By Tony Wikrent

How to give a good speech

Tim Harford [via The Big Picture 12-02-2024]

The art of good public speaking is often to say less, giving each idea time to breathe, and time to be absorbed by the audience. But the anxiety of the speaker pushes in the other direction, more facts, more notes, more words, all in the service of ensuring they don’t dry up on stage. It’s true that speaking in public is difficult, even risky. But the best way to view it is as an opportunity to define yourself and your ideas. If you are being handed a microphone and placed at the centre of an audience’s attention for 20 minutes, you’re much more likely to flourish if you aim to seize that opportunity. Everyone is watching; you’re there for a reason. So . . . what is it that you really want to say?

[TW: The ability to speak well in public is a skill that will probably become more and more important as we try to resist the Trump’s regime’s policies and actions. I have often regretted I have not learned public speaking while in high school and college.]

Strategic Political Economy

The Great Grocery Squeeze: How a federal policy change in the 1980s created the modern food desert.

[The Atlantic, via The Big Picture 12-07-2024]

…The structure of the grocery industry has been a matter of national concern since the rise of large retail chains in the early 20th century. The largest was A&P, which, by the 1930s, was rapidly supplanting local grocery stores and edging toward market dominance. Congressional hearings and a federal investigation found that A&P possessed an advantage that had nothing to do with greater efficiency, better service, or other legitimate ways of competing. Instead, A&P used its sheer size to pressure suppliers into giving it preferential treatment over smaller retailers. Fearful of losing their biggest customer, food manufacturers had no choice but to sell to A&P at substantially lower prices than they charged independent grocers—allowing A&P to further entrench its dominance.

Congress responded in 1936 by passing the Robinson-Patman Act. The law essentially bans price discrimination, making it illegal for suppliers to offer preferential deals and for retailers to demand them….

For the next four decades, Robinson-Patman was a staple of the Federal Trade Commission’s enforcement agenda. From 1952 to 1964, for example, the agency issued 81 formal complaints to block grocery suppliers from giving large supermarket chains better prices on milk, oatmeal, pasta, cookies, and other items than they offered to smaller grocers. Most of these complaints were resolved when suppliers agreed to eliminate the price discrimination. Occasionally a case went to court.

During the decades when Robinson-Patman was enforced—part of the broader mid-century regime of vigorous antitrust—the grocery sector was highly competitive, with a wide range of stores vying for shoppers and a roughly equal balance of chains and independents. In 1954, the eight largest supermarket chains captured 25 percent of grocery sales. That statistic was virtually identical in 1982, although the specific companies on top had changed. As they had for decades, Americans in the early 1980s did more than half their grocery shopping at independent stores, including both single-location businesses and small, locally owned chains. Local grocers thrived alongside large, publicly traded companies such as Kroger and Safeway….

Then it was abandoned. In the 1980s, convinced that tough antitrust enforcement was holding back American business, the Reagan administration set about dismantling it. The Robinson-Patman Act remained on the books, but the new regime saw it as an economically illiterate handout to inefficient small businesses. And so the government simply stopped enforcing it….

Why did Silicon Valley turn right? The “pounded progressive ally” thesis has limits

Henry Farrell, December 04, 2024 [Programmable Mutter, via The Big Picture 12-07-2024]

…The shifting relationship between the two involves- as far as I can see – ideas, interests and political coalitions. The best broad framework I know for talking about how these relate to each other is laid out in Mark Blyth’s book, Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century.

Mark wants to know how big institutional transformations come about. How, for example, did we move from a world in which markets were fundamentally limited by institutional frameworks created by national governments, to one in which markets dominated and remade those frameworks?….

As Mark puts it in more academic language:

“Economic ideas therefore serve as the basis of political coalitions. They enable agents to overcome free-rider problems by specifying the ends of collective action. In moments of uncertainty and crisis, such coalitions attempt to establish specific configurations of distributionary institutions in a given state, in line with the economic ideas agents use to organize and give meaning to their collective endeavors. If successful, these institutions, once established, maintain and reconstitute the coalition over time by making possible and legitimating those distributive arrangements that enshrine and support its members. Seen in this way, economic ideas enable us to understand both the creation and maintenance of a stable institutionalized political coalition and the institutions that support it.”

