The Great Depression was cause by a demand problem: there wasn’t enough demand for goods, prices crashed and so did employment.

The policies put in place by the New Deal were almost all intended to increase demand and prices. Farm support, social security and so on. Elites were slaughtered by the great crash of 29 and the Depression. Not all supported the New Deal, in fact many don’t, FDR bragged they hated him. But obviously FDR had elite support.

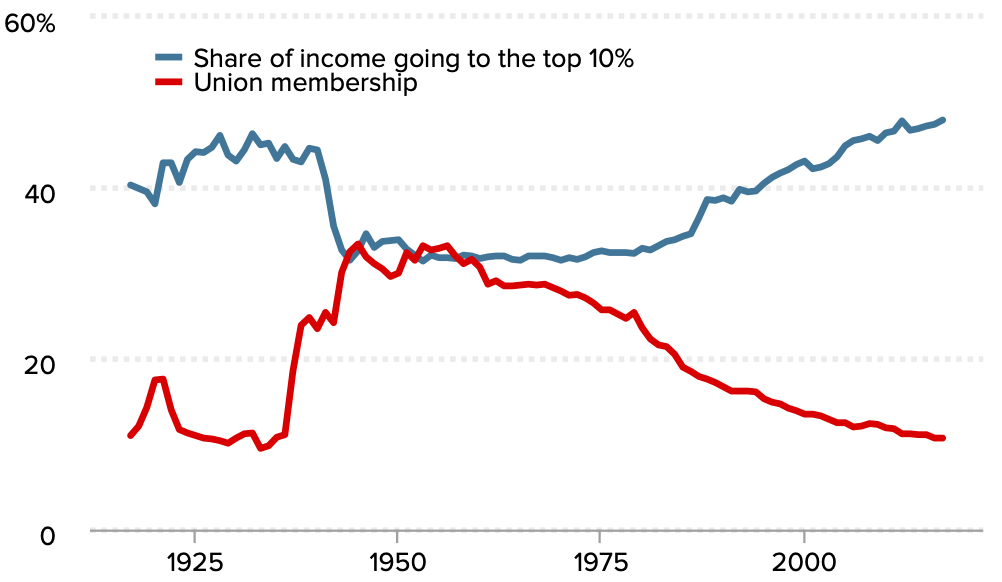

This chart shows what happened:

I think that’s pretty clear. Union membership soars with new Deal, plateaus, then slowly declines. Elites after WWII were not nearly as scared, the economy was good, and Truman’s veto was over-ridden when an anti-union bill which made foreman inelligible for union support passed.

Over time public support for unions also declined. What happens is that those who remembered the depression and the time before it age out: we’re not talking GI, we’re talking Lost and older generations. The GI saw the depression, but they didn’t experience the roaring 20s. They didn’t get what life was like before all the wage, price and demand supports put in place by FDR.

But the mid 70s these people are out of power: not only was there a wave of deaths, but in the 70s there was a movement to replace them in Congress. The incomers wanted process fairness, not outcome fairness and they replaced the old timers. (Matt Stoller has written about this extensively.)

Soon afterwards the neoliberal era dawned, and its intention was to make the rich richer and everyone else poorer: to crush wages, ostensibly to deal with the supply shock by stopping people from consuming goods and services which required petroleum products. Children of the 70s supply shocks, they were terrified of inflation and figured that rich people don’t produce inflation which matters. (This is before the era of private jets.)

In general all successful political action requires some part of the elite to support it. It doesn’t have to be all, it doesn’t even have to be a majority (it wasn’t during the New Deal) but it must exist. Popular support is a power source, but it requires transmission and an engine to turn it into action.

Close to the end of the annual fundraiser, which has been weaker than normal despite increased traffic. Given how much I write about the economy, I understand, but if you can afford it and value my writing, I’d appreciate it if you subscribe or donate.

bruce wilder

People who watch the movie Its a Wonderful Life and recognize Mr. Potter as genuinely representative of real actors in political and economic life as opposed to those who just see an entertaining cartoon or fairy tale.

bruce wilder

I think a really good historical narrative of the Great Depression — one that fully explains analytically what happened in the U.S. and world economy in the 1920s — has yet to be written. That economists ignore economic history is regarded in some circles as a scholarly shortcoming, but I will say that the incapacity of economists to do economic history — to explain the most dramatic and important economic event of the 20th century not to mention any part of the 300 year history of the industrial revolutions — is an indictment of economic theory for criminal faults.

