“War is nothing but a continuation of politics with the admixture of other means.”

“War is nothing but a continuation of politics with the admixture of other means.”

— Clausewitz, On War

The first and most fundamental principle of warfare is to know your goal. This applies to any type of war, anywhere, at any time, no matter what tactic is used.

Last year (this is a reprint, but one most readers probably haven’t read) , I was one of the first people to predict that Israel would lose to Hezbollah — because Israel’s stated goal was to destroy Hezbollah as an organization. Given that during a nearly two-decade occupation, Israel had been unable to destroy Hezbollah, it was laughably obvious that Israel wasn’t going to succeed this time. (It turned out that the magnitude of their loss was greater than I expected.)

In the Iraq War, the US has a similar problem: The goals that were achievable have been achieved (overthrowing Saddam). But the goals that remain are unclear: creating a democracy friendly to the US, establishing permanent bases, making sure western companies have the oil contracts. These remaining goals are probably not possible to achieve with the amount of military force and spending the US is willing to allocate. Therefore, it has been clear for a long time (since before the invasion) that the US would not “win” the occupation in any real sense of the word. Indeed, at this point, the US is reduced to praying it can leave and not have the country crack up in a hot civil war. That goal might be achievable.

So it is with guerrillas. Guerrillas have to know what they can do, what they can’t do, and what they want to do. The primary virtue of guerrillas is that it is hard to wipe them out. The primary weakness of guerrillas is that they aren’t all that good at straight up fighting; as a rule, a competent regular army will routinely hand out loss after loss to guerrillas. Guerrillas have to be content with picking off isolated units, with causing pinprick damage like bombs and snipers, and with disrupting weakly defended supply and rear units. But in straight-up firefights, with very rare exceptions, it’s usually pretty unpleasant to be a guerrilla.1

We can take Clausewitz a step further. War is less the continuation of politics than the failure of politics. Nations and people engage in war when they feel they can get something they want more easily or advantageously with force than through other means.

If people feel that the occupation of their country won’t end peacefully, then war is inevitable. If certain groups wish to impose their religion, and know that it will not be allowed, then war is a route to their goal. If people want law and order, and occupation forces are unable to provide it, then a new government is necessary, and if one cannot be obtained through peaceful means, then it may be obtained through violent ones.

The failure of politics leads to war. The failure to provide law and order, the failure to rebuild infrastructure, the failure to provide belief in a promising future, the failure to align the interests of the occupation with the interests of the population…all of this sets up the preconditions for guerrilla warfare and rebellion.

Guerrillas in Iraq, for example, were fighting for a good position when the US leaves. This was clear in the pattern of attacks, which throughout the war have been much heavier on opposing Iraqi groups and Iraqi “government” forces than they have been on Coalition forces. Enough pressure has to be kept on the US to make the US leave, but the guerrillas know they cannot defeat the US in conventional terms. They can only cause more attrition than the US is politically capable of handling. So the goals of the various Iraqi armed groups might be said to be: “To convince the US to leave by making the cost of staying too high, and to be in a good position to fight for or negotiate for our place in Iraq after the US has left.”

In Palestine (another guerrilla war, for all that it is not called that), the goals of the two sides are as follows: For Israel, to crush the Palestinian resistance while establishing facts on the ground which will allow them to impose the most favorable settlement in a two-state solution possible; For the Palestinians, to not let the Israelis win.

Note that the Palestinian goal isn’t really to establish a Palestinian state. The Palestinians will take one if they can get a viable one, but they aren’t in a position to really pursue it. The goal is to not lose to the Israelis. (This is one reason why Arafat walked away from Clinton’s talks.) The Israelis have been occupying Palestine for decades now. They can clearly hang on for a long time. They aren’t going to be “forced” out; the Palestinians don’t have what it takes, and the Israelis have a high tolerance for low-level attrition losses.

