Back in 2016 I wrote a piece called “Seven Rules For Running a Real Left Wing Government.” It proved to be one of my most popular pieces, particularly loved by activists. Since then I’ve often been asked for an more and I’ve finally written a partial update and companion piece.

Back in 2016 I wrote a piece called “Seven Rules For Running a Real Left Wing Government.” It proved to be one of my most popular pieces, particularly loved by activists. Since then I’ve often been asked for an more and I’ve finally written a partial update and companion piece.

The Sixth Rule was “Reduce Your Vulnerability to the World Trade System.”

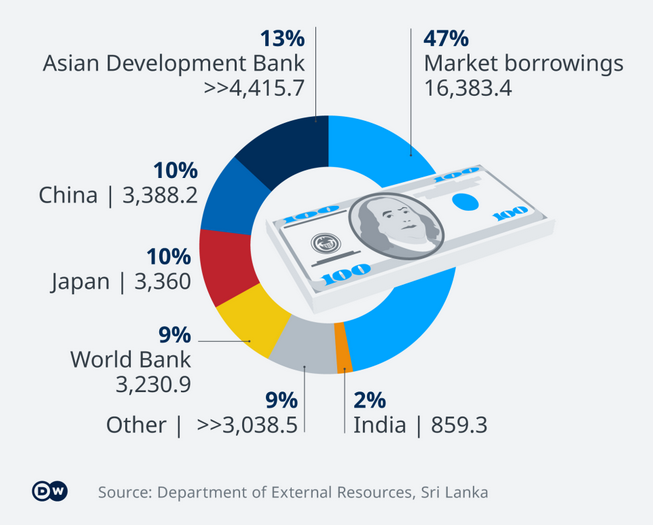

This rule is still true, but how it is applied has changed — you can use a relationship with China to, over time, reduce your dependence on the old system which required you to stay poor and dependent..

Back in 2016 China was massively important, but the rules of the system were still all-powerfully American. Those rules are breaking down now and your government can take advantage of that. Though the title of this piece is about China, much applies to bilateral relationships with other countries. China’s the biggest and most advanced and most useful right now, however.

What working with China can do for you.

- Movement up the industrialization chain;

- Modernization

- one time infrastructure

- cheap loans

- Training and teching-up your scientists, engineers and designers.

All of these benefits are available, but you have to be smart and structure your deals to give you a long term advantage, China won’t do that for you, but they are open to such deals and won’t sandbag you. To use modern bargaining speak win/win deals are available if you seek them. There are limits, of course, but those limits are far higher than they were and are under the old WTO/US system.

How The World & China Have Changed And How You Can Use Those Changes

China is now the largest trade nation in the world and caught up to the West or surpassing it in most, though not yet all, technologies.

Post-Ukraine war it has been structuring many non-dollar deals.

These deals settle outside of the banking system controlled by America and Europe and thus you are not forced into structures which automatically try to keep you from moving up the value chain without being a US satrapy (like South Korea and Japan and most of Europe) or seeking moderate economic independence. (See the original 7 Rules article for how the old system works.)

De-dollarization and a nascent non-Western banking system make it possible to break the stranglehold the old international trade and finance regime put on left wing governments.

To take advantage of this opportunity you need to understand China’s domestic issues:

- China has far more construction and development capacity than it needs. It has built most of the buildings, roads, ports, hospitals, schools, power plants and so on it requires. China could get rid of those jobs and cut the industry in half OR it could use it overseas and not throw a pile of people out of work and destroy half an industry. This means, among other things, that China is willing to put up infrastructure for very low prices in order to keep the people employed.

- China has a vast need for resources: food, fuel, minerals and so on. If you’ve got it, odds are they need it and they want long term secure deals.

- China is moving up the manufacturing value chain and moving into services. In many cases the Chinese government has forced industries to shut down low value manufacturing plants that are still profitable. They want the lower chain industry out of their country, and over time what counts as “lower” moves further up the chain.

What all this means is that China is willing to build your country what it wants for cheap in exchange for deals for your resources and, more importantly, to relocate industry to your country.

You have to take advantage of this in the right ways, or it is just another trap, but it’s still a big opportunity because the US offered this deal to only a few nations and required satrapy status in return. Think South Korea and Japan and Taiwan.

This isn’t to say that China doesn’t have some non-negotiable requirements if you want to be cut in on the good deals, however, they’re just less onerous than the old US and European deals were. Let’s discuss that next.

China’s Non Negotiable Requirements

These are simple. You will not recognize Taiwan and will stay out of the Taiwan/Mainland dispute. You will stay out of anything relating to Tibet and that will most likely include not hosting the Dalai Lama at the senior government level. If you are not in the South China Sea, you’ll stay out of that dispute.

These aren’t particularly onerous, though you may find they stick in the craw slightly. Still, it’s a lot less than what the US and Europe require.

What You’ll Lose By Aligning With China

Simply, good treatment from Europe and the US. That means reliable and fair access to the western financial system, the ability to buy Western military gear and expect to get parts and ammo when you actually need it, and to a lesser extent, access to western goods and services.

The financial aspect is the most important, but will become less and less important. The whole point is bilateral or multilateral deals outside of the Western financial system anyway, and it’s that financial system which has been primarily responsible for keeping the global South down for the last 70 years.

The military aspect is negligible at this point. It’s clear that the West’s military production system is sclerotic and can’t keep up with major demand spikes: we’ve seen that in the Ukraine where they can’t even keep Ukraine supplied with enough dumb artillery shells. You’re better off getting your military supplies from China, Russia and Iran. There isn’t even much of a quality gap and in some areas, like missiles, you’ll receive better.

