This is based mainly on “Crises and Decline in Credential Systems”, found in Sociology Since Midcentury, Randall Collins, 1981.

We’re currently in the late-middle stage of a higher education crisis in the West. This isn’t a worldwide crisis: the Chinese system is still in its expansion phase, but it’s very real here. Recently I was talking to a friend in Norway, who noted that most young people want a trades education and to avoid university.

I’ve noticed when discussing this that most people are resistant to the idea that this isn’t the first time it’s happened. We have this weird idea that before the modern era, there weren’t large post-secondary education sectors: that degrees and credentials from schooling are something new. This isn’t even slightly true: heck, if we had the data I’m sure we could find something similar in Ancient Egypt, and for sure the massive university systems of Buddhist India went thru more than one cycle. This before we even get to China, a civilization which was based on a credential system for something like two millennia.

But neither is it new in the West.

Schools produced standard culture (and standardized people, as far as that goes.) Culture allows the creation of longstanding institutions: not just the universities themselves, but bureaucracies of various forms, including corporate bureaucracies. It’s not an accident that companies demand degrees, especially for managers.

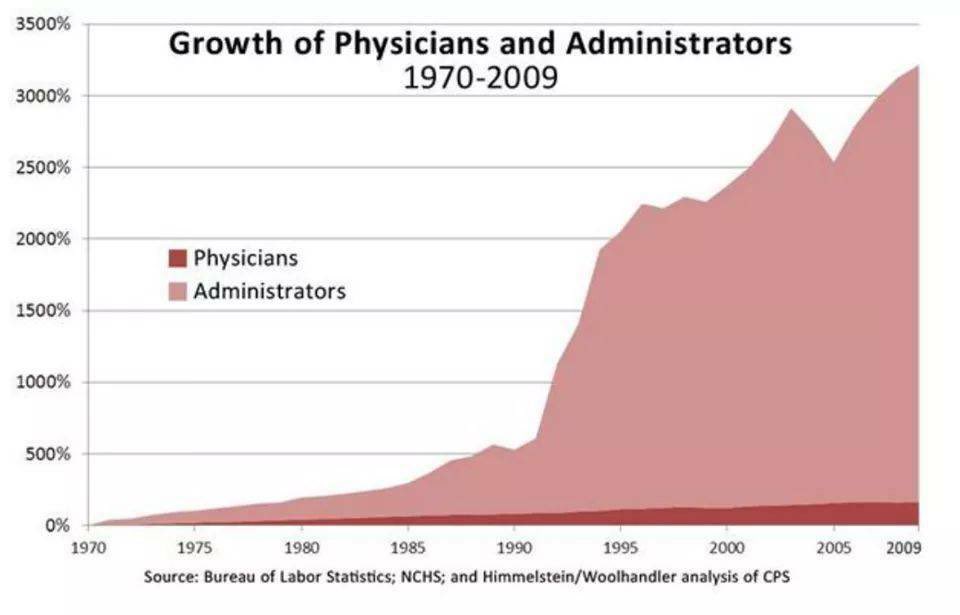

This culture creation is used in political competition. Think the medieval church vs. various kings, or the kings v.s their feudal lords, or Confucian scholar officials v.s hereditary nobility. In the modern world consider what happened when university trained, mostly Ivy league, degree holders took over the media, or the effect of MBAs taking over from engineers in companies. Boeing is a good example of the consequences, but so is the entire shipping of industry out of the US, and the enablement of China.

Education is one of the sinews of political conflict.

Universities (or credential systems in general) go thru four phases. All four don’t always happen, sometimes the cycle is stopped before it reaches its end.

Expansion. Lots of new students pour in. More institutions are created. Formal requirements for professions are credentialized thru the institutions. In the Medieval era this was civil law, canon law, medicine and theology. In the modern era it includes much more, but of particular note are engineers. During this period having a degree means an almost complete certainty of getting a job. Think of the 50s: a BA was all you needed to vault into management.

Cultural Production Outstrips Positions. An end to the easy early period. You have to compete for positions, there aren’t enough. Credential inflation starts: what once required a B.A. now requires an M.A. The amount of time for higher degrees gets longer and so on. (Back in the early 90s a friend taking a PhD in psychology told me that a PhD alone was no longer enough. Ten years earlier, it had been.) The price of getting an education increases, and in this and the third stage, it tends to skew more and more to the wealthy.

