Michael Bloomberg

So, Michael Bloomberg has spent $300 million, and, by some polling, is now tied for second place in the Democratic primaries with Joe Biden, whose numbers are collapsing.

Bloomberg is worth about $63 billion.

He entered the race to defeat Sanders. He considered entering the race in 2016 until it became clear that Clinton would be the nominee.

This makes perfect sense, because Sanders tax plan will cost him billions. He can spend ten times as much as he has, and it will still be a good investment.

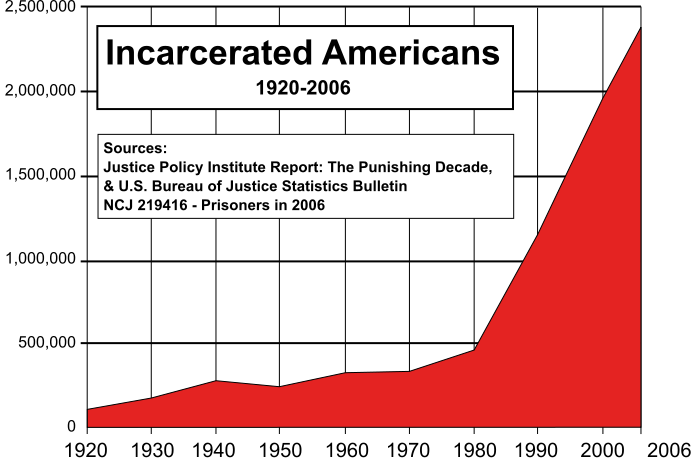

The thing about Trump was always that he was a symptom of a disease. It’s hard to say exactly when the disease started, but serious symptoms started showing up after the elections of Reagan and Thatcher. Wage increase rates collapsed, stock markets and other asset prices rose much faster than inflation, regulations were gutted, people were thrown in jail at a ferocious rate, and unions were smashed.

Strikes involving more than 1,000 workers

Inequality took off, and over time this created “multibillionaires.” They used their money to buy politicians, and, through those politicians, they bought policy. They slashed tax rates on corporations, rich people and their estates, and so on to the bone. They increased subsidies for the rich, while they cut subsidies for the poor and middle class, in relative terms.

The Federal Reserve (all of whose governors are political appointees), acted aggressively to keep wage increases at or under inflation, and targeted inflation rather than job growth. Good working class and many middle class jobs were off-shored and outsourced. Some of these processes had started before Reagan, such as offshoring and cutting top marginal tax rates (JFK foolishly did so, but then he was the son of an oligarch), but they went into overdrive after 1980.

From ’33 to ’68, the general trend was for the percentage of income controlled by the wealthy to decrease relative to the percentage controlled by everyone else. In 1968, that reversed, but 1980 is when it was locked in.

Money is, of course, power. Anyone who denies this is tediously stupid, given that almost all of us have spent most of our lives doing shit we wouldn’t do if we didn’t have to to get money. (Getting other people to do shit they don’t want to do but that you do want them to do is the very definition of power.)

So, the oligarchs, aided by the huge concentration of companies into oligopolies, have come to own or control vast amounts of wealth. They passed a law that defined money as free speech, and now that the political class has proven incapable of handling a left-wing populist, an oligarch is stepping in directly, because his class’s lackeys, like Biden and Buttigieg (and indeed most of the field), are incompetent.

Bloomberg is an oligarch. He’s racist, sexist, and arrogant. He had New York’s laws changed so he could have a third term. He is competent and ruthless. In most respects, he is far more dangerous than Trump–even though he is for some things the left likes, like birth and gun control. Trump is good at demagoguery, but he isn’t a competent executive.

Bloomberg IS a competent executive. As he joked when asked about having two billionaires in the election, “Who’s the other one?”

(He also has massive interests in China and has done their bidding in the past, a fact the hysterical Russia-Gaters might note.)

My guess is that Bloomberg can’t win except through a brokered convention. The plan may be to deny Sanders an outright majority, then combine against him. Doing so will break the Democratic party. Remember that the Clintons still have the most power over the Democratic establishment, and Hilary hates Sanders with a vindictive passion, while she is on good terms with Bloomberg. Obama, who also still has power and influence, seems more ambivalent, but he’s never liked the left. On the other hand, reports are that he’s dispassionate and recognizes that denying the vote leader the nomination will damage the party.

If Bloomberg does get the fix in, who will win in a Bloomberg/Trump match? I don’t know, but while Bloomberg is more competent as an executive, my feeling is that Trump’s unique strength as a demagogue will be the deciding factor in outmatching Bloomberg. The question then becomes whether Bloomberg’s money and organizational abilities can outweigh that.

Trump has increasingly been acting against the rule of law. He always was, starting with emoluments violations, but now that he was impeached and not convicted, he feels immune to Congress’s censure.

Trump also HAS TO WIN. If he loses, he will be destroyed by his enemies in New York, in various criminal investigations. They will take him down and destroy him. He understands this.

So, it’s oligarch vs. left-wing populist to see who gets to take on the minor oligarch, criminal, and current president Donald Trump, who knows that a loss means the end of his good life and the destruction of the minor empire he has built.

The only possible good outcome for most Americans is a Sanders win. No other path leads anywhere decent.

This is likely be the nastiest election cycle since the Democrats deliberately sabotaged McGovern.

For approximately the same reasons.

It’ll be horrific, and the outcome will control whether many people live, die, or have good or terrible lives. I suggest getting some hot dogs. If Rome is going to burn, you may as well roast wieners.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

I have a friend who is a serious meditator. For many years, when someone asked him to help them become enlightened, he would teach them a simple meditation, then instruct: “Do that for six months, every day, for one hour. Then return.” He called it “the very minimum required.”

I have a friend who is a serious meditator. For many years, when someone asked him to help them become enlightened, he would teach them a simple meditation, then instruct: “Do that for six months, every day, for one hour. Then return.” He called it “the very minimum required.”