The explanation you offer — a shortfall of (aggregate) Demand — is kind of the Keynesian explanation. I have read Keynes’ General Theory several times and all I can say is that it is 1.) a Great Book because it shows a great intellect wrestling with an important problem in its field of expertise, but 2.) Keynes’ argument is a hopeless mess. If you want to study how to think, it is instructive. If you want to understand the economy, probably not so much.

Karl Polyani waves his hands a lot, but he has the essence of the problem posed by the advance of a money economy where money is institutional infrastructure run for the benefit of extremely wealthy people.

Exactly what set up the rapidly developing economy of the U.S. in the 1920s — caught up in heady experience of the maturing of Second Industrial Revolution while a large part of the country, still agricultural in orientation, was confronting the implications of a collapse of agricultural prices — is way beyond the scope of a comment. There were major contradictions locked into the development path of agriculture and of electricity generation and energy and rail transportation that created coordination problems the so-called market economy was ill-equipped to manage and made debt structures challenging to re-negotiate, so to speak. That’s what Keynes sensed but could not articulate adequately, I think. In any case, the combination of those coordination problems with an international monetary system founded on a gold exchange standard triggered a massive, sustained deflation in the U.S. that destroyed the banking system and drained the U.S. economy of “effective demand”. And even while it was happening, month after month, few seemed able to understand even dimly what was happening, what the mechanisms were. The remedies proposed and implemented were based in large part on faith in moral imperatives and slogans bordering on hope in magic incantations and rituals. People were afraid, deeply afraid, but that didn’t make them any smarter.

The Great Depression is what happened as a consequence of the unmanaged growth of U.S. economic power at the time of its first maturing into a kind of early adulthood (a metaphor obviously). We living now may get to experience its unmanaged collapse into senescence. Lucky us.

Oakchair

The Great Depression was cause by a demand problem:

—–

The book “Monopoly Capitalism” published in 1966 by Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy discusses how this problem is a result of our monopoly capitalist system and never went away. Into the 60’s unemployment + military employment was equivalent to unemployment in the Depression.

Through emergent properties, consolidation, and collusion prices no longer follow any sort of demand curve.

The book details how planned obsolesces of products and imperialistic forever wars are a result of monopoly capitalism trying to solve the demand shortage in a way that is supported by the ruling oligarchy.

Another feature is mass spending on marketing/advertising as the monopoly system no longer competes using prices and quality, but competes based on psychological manipulation.

Indirect marketing costs even in the 50’s-60’s were a large part of the cost of goods. New more expensive products are functionally little different from the old ones (worse now a days), but they have a new aesthetic. They cost more because manufactures spend so much money trying to appeal to a population who has been in the clutches of advertising since birth.

In the book cars were used as an example but a modern example would be Apple, Microsoft et al put out a new user interface every few years. The quality and function of the product is the same if not worse, but the new interface tricks consumers into believing they’re buying something new and improved.

Some long term outcomes of this system mentioned are increased social problems, worse emotional and mental states, a shallow society obsessed with appearances, and disproven ideas get discarded less and less because the marketing apparatus has fetishized them and turned them into an status identify.

The book was published in 1966 and it’s revealing how even then people could see quite clearly where our society was heading.

PDF of “Monopoly capitalism” at the link.

http://digamo.free.fr/barans66.pdf

Net Neutrality

Are you saying unionizing and organizing needs to lead to taking political office to really matter?

Revelo

Miser oligarchy is the natural condition of densely populated societies. Top 1% own everything and there is no inflation because elite are misers (by virtue of natural selection over several generations), so any additional money printing or gold production just gets added to the treasure rooms. Next 9% are managers, lawyers, hack intellectuals, hack journalists, other hack priests/propagandists, security forces and other whip crackers. Middle class is kept in line through insecure employment and terror of falling to bottom class. Bottom 90% are immiserated workers. Stagnant oligarchy takes the form of feudalism (land is source of wealth) prior to industrialization and rentier capitalism post industrialization. Stagnant oligarchy is very stable, until an existential threat requires the elite to get the enthusiast support of the bottom 90%, versus mere forced obedience, which requires sharing wealth.

Note that robots reduce advantage of huge work forces, so 1:9:90 ratio might change to 50:20:30 or whatever. But it won’t be because middle and bottom classes get lifted but rather because many in the middle and bottom classes are exterminated (by the next pandemic) while the elite undergo normal population growth.