As for goods and services, increasingly, outside of pharmaceuticals (which they’ll withhold from you in a crisis anyway, as Covid proved), China can supply what you need, including advanced telecom equipment and more of the production stack than the West can these days. You’re giving up very very little and in ten years it will be essentially nothing.

What Types Of Deals To Cut

There are three types of deals you want beyond the basic “we sell you stuff and then buy goods from you.” There’ll always be some of that, but the idea is to make your country more independent and more prosperous and your people better off over time. That will not happen if you just sell resources and then turn around and buy goods.

Bilateral up the chain deals.

This means “we give you resources or low chain goods and you help us move up the chain.” If you’re not already on the chain, that’ll mean starting with textiles, most likely, but you have to start somewhere.

Bilateral Cartel Deals

In these deals you agree that you’ll own a particular industry and the other country won’t compete with you. In exchange there’s an industry you won’t compete with them in and both of you will buy the others products. These deals take a lot of trust: both sides have to believe the other side won’t cut them off in the future. One “semiconductor ban” and the deal is shot, and most likely shot permanently.

China’s capable of taking over most industries if it really wants to, but there’s an opportunity cost to doing so, and they need and want good relations. In many cases these deals will be cut with a side “and if you let us keep or have this industry, and buy from us, we’ll keep selling you grain/oil/nickel/whatever.”

China wants secure deals. Give them that security and be rewarded in exchange.

One Time Infrastructure Deals

As discussed earlier, China’s the infrastructure King. If you needs roads or ports or hospitals or power plants or almost anything, they can build it fast and cheaper than anyone else and the quality is good. Maybe not Japan good, but good enough.

You’ve got to cut these deals, all of them, right, though, or you’ll wind up not receiving what you want, or in the case of infrastructure deals wind up with white elephants you can’t afford to maintain. So—

How To Structure Deals To Ensure You Benefit

The objective here is to gain local knowledge, skills and capacity. This means a few things.

No Branch Plants. You want partnership deals, 49% China, 51% you. The plants or whatever get set up in your country by their engineers and managers, in partnership with your managers and engineers. At first the foreigners take the lead, but over time they are largely phased out, the capacity becomes indigenous.

Move the parts and repairs. You don’t want to just be putting goods together from pieces made elsewhere. You want the parts moved to your country too. Lots of small companies usually support big companies. You want that network. Without that network in your country, you don’t actually have industry. With it you have the culture of industry which is required to start making your own advances, to create new products and types of work. You have the chance to get a dynamic economy which innovates.

Buy Infrastructure you can maintain. If you’re going to constantly need the Chinese to come back and fix your power infrastructure, or roads, or ports or anything else, or to constantly buy parts from them, then you haven’t really bought anything. All deals must include the necessary training for your locals to maintain the infrastructure and that most of what is needed for maintenance is made in your country.

(This is a reader supported Blog. Your subscriptions and donations make it possible for me to continue writing, and this is my annual fundraiser, which will determine how much I write next year. Please subscribe or donate if you can.)

Be very careful about large asphalt and concrete deals. Concrete and asphalt does not last and needs constant and expensive maintenance cycles. The world which supports that is going to go away as climate change and environmental collapse do their damage. Find ways to increase the lifespan of infrastructure and make it easier to maintain, ideally with as unskilled labor as possible.

If you can’t maintain it, you don’t really own it and it won’t be there when you need it.

Educational Exchange

Let’s be clear here, sending students overseas to learn from more advanced societies isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. A lot of them stay, others become compromised with values which are inappropriate to your society and much of what they learn at university isn’t all that useful in industry, unless they’re in real engineering or science and even then, less than you’d think.

Still, do some of that. It’s not a hard deal to cut, because it’s flattering to the Chinese and thanks to Chinese culture, you’ll see less of the students stay in China than used to stay in America. They’ll have to learn Mandarin, but that’s good. English will stay the lingua franca for a while, but the gravity is to Mandarin and if you’re following the advice herein, well, China’s your big trade partner.

The other exchange you want is to get your engineers and scientists and managers into partner companies in China so they can get real world experience with how industry and business works. Get them from the lowest levels where they see the factory floor to the highest levels. Have them make contacts, have them work on real products. Again, some are going to stay, but many will come home and you will benefit massively.

Most of the most important information about how products and businesses and societies work is never written down. You need your people to learn it.

So get those exchanges going. And if you need to flatter the Chinese a bit, swallow your pride and do it.

Concluding Remarks

China’s still on the rise. Countries on the rise are much more generous than countries in decline or even mature countries, economically speaking. There’s still tons of possibility and present and future surplus to share. The emphasis is on increasing the size of the pie and not fighting over a static or shrinking pie. On top of this China needs and wants friends and wants desperately to be admired. If someone wants admiration, it’s cheap and there is plenty that can be admired without hypocrisy.

Take advantage of this opportunity but remember, the goal is to increase your own country’s real prosperity by increasing your indigenous production ability and the skill and knowledge base of your own people. It is not to gain fleeting prosperity from selling resources or bottom tier products.

And remember also, this economic age, the age of heedless industry, is coming to an end. Build smart: lots of passive solar, for example. Trains and rapid transit, not expressways. Infrastructure that is easy to maintain. Goods that aren’t frequently replaced.

Learn from China but don’t be just like them, use them to create a non car-centric, non-disposable economy. If you do so, you’ll be one of the nations who prospers in the next age.

China is an opportunity to get on a ladder. Choose the right ladder.