This, I note, has obviously happened in our society. Back in the sixties, education was practically free, now it requires a loan students may not pay off for decades, or ever.

All the positions are filled. (We are here.) There isn’t just a lot of competition, the degrees are increasingly worthless unless you also have clout from something other than education because the positions are filled. The number of people who live off the productive system but don’t contribute to it goes up.

This goes in phases: right now BAs get you nothing but a chance to apply and be rejected, and BA enlistment is falling, but STEM still offers a decent chance. (This won’t remain true in the West for much longer.) During this period alternate culture production really gets fired up: intellectuals who can’t get positions produce books, pamphlets, blogs, podcasts and so on. They attack academia and seek forms of legitimacy other than credentials.

Finally, collapse. The state stops enforcing monopolies, university enrollment drops and many institutions fail entirely. Other forms of cultural production become dominant.

The Medieval University Cycle

The rise really gets going in the 1100s, though some institutions are created earlier. By the 1200s they are accredited by the Church of the Holy Roman Emperor. This makes the credentials valid throughout Christendom, which no other higher credentials are. At this time both the papacy and various kings and principalities are expanding their administration, and there are tons of positions. As with the Confucian scholars in the early days, these administrators are used to expand central authority: feudalism begins its decline. In addition the monopoly of law, medicine and theology works against feudal nobles.

Every major pope from 1159 to 1303 held a degree in law from a university. One of the signs of the end of the reign of the medieval scholastics is when other ways of training come to the fore. In England in the 1400s, for example, lawyers no longer learn and OxBridge, but in London in what amounts to an apprenticeship system. By the 1500s OxBridge no longer teaches physicians, this moves to the Royal College of physicians and soon after the monopoly of clergy on medicine is ended.

The height of the system is significant: two thousand to four thousand students were enrolled at Oxford and Cambridge, for example. This is 4x as many, proportionally, as were enrolled in Elizabethan England and as a proportion of the population the medieval height wasn’t surpassed until after 1900. At this height at least five percent of the male population attended university and it could have been as high as 10%.

The medieval system, note, goes into decline fifty years before the black death: so it wasn’t caused by declining population.

As the medieval system goes into decline, the humanists rise. They work outside of universities often as publishers or authors and rely on noble patronage. They mock the old academics as rigid, fusty and out of date.

But the decline isn’t good for ordinary people: as mentioned in our own case, education becomes less and less available unless you have money and stops being a major way for people to rise. This was very much true in the medieval university decline: at the beginning many poor individuals could attend, but as time went on this became much less true.

Signposts of Decline

- smaller institutions folding. (The closure of many of the small liberal arts colleges in our time, for example.)

- a fall in the number of students.

- decline in number of institutions.

- loss of monopolies over credentials.

- widespread attacks on what is taught and how it is taught. (We see a great deal of this now, and it has progressed to politicians passing laws.)

- Increase in the cost of education, with poorer students being cut out.

- Cheap degrees which are mere formalities: degree mils and so on.

Note that phases three and four also can feed into political instability. In recent years Peter Turchin has popularized this, and many think he created the idea but it’s long been discussed as important in revolutions such as the French and Russian ones. People who are highly educated but didn’t get the positions they wanted are vastly destabilizing: they feel betrayed and they have the tools to fight ideologically and often the understanding of how to administer movements and other organizations.

Raise someone’s expectations, train them, then let them rot in poverty and you’ve made yourself a potential enemy.

These cycles are dead common. Collins identifies a number, just in the West:

- The Medieval cycle – starts in the 1100s, peaks in the 1200s, over in most places by the 1400s.

- English cycle from 1500-1860

- Spain from 1500-1850

- France 1500-1850

- Germany 1500-1850

- US 1700-1880

The various national ones, though they start at about the same time, other than in America, are separate and have different patterns of rise and decline. Not all of them go all the way: the American universities never go thru phase four, for example.

Education Systems Rise and Fall like all else in human society. What is happening now in our system is very similar to what has happened before and if we want to understand what will happen to our system, the best way to know is to see what happened before. It will never be a one-to-one match: the details will differ, but the pattern will hold.

The obvious thing to do for those who want to slow the fall and end it before collapse is to figure out what sort of training they can produce which isn’t in oversupply. For individuals the question is where the new form of cultural production is and how to legitimize it and reap the benefits of that legitimization. One might wonder if the rise of podcasting intellectuals who use their celebrity to sell their books is a fad, or a sign of something greater, for example. I may return to that in the future.