The Palestine and Israel situation points out something important about the nature of guerrilla warfare: Guerrilla warfare is the strategy of the weak vs. the powerful. Palestinian losses and Iraqi insurgency losses are much higher, respectively, than those of the occupying forces. They always have been. The guerrilla’s equipment is not as good. The guerrillas, in most cases, are not as well-trained. They aren’t nearly as well-organized. They are just not as good at fighting and killing. In fact, the superiority of the coalition over the Iraqi insurgency, or of the Israelis over the Palestinians, is so striking that one wonders how it is that neither can actually really defeat their enemies.

Let’s move to that next, with a quote from the greatest guerrilla leader of the 20th century, Mao Tse Tung:

“Many people think it impossible for guerrillas to exist for long in the enemy’s rear. Such a belief reveals lack of comprehension of the relationship that should exist between the people and the troops. The former may be likened to water, the latter to the fish who inhabit it. How may it be said that these two cannot exist together? It is only undisciplined troops who make the people their enemies and who, like the fish out of its native element, cannot live.”

– Mao Tse Tung, On Guerrilla Warfare

The relationship between locals and guerrilla troops is the most important point in Mao’s entire essay, and indeed the most important thing you need to know about guerrilla warfare, occupations, terrorism, and insurgency. If the movement has the support of the population, they cannot be destroyed. Period. No matter how many you manage to kill, there will always be more. Now, support doesn’t mean answering affirmatively to the question “Do you prefer the guerrilla movement” in a poll. It means practical support: Are locals willing to feed guerrillas, hide them, and act as their ears and eyes? The general estimate is that if a guerrilla movement has between 10 percent to 20 percent of the population of an area behind it, until you can break that support of the population for the guerrillas, any victories over them will be purely temporary.2

This doesn’t mean national support. For example, if 20 percent of the population of California supported a violent secession movement, that would be sufficient to allow it to operate relatively successfully. For much of the occupation Iraqi, Shia have mostly not been shooting at Americans, but Iraqi Sunnis have supported more than enough insurgents to keep entire provinces in anarchy.

Let’s examine what having support means. If you’re a guerrilla leader, you must do everything possible to build the support of the population. In Iraq, this has meant that such law as is provided is often provided by various militias; if someone rapes your sister, steals your car, or murders your son, you go to militias for help, and they help you. Sadr helped put some power back on line for Sadr city. But more than positive things, what it means is making sure that the enemy does horrible things to the population — but not too horrible. The killing of the mercenaries in Fallujah, for example, was a classic guerrilla move; carefully staged (including the pictures, which are clearly stage-managed) to cause an American overreaction. That overreaction occurred, Fallujah was eventually effectively destroyed, and horrible atrocities occurred. Sunnis then learned to hate Americans even more. On a lesser scale, every time an American soldier frags some old man at a stoplight, every time a girl is raped, every time there is “collateral” damage that takes out a wedding, all of these are grist for the guerrilla propaganda mill. Mao is relentless in his writing that one of the major jobs of guerrillas is propaganda, and that every large guerrilla unit (bearing in mind this was in the early 20th century) should have its own press.

It should go without saying, but apparently doesn’t, that if you don’t want to arouse more hatred, then doing things like torturing people, sweeping up large numbers of people who aren’t associated with the insurgency, and locking them up in a prison associated with torture from the old regime is working against your own goals. It’s the equivalent of handing the guerrillas supporters on a silver platter. Any atrocity that is not sufficiently large enough to make a specific person think, “There’s a good chance this will happen to me,” isn’t just immoral, it’s stupid. It is aiding and abetting the enemy.

As an army fighting an anti-insurgency campaign, there are two routes to take to deal with the population’s support for a guerrilla movement. You can try and win the population over largely with honey, or you can make the population so scared and powerless that they won’t, or can’t, support the guerrillas. The second method is a heck of a lot easier, though the first method has been used successfully, most notably in the Malaysian Emergency.

