This blog is for understanding the present, making educated guesses at the future, and telling truths, usually unpleasant ones. There aren’t a lot of places like this left on the Web. Every year I fundraise to keep it going. If you’d like to help, and can afford to, please Subscribe or Donate.

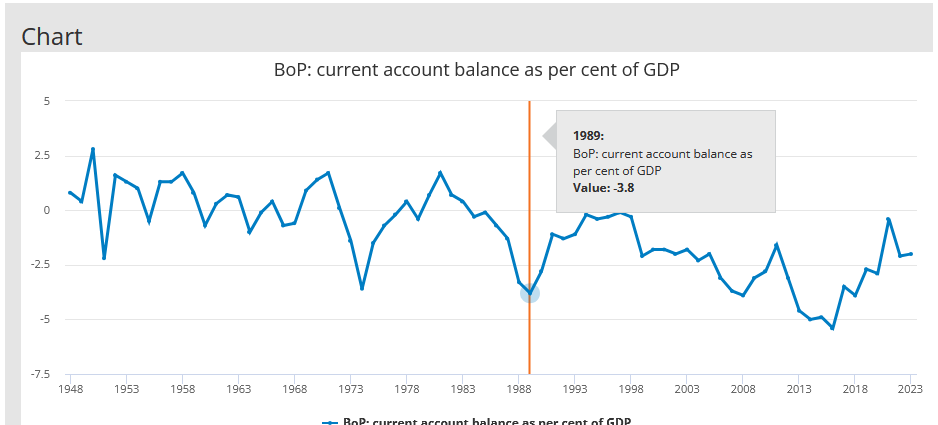

So, it’s clear from the response to my last post that some readers aren’t familiar with the effects of austerity on balance of payments and vice-versa. Balance of payments is, oversimplified, how much money is going in and out of a country.

When money goes into a domestic economy, if it is used to buy something that is imported, that effects balance of payments negatively.

If you’re selling more than you buy, which can mean services as well as good, then that helps balance of payments. It also includes financial games: so if people are sending money to the London financial center, well, that improves BoP. London’s the world’s second largest financial center, after New York.

Now here’s the thing. Britain doesn’t grow enough food to feed its population. It doesn’t have a lot of industry left. North Sea oil is depleting, to the point that Britain became a net importer of oil in 2013. (Take a look at that chart.)

When the government spends money it isn’t magically siloed from causing import demand. The government cut back on heating subsidies, for example, and limited child support payments to two children. Without that money, oil and other demand is not as high as it would be otherwise.

Indeed, nothing is really siloed. If the government spends, almost always some of that money is going to go overseas and spike imports.

Britain controls its own printing press. It can print as many pounds as it wants, but it can’t make people in other countries take the money. The more they print, the less the pound will be worth, and the more inflation there will be because the dropping pound will increase prices of imported goods.

The pound is not the world trading currency any more. It hasn’t been since WWII. It can’t print pounds the way the US can print dollars and expect everyone to just take them.

Austerity is, in many ways, cruel and stupid, but if Britain (or Canada, or Australia, or even Europe) is to print money without it causing serious economic issues and to actually reindustrialize, it has to be done intelligently, along with serious industrial and domestic economic policy. (Currently tons is printed, but siloed to the rich, which keeps general demand from exploding but destroys markets’ ability to function properly.)

Now the thing is that Britain is a high cost of living economy: food and housing are expensive. Very expensive. Workers need to be paid well to survive, and that makes Britain un-competitive against lower cost (or higher productivity) countries.

If you wanted to make Britain competitive again, you’d have to crash housing and rent, to start. You can imagine how politically fraught that is: people who have high net worth due to real estate aren’t going to like it.

Then there’s the issue of the City, the financial center. Financial center profits are HIGH. That’s a problem, because people would rather put money into finance than into industry or farming or whatever since returns are better. Finance cannibalizes the rest of the economy. So you have to weaken the city and silo it, and probably tax it a lot. That’s hard to do, because the City has a lot of power, and there’s a real issue because it does, actually, bring a lot of money in to Britain, it’s just that money doesn’t get spread around.