In the meantime: it’s all happened before.

Bukko Boomeranger

In addition to Turchin’s theory of collapse here, I also get a whiff of Cory Doctorow’s enshittification dynamic of decline applying to university education.

Your expansion phase is like Doctorow’s Enshittification Stage 1 when value is being supplied to users of a service. Earn a degree, get a good job! The “outstrips” phase is analogous to Enshit Stage 2 when more value is shifted to businesses that use a service, leaving less to the user (the students). Outstrip/Stage 2 is great for corporations because they have a lot of trained potential employees to choose from; less good for the students because they’re in a tight market. The “Filled” phase is like Stage 3 Enshittification, where much of the value now goes to insiders at the service. Instead of investors and corporate insiders cashing out stock options from the now-enshittified business, in this case it’s the university deans and other functionaries pulling high salaries from overstaffed academic offices while professors get crap pay. Enshittification Stage 4, where everyone decides they hate an Internet app and stop using it, is like when potential students decide that there’s no point chasing a degree in Gender Fluidity Studies because plumbing pays more for fluid-y stuff.

Universities — so smart that they’re smashing themselves!

bruce wilder

I have long been interested in the British Civil Wars of the 17th century. The 16th century sees a remarkable rise of primary education, which is followed by waves of secondary and tertiary education that bring the level of education in Shakespeare’s London to a level it would not reach again until the red brick wave of the late 19th century. The English language transforms rapidly. The Civil Wars themselves are attributable in large part to the breakdown of official censorship and the multiplication of sects and ideologies, but even if that account of causality fails, the political chaos becomes a hothouse for political discourse that reaches thru out the society. The contrast with the social class sclerosis of the 18th Century is stark in retrospect. Intellectually, religious passions eventually yields to the Enlightenment and blasphemy becomes merely impolite.

Jefferson Hamilton

Podcasting “””intellectuals”””.

Carborundum

I would really like to see the math behind the estimate that 5 to 10% of the male population attended university.

Willy

It took me a while to understand that higher education was primarily about making networking connections, second about earning a diploma status badge, and lastly about earning practical knowledge beneficial to economies. I think of all the times I observed brilliant minds being denied entrance to prestige, while lesser minds had no such issues just because they had the proper connections. I think of the many ‘historic innovation greats’ like Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Frank Lloyd Wright, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs… among many others, who never earned a college degree, with most of them being notorious for using those who did earn degrees for their own advantage.

I”m not saying that college is worthless. If I was an army grunt doing war, I’d much rather my commanding officer be a West Point grad well-trained in the science of making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country, than just being another well-connected grunt.

What I was trying to describe is a system underlying the educational system, for the purpose of understanding the whys behind why our current system is so screwed up.

Why would higher education be allowed to become so prohibitively expensive? We allowed professorial salaries to barely keep up with inflation, while administration costs exploded, and government assistance radically declined. Seems pretty stupid to somebody trying to be an economic patriot. Is this all because the connected think all the good positions have been filled?

Oakchair

One of the problems is that education is no longer (arguable if it ever was) focused on developing students who can think, understand, and problem solve. Educations’ focus is money, conformity and obedience to the “experts” .

Ivan Illich in “disability professions” described how this leads to people who cannot function because they rely on an “expert” for everything. Parents can’t parent because they need a Ph.D expert to tell them how to do everything. People avoid a healthy lifestyle because the miraculous doctor will fix it despite that same doctor ruining millions of lives with opioids, vioxx, psych drugs, etc.

Creigh Gordon

Related: End Times, by Peter Turchin, focuses on overproduction of elites in the disintegration of political systems.

StewartM

Ian, you meant ‘degree mills’ in “Signposts of Decline”.

Excellent article. My only observation/question is, do you think that the growth of ‘credentialing’ is connected to our decline in competency? Here’s what I’ve observed:

As companies gotten taken over by the financial class, as MBAs (usually trained at so-called ‘elite schools’) took over companies, this resulted in a loss of both technical knowledge and a loss of appreciation of technical skills and the ability to evaluate them at the top. As these control who gets promotions and who doesn’t, this loss filtered down through the ranks (i.e., they promote those who think like them). It will take years before this loss seeps down to the first levels of management, but given enough time, it will.

