the original form of the Syriza government. That is partly class interest — but a lot of “technocrats” genuinely believed that they were doing a good deed from preventing what they thought was stupid or impossible policy from being implemented, rather than respect democratic decision-making or question the political assumptions they take as positive truths. This is potentially a deeper and more difficult problem than (1).

The problem of finding technocrats willing to administer a moderately left-wing, post-neoliberal state feeds back into the original problem of electability. If the public (quite reasonably) gets the sense that left-wing parties simply lack the expertise to make existing systems work on a day-to-day basis, they’ll choose a seemingly better-administered political outcome, even if it actually represents long-term decline.

I won’t pretend to have immediate solutions to these problems. But I think they aren’t very closely discussed in these sorts of environments.

I am on the record as having very little use for hope. Barack Obama’s campaign cemented my view, with lots of talk of “hope and change,” centered around a politics which was going to be neoliberal centrist at best. And that’s what it was.

I am on the record as having very little use for hope. Barack Obama’s campaign cemented my view, with lots of talk of “hope and change,” centered around a politics which was going to be neoliberal centrist at best. And that’s what it was.

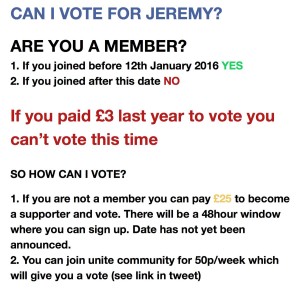

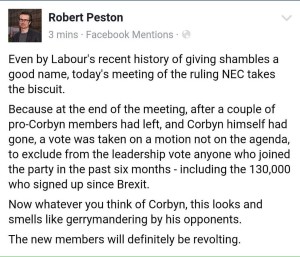

So, both sides got something. Corbyn is on the ballot, but

So, both sides got something. Corbyn is on the ballot, but