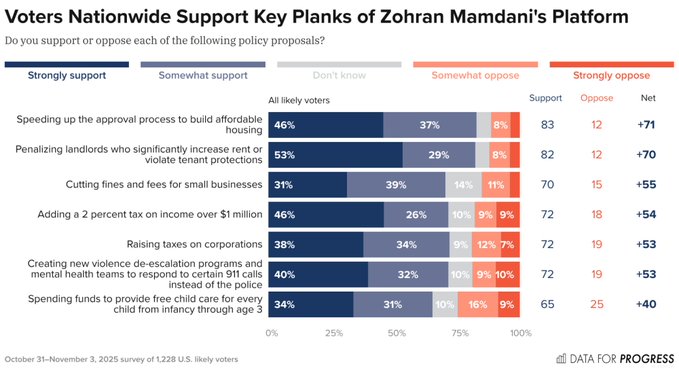

As everyone’s probably aware, Mamdani, a brown muslim social-democrat who has promised, among other things, to open city grocery stories, make transit free, a rent freeze on stabilized units (about 40% of New York’s apartments), universal free child care and to build 200K new apartments. He’ll pay for it with tax hikes on rich New Yorkers and corporations.

As everyone’s probably aware, Mamdani, a brown muslim social-democrat who has promised, among other things, to open city grocery stories, make transit free, a rent freeze on stabilized units (about 40% of New York’s apartments), universal free child care and to build 200K new apartments. He’ll pay for it with tax hikes on rich New Yorkers and corporations.

(Read Mamdani’s Victory Speech. Powerful stuff.)

Mamdani’s extraordinarily charismatic, with an upbeat optimistic style and rarely shies from fights (though he has backed down on Palestine.) He’s a good candidate.

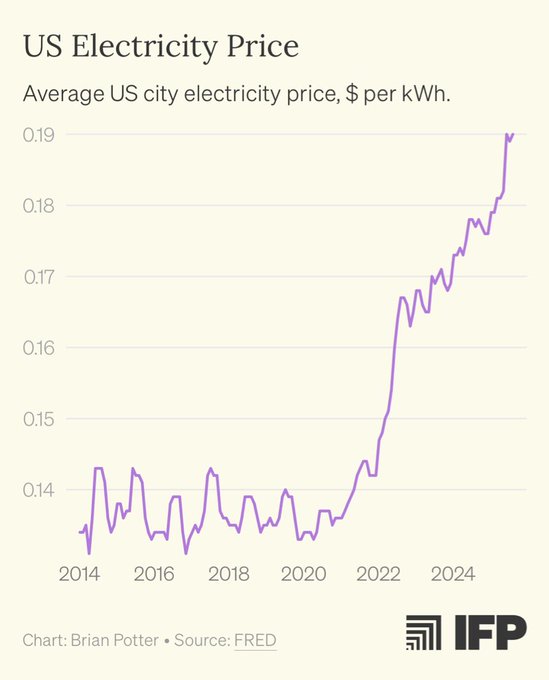

But he won because he was laser focused on the affordability crisis: food, housing, transit and child care. For many years now I have said that voters in most Western countries want real change, and they will vote for anyone who seems to not be like a status quo politician and for any promise to overturn the status quo. Like a wolf in a leg trap, they’re so desperate to escape from a future of eternally lowering expectations, one in which they can’t afford a home, can’t afford kids, can’t afford holidays, and are even told not to buy expensive coffees.

Trump doesn’t come across as an establishment politician, so many people voted for him. Corbyn’s wave was based on this. Brexit was based on “ever since we’ve been in the EU things have gotten worse for ordinary people in Britain.” Yes, the EU wasn’t the reason (though it is a pile of garbage, it’s a less rancid pile than British pols who wanted out of it), but that didn’t matter. “Get ground into the dirt slower, peons” doesn’t sell any more.

So people will vote for Britain’s Reform, or Canada’s Conservatives, or LaPen, or Germany’s AfD. Nasty piece of shit fascists, all of them. But they act differently from establishment politicians, and people will vote for that, even if their likely policy are vile and stupid and cruel.

It isn’t just Mamdani who won yesterday, ever major race outside Texas when Democrat, and all the Democrats ran on affordability issues.

Now one of the tropes is that young men have gone right wing in most countries. There’s some truth to it, but less than it appears:

NBCNews exit polling on young men (18-29) in VA, NJ and NYC VA: Spanberger +14 NJ: Sherrill: +10 NYC: Mamdani +40

If young men were solidly right wing, this wouldn’t have happened. What they want is change. They’ll take right wing change if that’s all that’s on offer, but just as Bernie was projected to beat Trump in a direct competition, they’ll take left wing change preferentially, because left wingers offer hope (free stuff) that right wingers just refuse to match. The right wing offer is “we’ll kneecap your peer competitors: women and immigrants, so you do better.” The left wing offer is “we’ll help everyone and we’ll actually give you shit and actually stop prices from increasing.”