I’ve sat on hiring teams. I’ve done interviews with job candidates. My job and that of people like me was to ‘grill’ the candidates on their technical knowledge, to see if the expertise they put down on their resumes was accurate (hint: it very often wasn’t, it was superficial experience). I could see the tension on our hiring teams, between the managers who now lacked a lot of technical knowledge and the technical people like myself. The managers were impressed with degrees, with school pedigrees, and they also tended to favor candidates (like themselves!) who wanted to jump to the managerial track at the first opportunity….another great manager!, they thought.

We technical people gave those same folks the big ‘thumbs down’. 🙂 Their academic pedigree didn’t matter to us, it was their technical knowledge ability to reason through technical issues. BTW, we also had candidates eat lunch with a group of selected hourly employees, and the hourly employees (in part, to see ‘how does this candidate treat and talk to people who don’t have degrees or have less prestigious degrees than they?”) The hourly employees always voted with us technical folks.

(Oh, and talk about the ‘standard culture’ thing–one of our candidates I thought was simply brilliant, even though I didn’t think he was a great fit for the job position. He understood the instrumentation and the technology so well he had made significant tweaks to it during his tenure at other positions. He had truly deep knowledge of his area of specialization. But the managers didn’t take to him as a) his academic pedigrees wasn’t ‘elite’ enough; and b) he wasn’t a punctual person. He was twice late to interviews and in his presentation. To me, that’s a pretty trivial issue that can be accommodated if you’re truly getting a truly brilliant scientist, but conforming to corporate culture was also a ‘must’ for the managerial class.)

Eventually, the managerial class solved this conflict between the technical folks and managers in interviews/hiring by inviting fewer and fewer of us to interviews, and eventually pretty much eliminating us altogether. That way, they could hire the people they preferred, like themselves. But the whole point is, once your managerial class lacks true technical expertise, then they have no other criteria to use save ‘what degree do you have?’ and ‘Did you go to any ‘elite schools'”? because they lack the knowledge to ‘grill’ the candidates in depth on their actual technical expertise, like we did.

elkern

Anecdata-point: one of my fave U-Tubers is Sal Mercogliano (sp???) and his “What is Going on With Shipping” channel. He’s a former Merchant Mariner (real-world experience!) but is now chair of the…

“Department of History, Criminal Justice, and Political Science”

…at Campbell University in North Carolina.

I’m old enough that the Dept name seems really jarring. Sure, I can see how History and Political Science could be lumped together, but throwing in “Criminal Justice” says a lot about how Higher Education – and our society in general – have changed in recent decades.

“Criminal Justice” would never have been taken seriously as a University-level “field of study” during my college years (1970s-80s). I suspect that it got started in Community Colleges in the 1980s-90s, and was subsequently adopted by 4-year colleges as it gained popularity, promising “credentials” to a good career in Law Enforcement, at a time when good (Union) blue-collar jobs were disappearing.

I’d bet that it really took off in the 1990s-2000s, as thousands of young veterans came back from US wars in the Middle East looking for jobs. “Specialists” might get into commercial aircraft maintenance, etc, but for many, police work was their best option. (It’s one of the rare blue-collar careers where Unions are still strong, so wages & benefits are far better than most hourly jobs). With so many [otherwise interchangeable] applicants, Credentials (first AA, then BA) became important.

Ian Welsh

Stewart, yes, I think right now the credentialing system is causing more damage than good, by far. MBAs, economists, ivy league takeover of the press, etc… It hasn’t always been so bad, the universities were a huge part of the administrative class for the New Deal, for example. I’d say by the 60s it had become overall negative however–the mishandling of the Vietnam war, for example, by technocrats.

Ian Welsh

Carborundum: the basic numbers are available in the book. I suppose I could take some time to back-figure, but I’m inclined to trust that Randall Collins is capable of doing basic math.

Carborundum

I’ve consulted Collins and I have to say I’m not entirely sure I am any wiser as the specifics of the calculation are not specified and rely on an external source that I can’t locate.

As a quick decomp, the total population of England at the time is said to be approximately 2 million. To generate a 5% enrolment rate, assuming a 50:50 sex ratio, school-aged males would have to account for 4% of the male population [40,000 of 1,000,000], which seems a bit off to me, given medieval demographic norms. (The needed percentage would drop if a less than 50:50 sex ration is assumed.)

What *may* have happened here, given Collins’ specific wording, is that he may have interpreted school age quite narrowly: “If we can draw a parallel between Stone’s (1974:91) calculation of the ratios of the age 17 population and the total enrollment and population figures for Elizabethan England…”. I don’t think that’s workable, given what is generally said about the university educations of the period, but the math would certainly be more understandable.

mago

The great Buddhist university, Nalanda lasted from the fifth to the twelfth century in the holy land of India during which time thousands of scholars and panditas passed through its doors, including the great Shantideva.