Let’s talk about the easy way first. Scare and weaken the population into no longer supporting the insurgency. The primary method here is mass killing, and removal of the population to camps. If a city (like Fallujah) is a problem, you destroy it entirely, and you kill everyone in it — or at least every fighting-age male. This is one reason why US marines would not allow men out of Fallujah in the run up to the final assault. Do this often enough, and people get the message that supporting the insurgency is a really bad idea. And if you’re willing to kill hundreds of thousands or millions of civilians, you’re bound to get a lot of the right people, along with a lot of the wrong people. Immoral? Of course, but it does work. Take other towns and cities which are troublesome, but not quite so bad, and move their populations to camps. This allows you to control the population in such a way that they can’t support guerrillas.3 Both of these methods were used by the US in the Philippines on a large scale. They worked. Wiping out a huge chunk of the population also worked for Russia against Chechnya, notable for inspiring enough hatred to spawn female suicide bombers, who were mostly avenging male relatives or lovers tortured to death by the Russians; and for Turkey against their own Kurds, a campaign notable for wiping out entire villages, killing the men, and raping the women. The camp strategy is currently being used by India against some of its indigenous guerrilla movements. A sufficiently ruthless commander could “win” the Iraq occupation in a few years, if given the green-light to commit massive atrocities and kill a few million Iraqis.

The ruthless strategy doesn’t work when you don’t have the stomach or moral imbecility for it (e.g., the US in Iraq), or when you don’t have the means to wipe out enough of the population (e.g., the Japanese in China). It also has the effect of wrecking the economy of the nation you do it to, which can be a negative, but doesn’t have to be. If you’re conquering a nation for its natural resources, you really only need enough natives to extract them, after all. And if there’s no other economy but your plantations, mines, and oil fields, then that just means the workers are cheaper.

The “kill them with kindness strategy” is harder to pull off. It requires more men on the ground, and those men have to have fire discipline. The attitude of US troops that they’d rather make a mistake and blow away an Iraqi family is the exact antithesis of the sort of fire discipline required to NOT alienate a population. You must be willing to take some losses you wouldn’t otherwise take in order not to hand propaganda coups to the guerrillas

You need more men on the ground because you must protect the population from the guerrillas. If you aren’t committing enough atrocities, then the guerrillas will either try and taunt you into doing so, or they’ll commit them for you; this is the method behind the apparent madness of car bombs and suicide vests. The guerrilla in this case is saying, “If you ever want peace and order, if you ever want to feel safe, you will have to let me rule because the enemy can’t stop me. The only group that can stop the killing is us, because we’re doing it, and the occupiers are too weak or incompetent to stop us.”

In a sense, this guerilla strategy is the mirror of the ruthless strategy. In the ruthless strategy, the anti-insurgency force says, “We’ll keep killing, torturing, and raping you in gross quantities until you stop supporting the insurgency.” When guerrillas do the same thing, it’s a retail version. (Although, as Iraq has demonstrated, the numbers can approach gross lots much faster than one would think. B52s aren’t needed to kill large numbers, they just make it easier.)

Safety is job one. If there is no safety in a country, the people will support whoever they think can provide it.

Job two is prosperity. The hard way requires that you flood the country with money, jobs, and prosperity. Important people (tribal leaders, Imans, village headman, etc) should be getting rich. Ordinary people should have jobs. Farmers should find that crop prices are up (support them if necessary, for God’s sake). They should recognize that they are better off under you than they could ever be under the guerrillas

The goal of reducing support for the guerrillas isn’t just about aid, it’s about informants. To break an insurgency, you absolutely must have informants. You need people telling you who are the cell leaders, warning you of attacks, etc. And you must be able to protect your informants. Every time I read that, in Afghanistan, some villagers who had accepted NATO help, or who were friendly with NATO, or who taught girls, have just been killed by the Taliban, I wince.

Job one in the friendly way is protecting your people. Your troops are expendable, but your allies — especially local influentials in the population — are not. It’s important to get this through one’s head: A soldier’s life is not worth more than a the life of a friendly local in an anti-insurgency campaign. Not if you want to win.

Create prosperity, maintain law and order, recruit informants, protect your allies.

So much for the strategy of an insurgency, pro or con. Let’s talk about the operational and tactical details, the stuff that determines whether Petraeus’s plan can work even in the short term, as just one example.