When you industrialize, or re-industrialize, you have to make sure that money in the domestic market buys domestic goods, doesn’t buy a lot of foreign goods, and is used primarily on industrialization: capital goods, primarily. It’s unpleasant, it means a lot of goods (imported goods) aren’t available or are very expensive. Your new industry, ideally, either serves the domestic market, or is good for export, or both.

Austerity doesn’t exist just because governments are run by stupid psychopaths (though that’s part of it), it exists because of very real constraints caused by a need to send more money out of the country than is coming in to the country. In the seventies the UK was in so much trouble it had to actually go to the IMF for help, and join the EU so Europe would help it bail out.

Now, again, there are ways around this, but they require taking on powerful interests and hurting a big chunk of the population, especially in the short to medium term (about twenty years or so.) It means, as much as possible, making do with what you can produce yourself, and when you can’t, going cheap. No foreign fresh fruit imports, except the cheapest (hope you like bananas.) Cheap phones and appliances. Etc…

It also means ending all sorts of stupid financial games: no more Private Equity. No stock buybacks. No huge stock option grants. You want money reinvested. Currency controls so money doesn’t flood out. Possibly a dual currency.

All of this is painful. But if you don’t do it, decline inevitably continues and eventually you’re back to being a third world country.

Austerity is a pressure bandage on a wound that still won’t stop bleeding. It slows down the decline, but it doesn’t heal the wound.

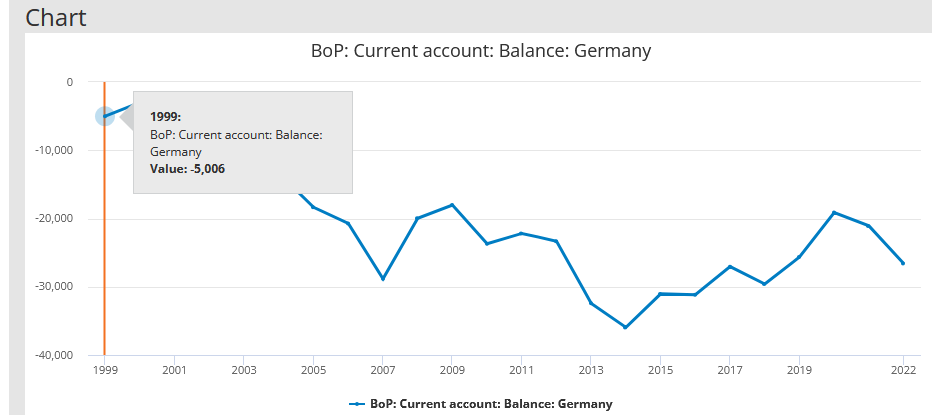

Update: Just for kicks, here’s Germany’s BOP:

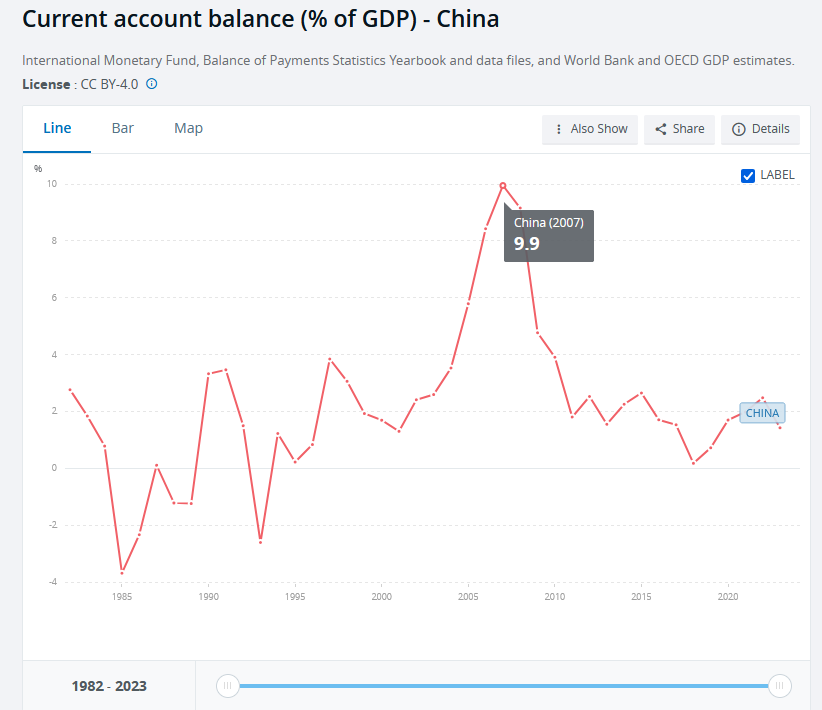

And China:

Revelo

>Currently tons is printed, but siloed to the rich, which keeps general demand from exploding but destroys markets’ ability to function properly.

Good to see you make this point, which confuse ls do many people. Any government can print infinite amounts of money and not cause inflation PROVIDED all that money ends up in the hands of misers who never spend other than to bribe legislators to change laws to further benefit the miserly rich. Feudalism/rentism with misers owning everything is a very stable system, at least in absence of external enemies that require entire population to be motivated to fight to preserve the system, and very common in human history. Misers as the top 1%, hired guns as next 9% (managers, lawyers and journa-ma-lists and inte-ma-llectuals and other priestly types, police and other whip crackers, etc), serfs as bottom 90%.

Regarding austerity, focus of austerity needs to be (and eventually will be) housing prices, because that is what is pushing up cost structure the most. Idiocy like USA health-care system is not too difficult to fix because constituency that wants to preserve this idiocy is offset by bigger constituency that wants change. But housing price decline will hit entire middle class, so huge constituency resisting change, and small constituency that benefits from change (mainly very young middle class renters planning to buy, poor also benefit from reduced rents but poor never have political power). I do not expect to see house prices fixed until there is massive economic and social turmoil and complete repudiation of current ruling class. So looking at maybe 50 years before problem finally resolved, and possibly never resolved in USA because USA can continue kicking the can down the road indefinitely due to its various economic strengths.

Purple Library Guy

The thing about austerity is it does perhaps slow certain kinds of economic damage . . . but it does so by inflicting on the people pretty much the same experience the economic damage would have inflicted on them. Not that that matters much to the rich.

And of course it also damages whatever home grown production for domestic markets remains, so that’s not ideal. After all, depressing demand will depress demand for imports . . . and also for locally produced goods.

I sometimes think ideology and class struggle is not the only reason for crappy policies, maybe often not even the most important. The thing is that once you decide government needs to intervene in any real way, like other than by broadly influencing markets by knob-twiddling interest rates or whatever, suddenly you have to start dealing with all the actual things in the economy, piece by piece, trying to fix those particular things. You may have an overarching strategy, but it is going to have to be built up of lots of individual actions–building up this thing, providing help for those people, doing education and training in the other key subjects, nationalizing that thing, creating this tariff but not that tariff.

And it’s all too hard. Modern government doesn’t want to have to think about any of that shit, it’s complicated. They’ve made slavish sycophancy the main qualification for elected office, and systematically sidelined or outright sacked the in-house expertise that used to let ministries grapple with detailed policy, and outside maybe Germany and now China, there are hardly any educational institutions that teach how to make industry, or even agriculture, work any more. It’s so much easier just to say “Oh, we’ll fiddle with interest rates, we’ll cut taxes on the rich again to unleash entrepreneurialism or whatever shit” instead of actually . . . governing.

A big part of neoliberalism is about teaching policymakers to feel good about learned helplessness. If you’re neoliberal, you can suck ass and not know jack shit about running anything, but it’s OK, it’s GOOD, because you’re not supposed to run anything . . . you can relax and leave it to the Magic of the Market.

Carborundum

Thanks for this. I think I have a better understanding of what you mean now – certainly not a perfect one, but better.

Two things do occur to me, I think potentially relevant to this issue:

1) Though it’s going largely unremarked, we’re seeing a significant amount of public sector infrastructure spending, sufficient that valuations for the big construction players government prefers are going up rapidly.

2) Recent experiences of policymakers, particularly those of a big L liberal persuasion look to me to be moving towards a belief that higher direct transfer payments are the best way to deal with a number of the challenges we’re seeing. Their experiences with child poverty (and to a lesser extent poverty among the elderly) have them positively giddy about how successful this strategy is. If they do move that way, I would guess it could cause even greater leakage than the previous norm of funnelling funding to service provision agencies.

StewartM

All of this is painful. But if you don’t do it, decline inevitably continues and eventually you’re back to being a third world country.

Well, this is *encouraging*. How would you sell it, given an electorate that thinks it has a god-given “right” for cheap gasoline so that they can drive around really big and stupid full-sized four-cab gas-guzzling pickup trucks, expensive to buy, insure, maintain, and fuel, just so they can conform to the siren songs of Wall Street advertisements?

This gets back to our previous discussion on how the media writes up economic data. I still maintain that Reagan’s tenure was just as bad if not worse than Biden’s, but as the rich were being helped while the poors were being crushed, it was written up as “Morning in America!” (and I can share my personal history as support). The fact that rents were spiking for the poors during Reagan’s term was just ignored, as was (largely) the surge in homelessness. Good for the rich = Prosperity. Reagan’s only “policy” regarding the poors at this time was that the minimum wage should be either cut or eliminated altogether.

And you know the rich would oppose the policies you suggest even more than they currently oppose Biden. So how do you sell it? Sure, FDR was able to sell the New Deal, but that was after an economic collapse, not before it. Unfortunately, even then, under Bernanke the rich learned that they could soak up all available guv’mint monies via bailouts to themselves, so there will be no more New Deals.

I fear that nearly a half century of Reaganomics has morally debased our people. Neither the child tax credit nor student debt relief polled that well, because those who don’t-have-kids and who don’t-have-student-debt can only think in the most Randian narrowly selfish of terms: “What’s in this for ME?” The fact that it promotes the common good which eventually benefits everyone does not register with them.

Failed Scholar

Ian, your post reminds me so much of a wonderful book by Chalmers Johnson, which deals extensively with Japan’s industrialization (“MITI and the Japanese Miracle”). MITI, the all powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry, essentially had almost total control of all foreign exchange in Japan until the mid 1960s. All firms foreign exchange earnings had to be converted to Yen with MITI, and likewise if you were a Japanese firm looking to import something, MITI essentially had veto power over your purchases because they could deny you foreign currency allocations if they thought it was frivolous or harmed their industrialization goals. Foreign currency that can be used to import technology or resources is something not to be wasted.

MITI also controlled the imports of all foreign industrial technology and licenses, and they would even intervene whenever they thought the terms for foreign technology imports were too encumbered for their liking (so nixing things like joint ventures with foreign firms or overly harsh royalty payments, etc).

Fascinating book anyway, I highly encourage anyone interested in the Asian State-lead Development model to read it, as Johnson covers a whole lot of ground on where MITI’s ideas and practices originated from in the first place – Meiji restoration era all the way through WW2. It covers a lot of the ground and then some on industrial policy for backwards economies that are very poor, which Japan was in the late 1800s at the beginning of their industrialization path, and this model was followed very successfully by the other ‘Asian Tiger’ economies (Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea) as well as China.

Ian Welsh

Failed Scholar,

I should read that book. Thanks. (edit: yeesh, the kindle edition is almost $40 Cdn, and softcover $47. I may cough up anyway. Seems important.)

Carborundum,

good signs, though, again, that will lead to BoP. But Canada has a ton of resources, which gives us a lot more room to maneuver than Britain has.

Purple Library Guy

Ian, might be worth checking a library–certainly a university library if you have access to one. The Vancouver Public Library doesn’t seem to have it, but my library (Simon Fraser University) does.

Randalmonte

This is however notably NOT true of reigning austerity champions Germany which is still very much industrialised and manufacturing heavy and run large trade surpluses. They are not imposing austerity because they cannot afford more imports or cannot afford to produce domestically.

Mark Pontin

Ian, you wrote: “If you wanted to make Britain competitive again, you’d have to crash housing and rent, to start. You can imagine how politically fraught that is: people who have high net worth due to real estate aren’t going to like it.”

It’s way, way beyond politically fraught and not just people with high net worth. Through the centuries, the UK has worked itself into a fascinating but uniquely screwed-up situation. As follows, if you can forgive some detailed history….

Here’s a UK Gov current briefing on Industry in the UK —

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8353/

— and if you scroll to the second chart down, there’s a ranking of Economic output by Industry as a percentage of national economic output.

Incidentally, UK Manufacturing isn’t as dead as you might assume. It’s in third place at 9.1% (And eleventh place among countries ranked by their share of global manufacturing output, though that’s not on this chart.) Retail-Wholesale is in second place at 9.9 percent.

But in first place is Real Estate, at a whopping 13.1% of UK government output! How does that even work?

Well, if you look just below the chart, it explains, “Real estate was the largest individual industry accounting for 13.1% of GVA. However, most of this is the value of “imputed rents” which is a hypothetical estimate of what owner-occupiers would pay if they rented rather than owned their homes and not output generated by the industry.”

Imputed rents as a hypothetical estimate of what owner-occupiers would pay if they rented rather than owned their homes!?! Huh? Why’s that counted as industrial output?

It’s counted because the current cause of this is that in the 1960s, when the empire and the imperial preference system disappeared, a gap opened between entrenched expectations of rising living standards and the real UK economy’s actual ability to deliver on those expectations. The gap was closed politically by [a] permitting inflationary wage claims on the part of the unions (which of course the Thatcher regime would kill) and [b] by the much more potent mechanism of capital gains for the middle class (which of course the Thatcher regime would launch into overdrive).

Still, to really understand just how real estate-derived capital gains went to the middle class in the first place, one has to go all the way back to 1777 — sorry! — when Lord North introduced a tax upon the imputed rent derived from owner-occupation to help pay for the US revolutionary war. This was following Adam Smith’s suggestion in chapter II of book 5 of THE WEALTH OF NATIONS, which noted that everyone was in a landlord and tenant relationship, receiving or paying rent, but an owner-occupier was both landlord and tenant receiving an imputed rent as landlord from him/herself as tenant, and so this should be treated as taxable income.

Consequently, a little later in 1799, when Pitt the Younger introduced his first income tax, that imputed rent got taxed; it became Schedule A under Addington’s revised income tax three years’ later. Income tax was abolished by Vansittart in 1816 and re-introduced by Peel and Goulburn in accordance with Addington’s formulation in 1841. Schedule A was for the biggest earners, but surveyors assessed every owner-occupied home and determining the imputed rent.

Now we fast forward to the 20th century. The last assessments occurred in 1935-36. In 1940 they were suspended by Wood as surveyors were overwhelmed by war damage assessment claims, as they still were in 1945 and 1950. By 1955 the 1935 valuations were way out of date, so RICS (the surveyors’ association) lobbied for Schedule A abolition (it was low margin work for them), as did the Tory party’s rank and file, who were keen to develop a Skeltonite ‘property-owning democracy’ to prevent creeping socialism.

Still, it was actually the Liberals (wishing to steal an electoral march on the Tories) who first plumped for abolition in their 1955 manifesto, followed by Labour in 1959. Finally, in 1963 Maudling abolished Schedule A, having been assured by the then-chairman of the Revenue (Johnstone) that the yield therefrom could be made up in other ways.

The shift by Labour can be explained by the success of the building society movement. In 1950 owner-occupiers were about 28% of the electorate, and by 1959 over 40%; Labour needed a share of that vote to regain office. Then in 1965 the abolition of Schedule A was compounded by the introduction of Kaldor’s capital gains tax exempting the primary place of residence. Kaldor hadn’t intended such an exemption, but Harold Wilson’s Labour had squeaked into power in 1964 with a majority of 4. The exemption was approved in committee by the chief secretary, Diamond, who noted concerns by civil servants that a person retiring from London to the provinces would face increasingly unpayable capital gains tax bill.

True. But thereby the fiscal deterrent to house price speculation was removed.

What remained was how to finance the speculation. There’d been an informal agreement between the big five retail banks to control credit. But thanks to the renaissance of the City due to the rise of the Eurocurrency markets — and particularly the Eurodollar –these credit controls were being circumvented by the new secondary banks, which were taking market share from the big five.

The upshot was the Bank of England’s Competition & Credit Control policy of 1971, which decontrolled credit. The result was the UK’s first house price bubble in 1971-73, which ended in tears with the rapid rise in bank rate in 1973 and the collapse of the secondary lenders (leading to the IMF lifeline in 1976 that you referred to and much moral hazard). Belatedly, credit was re-controlled in 1973 till 1980 (the ‘corset’).

Retention of the corset became impossible after the termination of exchange controls in 1979. The final piece in the jigsaw was the decision in 1980 by Nigel Lawson as financial secretary to allow the banks to intrude upon the residential mortgage market. In the UK that market had been the monopoly of the building societies, which could only lend what they had in deposits, whereas of course the banks could create credit ex nihilo, giving them a massive advantage.

And so ever since, real estate prices have chased credit and credit has chased prices (absent the collapse of 1988-93 when sterling shadowed the DM and during the brief pause after the GFC). Every few years in the UK people pay twice as much for half the space, people’s ability to save for retirement is compromised, and more than 80% of bank credit is directed to a non-productive asset class instead of being invested in productive capacity.

Above all, the wealth effect derived from owner occupation is spent on imported goods, deranging the UK’s current balance of payments accounts.

And this is the trap any UK government is in today. In this case, it’s Starmer’s Labour who realize that with owner occupation now at about 60% of the electorate they won’t retain office unless they buy the loyalty of a large portion of the owner-occupier class, who have an entrenched entitlement to ever-rising capital gains (even though that means ever-decreasing welfare for the young and poor). Consequently, Starmer and Co’s entire policy is based upon propitiating the economic interests of that class, just as Blair did for ‘Worcester man/woman’ in 1997.

So the UK owner-occupiers’ entitlement to ever-increasing capital gains is arguably tantamount to an article of faith. J. K. Galbraith’s comment of course comes to mind: “People of privilege will always risk their complete destruction rather than surrender any material part of their advantage. Intellectual myopia, often called stupidity, is no doubt a reason. But the privileged also feel that their privileges, however egregious they may seem to others, are a solemn, basic, God-given right. The sensitivity of the poor to injustice is a trivial thing compared with that of the rich.” However, it’s not only that.

Because the diversion of UK credit to housing starves UK industry of investment, lowering productivity and wages, it makes employed owner- occupiers that much more anxious for untaxed, unearned capital gains to offset those lower wages.

The result is that the main political parties — Tories, Labour, Lib-Dems, ReformUK –are all chasing owner-occupier votes. Indeed, the Tories would almost certainly still have had a chance in the recent election had the moron Truss not lost the confidence of owner-occupiers by inadvertently raising lending rates (thus slowing the accumulation of capital gains). The Tories are being punished for exactly the same reasons they were in 1997, and Labour are being rewarded for that reason –- and that reason alone, arguably.

By the same token, Labour will be incapable of solving the fundamental problems of the British economy which are structural, with their roots in the fiscal preference given to owner occupation created in 1963-65. Diverting credit from housing to industry would cause the bubble to deflate, impairing the banks’ main collateral (house prices).

And so the UK will continue on its rakes’ progress whomever is in power. Till it can’t, of course.

You did say you were interested in balance of payments accounting.

Ian Welsh

Germany’s BOP is, in fact, negative, and their industry is in trouble.

BOP: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/timeseries/leqk/pb

That said, they have room to maneuver, if they had enough sense to take it. The smart move would be to push for peace with Russia and get the pipelines fixed. (Much more than that, but that’d be a start.)

Ian Welsh

Lovely, Mark. Might want to elevate the housing history, if you’re willing.

I show the UK as 9th in the world, and a far 9th. Guess that shows how small the UK economy actually is.

https://www.allamericanmade.com/manufacturing-by-country/

Can’t find one that works by PPP, that would be interesting.

Anon

Sometimes, I think we forget that we made all this stuff up.

someofparts

Ian, here you go –

https://www.thriftbooks.com/browse/?b.search=MITI%20and%20the%20Japanese%20Miracle#b.s=mostPopular-desc&b.p=1&b.pp=50&b.oos&b.tile