It’s rubble now, but the light that shined in those ancient days still pervades some dark corners, even if most of us are too obscured to see it.

Jan Wiklund

What interests me is which mechanisms that governs this inflation. I don’t believe it’s demand from future employers. Governments seem to be involved, at least here in Europe. The EU has something called “the Bologna process” which seems to be intended to make a PhD of all and sundry.

For example, the institutions that take care of rehabilitation of the visually impaired can’t get reasonably educated people because the rules say that they must have a master exam, even if it’s not needed for the work. And nobody wants to spend years for getting a master exam and then get a fairly common worker salary. So there are no people in the span 20-40 years to employ. The institutions themselves haven’t asked for master exams, it’s something that has come from the EU.

And I believe private businesses aren’t more interested in paper merits than the rehabiliation institutions. I suppose the education inflation carries a salary inflation with it; the one that gets the job must after all be able to pay for the education, and they can only do that from their salary.

Nevertheless, Switzerland had succeeded to avoid it at least until the 2010s, according to Ha-Joon Chang: 23 things they don’t tell you about capitalism. They had only about 10 percent of each year class in university, the others got professional training instead. But this professional training was very good, according to a ventilation technician friend of mine.

GlassHammer

People forget that de-industrialization was a known policy across the developed world and the blue collar workforce knew about it (they were the ones getting fired) and felt betrayed.

They told their kids to get a degree for “job security” and “better” pay. This created a replication problem in the blue collar workforce (too few workers at the moment) and an over supply in college degrees. Now at the end of it all we have an over supply of white collar jobs.

Even looking back it’s hard for me to blame those blue collar parents who pushed their kids into a degree and a white collar job.

Godfree Roberts

China’s had cram schools for the Imperial Civil Service examination was opened to all in 1500 AD and still has them.

Three days of written tests (a recent hire wrote his answers in exquisite brushwork, to the delight of examiners) and three weeks of orals for top scorers.

If your IQ is below 140, you have little chance of success.

27,000 of the 1,000,000 examinees get job offers

If you take the political leadership track, you’re packed off to a remote, flyblown village on the edge of a desert. Your first promotion comes after you raise its average income 50%.

Xi did it. His father did it. Most of the Steering Committee did it.

American genius, President Donald Trump, saw the end-product and exclaimed, “People say you don’t like China. No, I love them. But their leaders are much smarter than our leaders. And we can’t sustain ourselves like that. It’s like playing the New England Patriots and Tom Brady against your high school football team.”

albrt

I found this statement about counter-elites particularly interesting: “they have the tools to fight ideologically and often the understanding of how to administer movements and other organizations.” This seems true historically but I’m not sure it is true today.

I agree that counter-elites today have the tools to start a blog or a you-tube channel to join the cacophony of voices, but as you have pointed out before nobody seems to be able to come up with an ideology that has the potential to be widely accepted right now.

Even more fundamentally, I can’t see that anybody in U.S. society has the ability to build or administer a movement under current conditions. Everybody seems to agree that existing institutions are poorly run, including the major political parties. Attempts to organize people into counter-movements seem to be even less successful. Traditional organizing skills are extremely rare, and it’s not clear traditional methods can even work when the population is directly connected to mass media, which causes isolation from their neighbors and co-workers.

So right now we’re stuck. Maybe that means we’re a good candidate for complete collapse because no counter-movement is able to emerge. But if somebody can come up with a combo-pack of ideology and organizing methods that work under current conditions, then they should be able to take over the country pretty quickly.

Willy

How quaint, quizzing applicants over technical knowledge. I remember the days of specialized teams choosing vendors, with all those papers, screen projected stats, and crunching of numbers. I’d experienced both sides of that tried-n-true old way of doing business.

Then my last manager in that business, an honest player, told me things weren’t being done like that anymore. Vendors were now being hired “because of relationships”. During a subsequent Linked-in exercise I noticed that the office carpet rut-makers were getting better jobs than those who wore out their chairs. How strange I thought, this in our new Jack Welch age of bottom-line value being everything. Neoliberalism wasn’t increasing the overall meritocracy, but apparently, causing career-loss paranoia which was supercharging the drive towards a culture of corrupt transactionalism. Meritocracy was actually being driven out.