Great Depression was an existential threat that required sharing by the elite because weapons owned by the masses (rifles) were equal to weapons owned by elite security forces. Elite controlled security forces additionally had warships, artillery and aircraft (though not helicopters) but these would have been useless in a guerrilla war fought largely in big cities close to rugged forests of the Appalachian mountains.

Rifles are no longer the dominant weapon they were in the 1930’s (and throughout the 19th century, which is why white USA workers were never as impoverished as their counterparts in Britain) because of helicopter gunships, infrared goggles, drones, surveillance and intelligence technology, etc. Plus, even though USA civilians are well armed, much of this advantage is neutered by the extraordinarily effective USA state propaganda machinery. Internal resistance thus unlikely to pose a serious existential threat to USA elite. Security forces would simply stage horrifying false flag operations to justify limits on private ownership of guns, then use honeypot social media to locate nodes of resistance. Reduced need for workforce due to robots means strongholds of resistance could be eliminated by simply killing/starving the whole stronghold, including destroying whole cities as in Ukraine/Gaza.

One unexpected ray of hope is that USA elite is so hell bent on maintaining world hegemony that it may create precisely the sort of external existential threat that can only be dealt with by enlisting support of the masses, meaning sharing wealth. I’m thinking asymmetric warfare by Islamic forces and Russia, and perhaps Latin American resistance in the future: drone attacks on USA infrastructure, biological warfare, propaganda that offsets USA state propaganda, etc.

tl;dr: Learn to like the idea of never ending world war at a low simmer. Alternative might be worse.

Jan Wiklund

The article focuses exclusively on ideology, which I think is misplaced. There were solid facts behind.

As Alfred Chandler has shown (Scale and scope, 1994), there was a real crisis in the 60s-70s. The industrial giants had become so efficient that they could produce more than people could, and would, buy. Earlier, they had been able to finance their investments with earned profits. Now, they couldn’t because they couldn’t sell enough. The had to turn to the finance markets, i.e. the rentiers.

And rentiers are not interested in production, probably they don’t understand it. They wanted returns on their money, immediately. So big business had to change its priorities – from production to finance manipulations – outsourcing, buybacks, etc etc.

That is the secret behind labours declining power. Workers were not needed any longer. Neither as workers nor as customers. So they had nothing to offer.

Purple Library Guy

I’d just like to note that a crisis caused by insufficient demand is really the flip side of Marx’s “crisis of overproduction”. Capitalism wants to produce more and sell more, but it also wants to minimize what it pays workers so as to maximize profits. At some point if it succeeds on both fronts, nobody can afford to buy enough of the stuff.

Purple Library Guy

As to whether unions can ever gain strong success without noticeable elite support, I don’t think this article really establishes that. Maybe it’s true, maybe it isn’t. One example (the Great Depression in the US context) does not make a trend, let alone a general rule. How much elite support was there for 19th century unionization in Britain, and the Chartist movement? I don’t remember hearing of much.

I’m sure elite support makes it EASIER, and maybe in societies with some correlations of forces it’s actually necessary. But I’m not at all convinced it always is. Elite control has limits–it can be very strong when things are going pretty smoothly (and rebellion from the base is also going to be quite limited at such times). But when stratification and instability rise along with increases in the venality of elites, when elite greed causes the economic system to begin breaking down, that breakdown includes methods of elite control. If nothing is getting repaired in working class neighbourhoods, that includes billboards and cell phone towers. If people can’t afford internet access or phones, that means they can’t afford propaganda. In extreme cases, sometimes even the security forces decide the situation is bullshit and refuse to crack down on their relatives.

The recent US election saw a breakdown in the effectiveness of centrist PR . . . people just stopped listening. Even the fascist stuff wasn’t working really well, Trump got 3 million less votes than in the previous election–it’s just that Harris got 15 million less compared to Biden. So the effectiveness of fascist rhetoric and its matrix of communications arguably eroded slightly, but the effectiveness of business-as-usual rhetoric and communications plummeted . . . arguably the bigger story is that ALL methods of elite manipulation saw reductions in effectiveness. It is possible that if the US economy continues to decline, stratify, and operate in counterproductive ways (e.g. private equity funds looting and killing hospitals), elite capacity to control the population will decline to the point that a strong union movement would be able to succeed even without elite support. Of course such a movement is largely hypothetical . . .

mago

Never ending war at a low simmer will get blown out of the water through environmental and economic degradation.

Unsustainable resources.

Maybe just blow it up, build it over again.

Seems to be a trend.