Thus, in Mark’s story, economists like Milton Friedman, George Stigler and Art Laffer played a crucial role in the transition from old style liberalism to neoliberalism. At the moment when the old institutional system was in crisis, and no-one knew quite what to do, they provided a diagnosis of what was wrong. Whether that diagnosis was correct in some universal sense is a question for God rather than ordinary mortals. The more immediate question is whether that diagnosis was influential: politically efficacious in justifying alternative policies, breaking up old political coalitions and conjuring new ones into being. As it turned out, it was.

[TW: “The Great Grocery Squeeze” that resulted from Reagan’s decision to stop enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act, proves the accuracy of Farrell’s and Blyth’s work. So also Stoller’s discussion of federal judge Carl Nicholsm below. This is all a reflection of civic republicanism being supplanted by liberalism as capitalism developed, allowing “sanctity of private property” to become a more powerful “economic idea” than “promote the General Welfare.”]

Read More

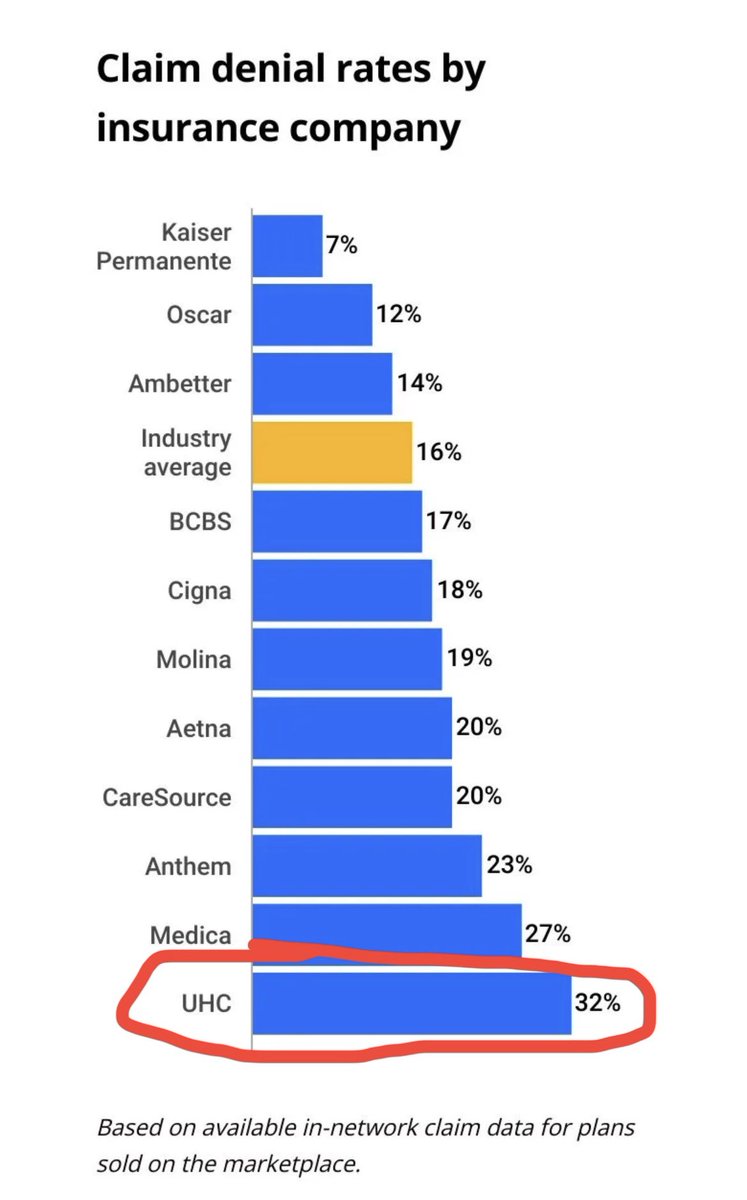

So, Mangione assassinated Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare, the US health insurance company with the highest denial rate in the industry.

So, Mangione assassinated Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare, the US health insurance company with the highest denial rate in the industry.