Sanders-021507-18335- 0004

This post by Pachacutec seems worth revisiting (originally published Feb 16, 2016)– Ian

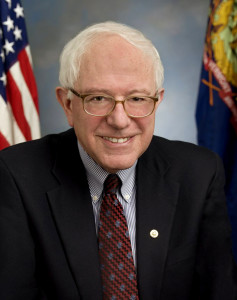

Bernie Sanders is taking a lot of heat for making promises everyone agrees can’t be achieved in today’s Washington. However, Sanders is not just smoking free-love-sixties-dope when he talks about universal health care, free college tuition, stopping deportations, and drastically cutting the prison population.

I used to teach negotiation to MBA students and lawyers seeking CLE credit, and have included negotiation content in executive coaching and other consulting work I do. One of the things I’ve sometimes taught was how to use audience effects to gain leverage in negotiations. The best story I know to illustrate this comes from Gandhi, from his autobiography.

Gandhi Rides First Class

Gandhi’s early years as an activist led him to South Africa, where he advocated as a lawyer for the rights of Indians there. One discriminatory law required “coolie” Indians to ride third class on trains. Soon after arriving in South Africa, Gandhi himself had been thrown off a train for seating himself in first class.

Looking for a way to challenge the law, he dressed flawlessly and purchased a first class ticket face to face from an agent who turned out to be a sympathetic Hollander, not a Transvaaler. Boarding the train, Gandhi knew the conductor would try to throw him off, so he very consciously looked for and found a compartment where an English, upper class gentleman was seated, with no white South Africans around. He politely greeted his compartment mate and settled into his seat for the trip.

Sure enough, when the conductor came, he immediately told Gandhi to leave. Gandhi presented his ticket, and the conductor told him it didn’t matter, no coolies in first class. The law was on his side. But the English passenger intervened, “What do you mean troubling this gentleman? Don’t you see he has a first class ticket? I don’t mind in the least his traveling with me.” He turned to Gandhi and said, “You should make yourself comfortable where you are.”

The conductor backed down. “If you want to ride with a coolie, what do I care?”

And that, my friends, illustrates the strategic use of creating an audience effect to gain leverage in a negotiated conflict. The tactic can be applied in any negotiated conflict where an outside stakeholder party can be made aware of the conflict and subsequently influence its outcome.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing, and want more of it, please consider donating.)

It’s the Conflict, Stupid

A couple of weeks ago, members of the neoliberal wonkosphere and others in the pundit class tut-tutted, fretted, and wearily explained to Sanders’ band of childish fools and hippies that his “theory of change” was wrong. Well, not merely wrong, but deceptive, deceitful, maybe even dangerous. False hopes, stakes are too high, and all that. This was Clinton campaign, and, more to the point, political establishment ideology pushback. When Ezra Klein starts voxsplaining how to catalyze a genuine social, cultural, and political movement, you know you’ve entered the land of unfettered bullshit.

Bernie Sanders, like Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter before him, wants to use mass appeal audience effects to renegotiate the country’s political and economic contract. The strategy, writ small in Gandhi’s train ride tale, is perfectly applicable–and has proven successful through history–in bringing about successful, peaceful, radical change.

These movements operate by forcing conflict out into the open, on favorable terms and on favorable ground. Make the malignancy of power show its face in daylight. Gandhi and the salt march. MLK and the Selma to Montgomery marches. FDR picking fights and catalyzing popular support throughout the New Deal era, starting with the first 100 days. OWS changed American language and political consciousness by cementing the frame of the 1% into the lexicon. BLM reminded America who it has been and still is on the streets of Ferguson.

One FDR snippet is instructive to consider in light all these discussions–and dismissals–of Sanders’ “theory of change.” As FDR watched progressive legislation be struck down by a majority conservative court, he famously proposed legislation that would have allowed him to add another justice. He failed, but:

In one sense, however, he succeeded: Justice Owen Roberts switched positions and began voting to uphold New Deal measures, effectively creating a liberal majority in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish and National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, thus departing from the Lochner v. New York era and giving the government more power in questions of economic policies. Journalists called this change “the switch in time that saved nine.”

This was a constitutional overreach by FDR, and it caused him political damage, but forcing the conflict created pressure on the Court, making its actions highly visible to the mass of people who wanted change, who voted for change, but did not always see or understand how the elite establishment acts to thwart change.

Your Mistakes are My Ladder

The paths to change for all of these movements are neither linear nor predictable. By nature, they act like guerilla movements. They force conflict and force an entrenched enemy into the open. Then, once exposed and vulnerable, the guerilla tactic is to attack opportunistically on strategically favorable ground. In peaceful social movements, “winning” means winning the hearts and minds of the majority of the society’s stakeholders to the point where they actively choose sides. First make them witnesses, then convert them into participants in the conflict. That’s exactly what Gandhi did with the Englishman in the first class compartment.

This is why calls from pundits and Camp Clinton for Bernie to lay out the fifteen point plan of how he gets from here to there are, at best, naïve. The social revolution playbook requires creating cycles of conflict and contrast, taking opportunistic advantage of your opponent’s mistakes. No one can predict with certainty where and how those opportunities will arise, though you can choose where to poke. If the Clinton campaign wants to know how Bernie can run that playbook in action, it need only review its own performance campaigning against him.

Does Sanders Have a Plan?

So, is Bernie Sanders the underpants gnome of political change? Is his theory: “1) Call for revolution; 2) ?????; 3) Profit!”? Or does he have something else–some other historical precedents–in mind? Everything I hear and see from the Sanders campaign suggests the latter.

Take a look at this ad from Sanders:

To me, this ad says that Sanders understands very clearly what kind of coalition and movement he needs to ignite to accomplish the vision he’s putting out in his campaign. It’s an aspirational vision, sure. And neither he nor any movement he helps create can or will accomplish all of it, just as FDR was unable to accomplish all he set out to achieve. Still, accomplishing as much as FDR did, relatively speaking, would be pretty damn good. Democrats used to say they liked that sort of thing.

Or how about this ad, where Sanders is introduced by Erica Garner explicitly as a “protestor,” invoking the lineage of MLK:

Yes, I’d say Sanders has a very clear, and historically grounded “theory of change.” What those who question it’s validity are really saying is either: 1) they lack imagination and can’t’ see beyond the status quo; 2) they lack knowledge of history, including American history, or; 3) they understand Sanders’ “theory of change” very well and want to choke it in the crib as quickly as they can.

They may succeed. Elites may beat Sanders himself but they will not beat the movement he’s invigorating but did not create. However, saying Sanders may fail is not the same as saying he doesn’t know what he’s doing, or that what he’s setting out to accomplish is impossible.

Because, if history shows us anything, it is, indeed, possible.

Hi. I’m the blogger/artist formerly known as Pachacutec. If you are old enough to remember me as a lefty blogger, you’ve been on this internet thing too long. But I digress.

Hi. I’m the blogger/artist formerly known as Pachacutec. If you are old enough to remember me as a lefty blogger, you’ve been on this internet thing too long. But I digress.