A couple jobs before that I’d worked in a place where we were told by our MBA overlords that we’d be partnering with a German company. Our fearless PhD leader’s mother had passed unexpectedly and he was far away managing all that. So his motley crew of techs did what we could to keep the Germans busy, which we did poorly. But at least we kept them entertained (and after hours, inebriated). It was a fun week.

When fearless leader returned, he saw the lack of progress and formalized things with a formal meeting starting with formal introductions. Our side went first, describing the typical motley tech crew credentials, before Leader listed his own considerable accomplishments. I remember thinking: “Oh yeah, we got a PhD in the house.” Then it was the Germans turn. Five of them in a row had PhDs, with the sixth, the youngest, soon to earn his.

That’s when I realized we weren’t partnering with these Germans. They’d been tasked with learning everything they could about our particular innovations, so they could take all our tech back home, in exchange for their company buying our companies Chinese-mass-produced material from which to make their own version of our product with.

Our MBAs were screwing our company’s long-term future for the sake of their own short-term gains. Back at my desk the German I’d been partnered with noted my changed attitude and quickly apologized. “Back home we don’t do this to our own, at least not yet (rolled his eyes). We still consider the long-term.” His company would over time, transfer that production knowledge to China. But by then I was long gone, having been one of those gig-economy sorts.

Willy

somebody can come up with a combo-pack of ideology and organizing methods that work under current conditions

There’s always “hit bottom”, but I hope that’s more of a fallback position. I currently forsee China overtaking damned near everything the USA used to be greatest nation at. Maybe their integrity is high enough to want to sponsor organizations for change in the USA, but I’m guessing that would come at a considerable price.

And so we try to clearly and simply explain how things have been coerced to be this way, until that very rare Dear Leader we all want to follow can overcome all the PTB machinations aimed at marginalizing the message.

I do what I can (such as it is) to educate MAGA union workers (such as they are) at the actual way of things. But my cult-deprogramming technologies seem to be no match for extranational cult-maintaining technologies. And there still seem to be too many Sean O’Brein’s out there, who struggle to get their own to think for themselves, outside their little tribal boxes.

Maybe what we need are a lot more easily-understood easily-repeated slogans, geared towards the manly tribalist desperate to be cool, which are backed up by powerful facts like a glaring Luca Brasi, who’s ready to whack your ass if you disagree. Metaphorically speaking of course.

StewartM

Godfree Roberts

Your first promotion comes after you raise its average income 50%.

I wonder how much of that was fudging numbers and outright cheating?

My Chinese friends don’t describe China as that kind of meritocracy, and one of them aced the Gaokao. They describe a country that does a have a corruption and fraud problem. “Objective” measures in some ways are the most easily gamed.

Moreover from my experience, acing any test doesn’t equal intelligence. It usually means preparation and honing one’s test-taking skills. Any exam is just an artificial creation to attempt to assess knowledge, skill, and intelligence, it’s hardly a perfect indicator of actual future performance. Ever seen Einstein’s report card?

In one of my classes, I carpooled with two fellow students. We would quiz each other on potential test questions on the drive to class. A male friend was the sharpest, acing nearly every test question. A female friend would just clutch her face and say “Oooohhhh Noooo!!”. I was in the middle.

We would take the test, and the next week we got our grades. The female friend would make 98, I would have made like 94, and the male friend who aced our car quizzes would make like 86. In actual test performance, the scale flip-flopped our car quizzes.

So you see, that woman wasn’t really ‘smarter’ or ‘better’, she just knew how to take tests well. My male friend was any less smart, but he didn’t take tests as well. All three of us had reasonably successful careers.

Jan Wiklund

Aurelien, a retired British senior civil servant, has his own take on this, in connection with the calamities of the Ukraine policies of the Nato countries:

“The problem with western defence industries, for example, is not just that they chase short-term profits: it’s more complicated than that. The problem is that they have been MBA-ised like the rest of the economy, such that they are run by financiers, and so people with technical backgrounds have left and are not being replaced. Thus, even something as drastic as nationalisation wouldn’t solve the problem, because the basic capacity to produce reliable defence equipment on time no longer exists. Companies would have to be rebuilt from then ground up, which requires engineering graduates and technicians, which requires people to train them, which requires … well, you get the picture.”

https://aurelien2022.substack.com/p/ukraine-a-further-guide-for-the-perplexed