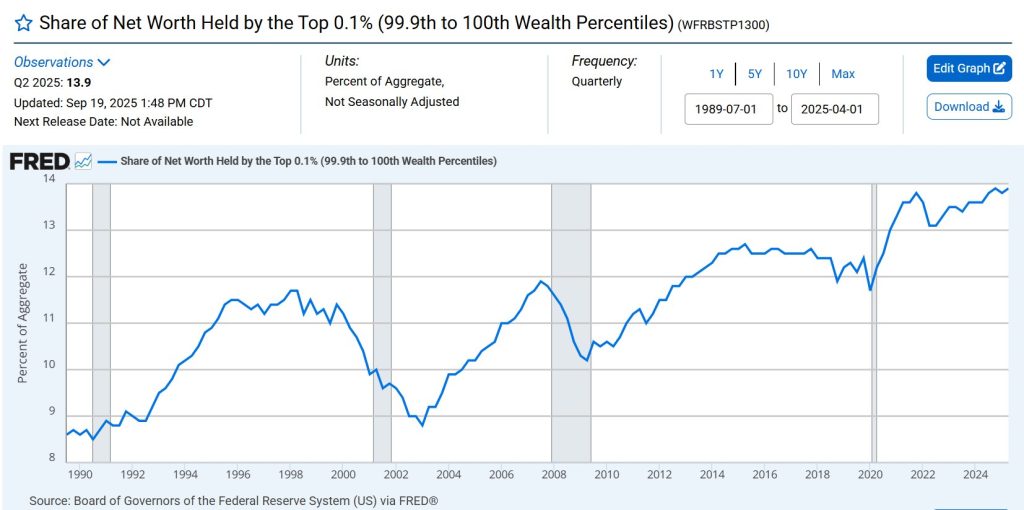

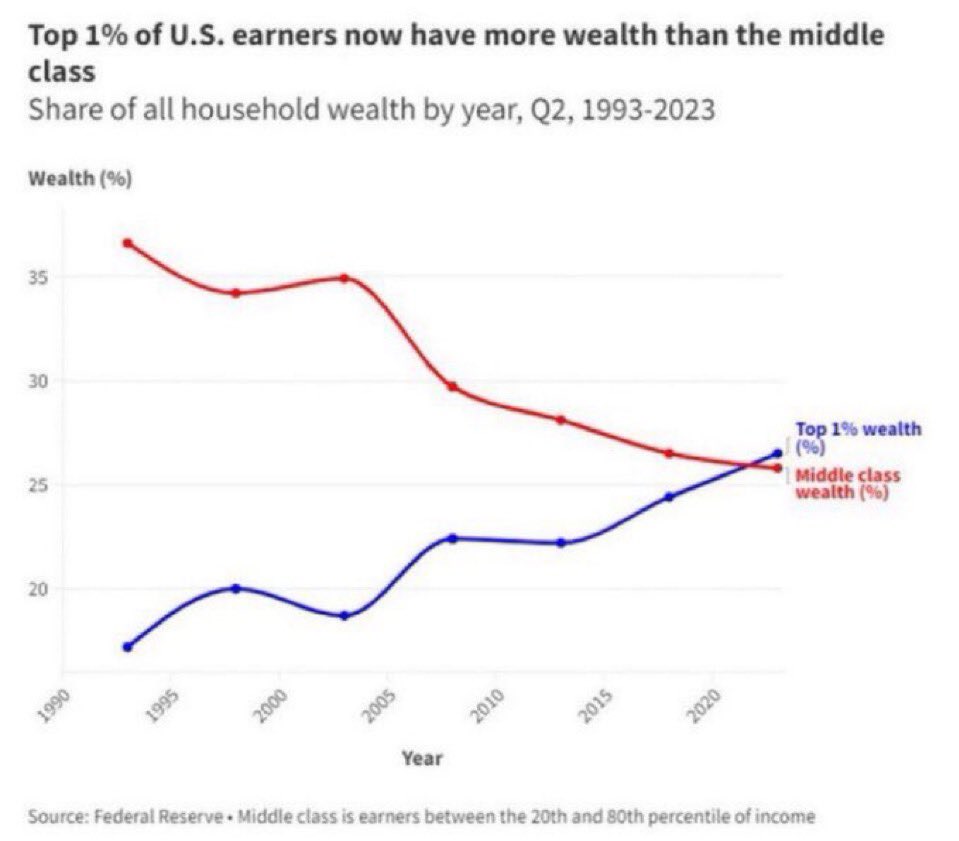

The left wing offer is better just on straight up self-interest. And a lot of people hate the rich far more than they hate immigrants, so the “and we’ll soak the rich” left-wing offer goes over well. It’s also more realistic because it is the rich who actually destroyed America’s prosperity, and to the extent immigrants contributed, it’s because the rich used them force wages lower: the classic strategy of “pit one half of the working class against the other half.”

Alright, so that’s why Mamdani won. But what now?

New York city is a “creature of the state”. Kathy Hochui, the governor, and the NY State legislature have veto power over essentially everything Mamdani wants to do. Hochui endorsed Mamdani, BUT while she agrees with his policies, there’s one big exception: she doesn’t want to increase taxes on the rich and corporations, and she effectively has a veto.