In general, guerrilla units disperse to operate: When the enemy is in over-extended defense, and sufficient force cannot be concentrated against him, guerrillas must disperse, harass him, and demoralize him.

When encircled by the enemy, guerrillas disperse to withdraw.

When the nature of the ground limits action, guerrillas disperse.

When the availability of supplies limits action, they disperse. Guerrillas disperse in order to promote mass movements over a wide area.

– Mao Tse Tung, On Guerrilla Warfare

When Petraeus flooded Baghdad with troops, what did the enemy do? They dispersed much of their force into the provinces. Dispersal operates at the highest geographic level like that, and at the smallest level. Let’s say you’re operating in urban environments and you encircle a group. They drop their weapons and disperse amongst the population. How are you going to capture or kill them unless people are either willing to point them out to you or you are willing to simply kill everyone? (Or every male, as the Marines did in Fallujah.)

Let’s say a guerrilla unit wants to move from city A to city B? Do they travel as a convoy? No, each man travels by himself, without weapons, in civilian garb, and once he reaches the city, they regroup and are rearmed by local cells or just by the local black market. You can slow this process down by the sort of methods the Israelis use, of dividing the country into cantons and restricting movement between them, but you can’t stop it entirely (and remember that the Israeli occupied territories are tiny compared to Iraq).

Let’s say there are no good targets. You simply don’t fight. But unless your enemy has enough forces to garrison every part of the country in such numbers that you can’t defeat any group in detail, you control all parts of the country where the enemy is not, and the population supports you.

What happens if the the anti-insurgency forces break up into smaller groups to pursue the guerrilla forces which have likewise broken up? Or what happens if you start putting small units in every little neighborhood, to provide law and safety? Sun Tzu and Mao tell us…

If we are concentrated while the enemy is fragmented, if we are concentrated into a single force while he is fragmented into ten, then we attack him with ten times his strength. Thus, we are many and the enemy is few. If we attack his few with our many, those who we engage in battle will be severely constrained.

– Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Guerrillas concentrate when the enemy is advancing upon them, and there is opportunity to fall upon him and destroy him. Concentration may be desirable when the enemy is on the defensive, and guerrillas wish to destroy isolated detachments in particular localities. By the term ‘concentrate,’ we do not mean the assembly of all manpower but rather of only that necessary for the task. The remaining guerrillas are assigned missions of hindering and delaying the enemy, of destroying isolated groups, or of conducting mass propaganda.

– Mao Tse Tung, On Guerrilla Warfare

So if the occupiers divide their forces, the guerrillas concentrate and attack in overwhelming force. Because guerrillas can move like fish in the ocean, which is to say, they can usually concentrate at the site of the attack without the defenders knowing because they don’t move as obvious formations of enemy troops, they will have tactical surprise, in almost every case. It is a testament to US military superiority (and air and artillery) that, despite multiple attempts to overrun various smaller US bases, the US has held on to them. But there is always a risk, because you can never tell when an attack is going to happen, and the enemy knows when you concentrate (they can hardly miss it, with the population as their eyes and ears) — but you can’t tell when guerrillas will concentrate and attack.

In addition to the dispersion and concentration of forces, the leader must understand what is termed ‘alert shifting.’ When the enemy feels the danger of guerrillas, he will generally send troops out to attack them. The guerrillas must consider the situation and decide at what time, and at what place, they wish to fight. If they find that they cannot fight, they must immediately shift. Then the enemy may be destroyed piecemeal. For example; after a guerrilla group has destroyed an enemy detachment at one place, it may be shifted to another area to attack and destroy a second detachment. Sometimes, it will not be profitable for a unit to become engaged in a certain area, and in that case, it must move immediately.

– Mao Tse Tung, On Guerrilla Warfare

Again, if a strong force is attacking, disperse, find a weaker force, and re-concentrate to attack it.

Let’s wrap this up, letting Sun Tzu, who wrote the first known treatise on military strategy, start us along the path:

Being unconquerable lies with yourself, being conquerable lies with the enemy. Thus, one who excels in warfare is able to make himself unconquerable, but cannot necessarily cause the enemy to be conquerable.

—Sun Tzu, On War

Guerrilla warfare is the strategy of the weak faced with the strong. It is also the warfare of an oppressed population against those who oppress them. These points can’t be stressed enough. Although a guerrilla movement needs nowhere near the support of a majority of the population, it can’t survive without substantial, popular support. The Taliban have many followers. So does the Sunni insurgency. So does Hamas. So did Hezbollah, when they were fighting a guerrilla war.

Whenever you are fighting a guerrilla movement of any power, you are also, effectively, at war with part of the population. On top of the strategic and tactical implications already discussed, this has moral implications that should be carefully thought through, and even more carefully as the percentage of support creeps up and past 50 percent, as it does in many cases. Does the will of the people matter? Do you have the moral right to force them to accept what you think is best?

This is the case even of movements at less than 50 percent. Perhaps the majority of the population doesn’t support the guerillas, and thus you have a moral mandate to fight them. But why is it that a significant minority is so angry they are willing to support this level of violence? If you don’t understand that “why,” not only will you have a hard time defeating them, but the phrase “tyranny of the majority” could have real resonance. Of course, the minority could be supporting the guerrillas because the guerillas have terrorized them into support, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they like you, either.

Guerrilla warfare is what the weak do when the strong have defeated them. It’s the moment when they say, “No, this isn’t over until I say it is.” At that point, you have a choice of putting the boots to their ribs until they submit to occupation, or you can try and convince them that fighting you isn’t the best path to the peace, prosperity, dignity, and self determination that all people want.

Or you can walk away, and let them rule themselves.4

War is indeed politics with an admixture of other means. Understanding those means, what their limitations are, what is required to use them and win, and the moral choices they will force on you, should be required of anyone who is in a position to commit a country or a people to war. Once let loose, the dogs of war often slip the leash of he who thought to control them.

Notes

Originally Published at BOPNews in slightly different form, back in 2004. Has been published in the Agonist and FDL at other points. One of my personal favorite articles I’ve written. Previous version at this site can be found here, but I’m reprinting so it goes out to email and RSS.

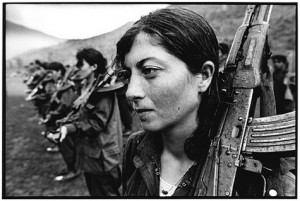

The picture at the top is of a female Kurdish soldier, almost certainly a guerilla, though I can’t say for sure. It is from this Kurdish gallery archive site, which is more than worth your time to visit.

Endnotes

1. Important aside: Hezbollah’s troops, while trained to operate as guerrillas, are regular soldiers. As one military analyst quipped to me: “What do you call light infantry trained to operate as guerrillas? Special forces.” Israel smashed its face in against a heavily-fortified, special forces army. Puts it in a new light, doesn’t it?

2. In the Revolutionary war, one estimate is that the rebels had the support of about a third of the population, the Tories about a third, and about a third just wanted all the guys with guns to go away. Note that the rebels did manage to field a conventional army, with the strong support of France. It is generally a good sign for an insurgency if it can support a regular army alongside the guerrilla resistance, again, because guerrillas can only win by wars of attrition (“To hell with it, it’s not worth it”), not through battlefield success. A regular army is not so limited.

3. Protecting the population may sometimes require setting up camps or fortifying existing villages. Because camps are used in the ruthless method as well, and because the ruthless method is used more often, they’re generally considered bad things. But they are usually part of the kinder anti-insurgency strategy as well, especially in rural areas.

4. The full text of Mao’s “On Guerrilla Warfare” can be found here. The section with most of the more generic advice (not particular to the Chinese/Japanese war) can be found here.

5. This isn’t always easy. For example, in Northern Ireland, the Brits would have loved to walk away. Problem was, the majority of the population wanted them to stay. Ouch.

If you enjoyed this article, and want me to write more, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.