So what’s likely to happen is that she kneecaps Mamdani by making it so he can’t get the money to do all that he wants to. (Saying you agree with Mamdani while making sure he can’t deliver isn’t actually agreement. It’s an attempt to pander to the left while still getting rich by actually protecting the oligarchy.)

Trump has said that he will cut funding to New York and we can expect the standard ICE and border patrol invasion.

Mamdani’s going to face to tidal wave of elite opposition to what he wants to do. If he’s to be successful, and the first exemplar of a new wave of left wing politicians in America (America’s only chance of a decent future) he has to figure out a way to still deliver on enough promises (rent freezes, for example) so that New Yorker’s feel better off AND he needs to frame his losses as because of enemy action which can be defeated in the future by electing his allies as New York state governor, to the state legislature, and to federal offices. He needs to become the linchpin of a larger movement. He cannot be seen as a failure, he must appear as a fighter who has some victories and part of a movement which can win overall.

All of this is possible. People hate, hate, hate the elites in America. Attacking landlords, health insurance executives and politicians who cover for them and want them to get even richer is popular. Taking action against them in whatever ways are possible is adored. Mamdani is lucky in this: his enemies are loathsome parasites who aren’t satisfied being the richest rich the world has ever seen, they want MORE and they want to take it from everyone else.

Mamdani knows a fight is unavoidable, so he’s squaring up and framing the fight as a mass fight against a corrupt bully. (From his victory speech.)

So Donald Trump, since I know you’re watching, I have four words for you. Turn the volume up! We will hold bad landlords to account because the Donald Trumps of our city have grown far too comfortable taking advantage of their tenants. We will put an end to the culture of corruption that has allowed billionaires like Trump to evade taxation and exploit tax breaks. We will stand alongside unions and expand labor protections because we know, just as Donald Trump does, that when working people have ironclad rights, the bosses who seek to extort them become very small indeed.

New York will remain a city of immigrants, a city built by immigrants, powered by immigrants, and as of tonight, led by an immigrant. So hear me, President Trump, when I say this. To get to any of us, you will have to get through all of us.

What Mamdani represents is America’s last hope. If the movement he exemplifies loses, America’s future is to slowly un-develop, becoming more akin to Brazil or India than to developed nations. Vast numbers of homeless, desperate workers, extended new slums and people absolutely desperate for food, healthcare and housing. In this he is similar to Corbyn: the last chance for America to turn it around before the shit hits the fan. If this movement fails, America fails. It may be able to get back up again, sure, but it will be far harder to do in twenty years than in three or seven years.

While it is in everyone’s interest, including over 90% of Americans for the American Empire to end, having America become a failed state, its likely prospect if current trends continue, will be horrific.

Avoiding that is, to a remarkable degree, on one Muslim social democrat’s shoulders.

The annual fundraiser ends this week. We’re less than $500 out from making our goal. If you value the site and can afford it, please give or subscribe. I’m incredibly grateful to all who have given and to all subscribers.

As everyone’s probably aware, Mamdani, a brown muslim social-democrat who has promised, among other things, to open city grocery stories, make transit free, a rent freeze on stabilized units (about 40% of New York’s apartments), universal free child care and to build 200K new apartments. He’ll pay for it with tax hikes on rich New Yorkers and corporations.

As everyone’s probably aware, Mamdani, a brown muslim social-democrat who has promised, among other things, to open city grocery stories, make transit free, a rent freeze on stabilized units (about 40% of New York’s apartments), universal free child care and to build 200K new apartments. He’ll pay for it with tax hikes on rich New Yorkers and corporations. This is, again, because Chinese models are at least 90% cheaper to run, and mostly open source. Only a complete and utter moron would run their business using proprietary models where OpenAI or Anthropic can jack up the price any time they want or depreciate the model you actually needed. Even US startups agree, 70 to 80% of them are using Chinese open models.

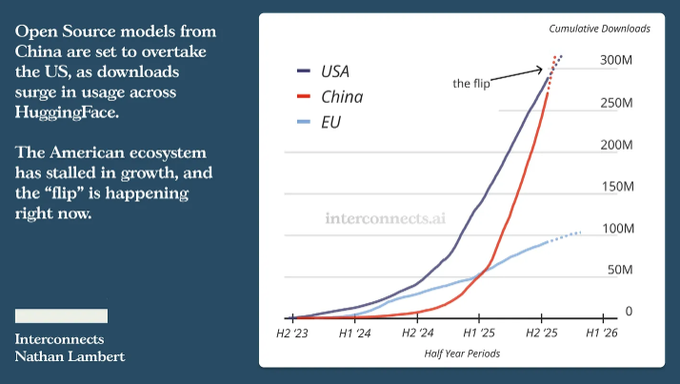

This is, again, because Chinese models are at least 90% cheaper to run, and mostly open source. Only a complete and utter moron would run their business using proprietary models where OpenAI or Anthropic can jack up the price any time they want or depreciate the model you actually needed. Even US startups agree, 70 to 80% of them are using Chinese open models. These numbers are astounding:

These numbers are astounding: