The Syriza government in Greece just made the move of proposing a referendum on the creditors’ last (unacceptable) offer, so the Greek people can now choose a destiny from a set of unpleasant destinies to which history has brought them. From the creditor’s perspective, this pushes them into precisely the situation they have spent the last seven years (at least) avoiding at all costs–the holding of a democratic dialogue on any part of the bailout. Even their threats to remove the proposal and to cut off ELA are acts of participation in this utterly unwanted dialogue. If Syriza proceeds with this, it will have turned the “sea lion” strategy around and on its head.

The bank bailouts were a “metacrime,” a moral monstrosity by which the productive economy was sacrificed to save what should be merely the money conduit system, rather than sacrificing the finance industry to save the productive economy, and all to conceal crimes and failures inside the money conduit system. However, while the immediate precipitation of the ongoing European/Greek crisis can be attributed to this, the route to such an unstable situation is rather more complex.

Ian asked me to put together some thoughts on the matter of the attitudes, aspirations, and motives of the participants at a “cultural” and interest group level, which I believe are non-trivial drivers of this conflict. For me, at least, when people do wrong things and get themselves into bad situations, I feel it is not enough to turn them into cartoon villains; often outwardly (or “functionally”) sociopathic behaviour has an aetiology in more conventional human failings. Humans often climb up ideological trees from which it is difficult to talk them down. That doesn’t mean I necessarily take a position of pure relativism; being unable to come down from that tree is itself a moral failing.

Before I begin, a disclaimer: I’m going to be painting with a broad brush here. A few years of living in Europe have taught me how impossible it is to live without a certain quota of “pragmatic” stereotyping—whereas it is genuinely easier, in my experience, to act as though one can avoid mentally assigning group characteristics in the USA and Canada. This, I acknowledge, is very dangerous; there are, for example, many Germans who see through what it is their elites have wrought in Greece. Secondly, that I try to write with a layer of sympathy doesn’t mean that I agree with the positions–for some reason, I always have to emphasize this.

EUians and Eurocrats

The first group I’ll discuss isn’t really a “national” grouping at all, but rather a stratum of mostly continental Europeans who view themselves as first and foremost “Europeans” as in citizens of the European Union. I am going to dub them “EUians” from this point on. On the extreme end, I have met EUians who explicitly believe that European countries should abandon their national languages and just adopt a lingua franca (i.e., English). All in all, they believe that Europeans need to “grow up” and accept that the era of the culturally-defined nation state is “over” and that it is a monkey on the back of Europa herself.

Some of you may see this as a pathetic self-abnegation, and maybe it is. But Europe spent the Cold War and maybe before that as a kind of chessboard on which great powers, including powers within Europe, play their games. The only way to evade this fate is to convert Europe into a single, possibly diverse nation on its own — and the only game in town is the EU.

In this worldview, it is only progress that national politics become increasingly devoid of content, and it is only necessary to build European-level democracy when the Europeans have finally, ironically, swallowed the medicine of their own mission civilisatrice. A case in point that is unfolding right now is the drama over refugees, specifically, how to settle them. Brussels had a perfectly reasonable and fair idea that refugees be allocated to countries in proportion to countries’ relative economic weight. This was met with absolute rejection, particularly by newer EU countries in Eastern Europe, who explicitly do not want even a small increase in the proportion of brown people who live there. Behind these countries hid some of the older, larger countries, whose national politics are already burdened by immigration-fatigue.

To EUians, this can only be confirmation that, at the national-political level, Europeans are only a hair’s breadth away from poking each other with sharp sticks in order to maintain ethnoreligious homogeneity. And they may be. But is it a sustainable solution to gradually dilute their democratic rights? To EUians, it is the only answer.

And that bring us to the inner cadre of EUians: the Eurocracy, the elite bureaucrats whose job it is to ^manage^ European economic and political convergence. One of the principal political functions of the Eurocracy is precisely to circumvent national politics. Eurocrats are to act as would-be philosopher-kings, coming up with reasonable solutions based on scientific principles. Oh, they’re human and can be corrupt and venal, but so can elected politicians. Whence the repeated referenda, and then adopting the Lisbon treaty anyway? Well, if the people say “no,” it’s not like the philosopher-kings are going to come up with a better answer–they already emitted the best answer! That’s why they’re Eurocrats.

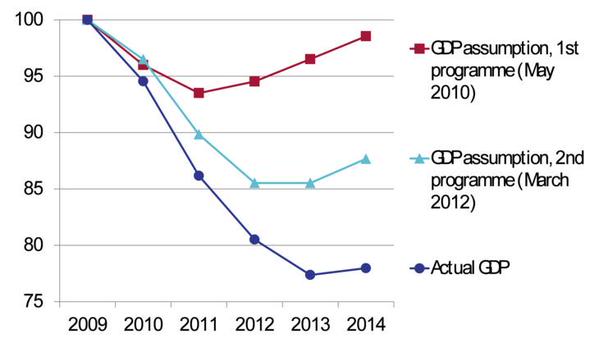

Now consider the position of Greece at Syriza’s election. Yes, some Eurocrats might have been willing to admit that IMF predictions of Greek GDP growth were just the teensiest bit awry. But there is a procedure for these things, and that is definitely not the demand for changes to existing political agreements, which must then go through the process of national democracy. And Greek leftists just aren’t popular enough to withstand that in the rest of Europe, quite the contrary–by making explicitly left-wing demands, they have asked other populations that are not left-wing to support what they believe is a long-discredited experiment.

@WhelanKarl but the opposite view implies that democracies can’t sign binding agreements rich is surely crazier

— Dan Davies (@dsquareddigest) June 23, 2015

No, the from the Eurocracy’s point of view, the correct way to go about solving this problem is by the baking of fudge. If Syriza had agreed in February to support something memorandum shaped — taken the short-term pain of adopting a kolotoumba — the Eurocracy could have given it a little quid pro quo through the back doors of Brussels. But for EUians and Eurocrats, the bad signs started off very early — choosing ANEL over To Potami as a partner. Readers here probably think of To Potami as a Quisling, capitulationist part, but for the Eurocracy, an alliance with To Potami would have signalled that Syriza could be mollified ultimately through fudging an agreement and was not itself a dangerous populist party. But Syriza chose the spear-carrying nationalist Greeks instead.

So from their perspective, Syriza wanted to play populist politics on the open field of democracy and is reaping what it sowed. Europe does not, cannot, should not have room for a populist left, regardless of whether or not the policy proposed makes sense. European politics is about giving cover, and rational, professorial arguments embedded in a dangerous “democratic mandate” framework is just not on. Even this referendum, which the now apparently non-existent proposal might actually win, is a simply unacceptable exercise that, if repeated elsewhere, will destroy the European project, which is an inherent good that cannot survive the popular sovereignty of barbarian peoples.

The poster children

This is sometimes an overlooked aspect of the discussion, but the views of Baltic and East European states do matter. Some of the Baltic states took very painful medicine recently, and not medicine that different in character from what Greece was being asked to take, but has either refused (under Syriza) or only fudged (under ND, etc). And a lot of these countries have populations that are already poorer than Greeks are now.

Now many of you will retort that these countries, instead of joining in solidarity with the creditors, should likewise have the higher ideological standards that Greeks seem to have. But from their perspective, they embraced austerity and social pain as a manner of slicing off their own forearm in order to escape from the bear that has it by the wrist. Yes, I’m talking about Russia. I know that a good number of readers here think of Russia and Vladimir Putin as a kind of last-stand resistor against “AngloZionist” world domination, but for these countries, what they want to know is how soon the West can bring them that sweet, sweet AngloZionism.

So in a sense, Greece’s apparent cozying up to Putin is in some ways a worse affront than its apparent sense of entitlement. Greece is playing with existential fire for these countries, instead of thanking its lucky stars that’s it’s under the AngloZionist umbrella and putting their grandmothers on ice floes of austerity in gratitude.

(As I said above, I am painting with a broad brush. I have an Estonian colleague who is at least neutral on the matter of Greece, but it is clear to me that in terms of European politics, the existential threat of Russia is not far from his mind in any discussion, and Russia for him is his people’s most recent colonial dominator, not the EU.)

Germany (and Northern Europe)

Germany and German politics have been conceived as the other pole in a kind of Athens-Berlin conflict, as Germany is the Eurozone’s largest economy and its most successful. A lot of things have been said about the German role, and some of the criticisms are correct. And it’s true that to some extent, popular tabloid German media is all about the lazy Greeks, lolling about in the sun with one hand in the pocket of the hardworking German. It’s become a cliché.

But one thing to emphasize is that the debate about economic reason itself is quite different in Germany. Outside of Germany, many people can agree that Yanis Varoufakis’ proposals are economically reasonable and possibly even mainstream while criticizing him for his political approach. But within Germany, the proposals themselves—and the logic of anti-austerity thinking—are widely seen as coming from another planet. That’s because popular discussion on economics within present-day Germany does not really emphasize the notion of flows and balances. What does it matter that everyone can’t simultaneously be an export superpower? It’s everyone’s duty to try and find something they can offer to the world, and in terms of nations, that is expressed in terms of their export power. The US import “power” is viewed by many Germans as an unsustainable boondoggle…but the German export power is not. Germany even exports to the exporters.

From this perspective, the proper domain of economic policymaking isn’t to be playing some kind of Rube Goldberg game of who should be paid what when to make the balances work out, but instead it is about removing the obstacles to economic agility and to everyone reaching a Platonic state of optimal social contribution. The German mainstream isn’t like English-language conservatism — you can believe in principle in a generous welfare state along most of the German political spectrum, but it needs to be a welfare state designed around facilitating life transitions. And that sometimes means giving employers a little flexibility.

It’s on this basis that left-wing government in the rest of Europe provokes little sympathy in Germany, particularly in the case of Syriza (but not even French dirigisme gets any quarter). From the German perspective, far from Syriza having been forced to retract its programme, the last proposal of the creditors was actually quite generous and full of compromises on the things that Germans think matters. Syriza’s Red Lines are exactly the things that show that Syriza isn’t seriously different from any other clientelistic party of Greece, and therefore it deserves no sympathy, leftist or otherwise. Germany is willing to open its pocketbook to Greece — through the back door, of course, via Eurofudge — to ensure that Greece looks like a success story. But only if things like pension reform, privatization, labour reform, take place, and not just in a recalcitrant way, but in a way that shows that the Greek government believes in a reasonable “soziale Marktwirtshaft.”

But, from a German perspective, Alexis Tsipras wants to run non-surpluses without figuring out what Greece’s contribution to the world will be as it is, and neither the Eurozone nor the EU itself needs that. In fact, Tsipras wants to propagate this ideology in Europe elsewhere, and to them, that’s neither right nor tolerable.

Finally, Greece

Even with the proposals offically off the table (the fact that a referendum on them is a dealbreaker is in itself very telling!), the referendum is a useful exercise, especially if the “real” question in people’s minds is formulated correctly. It’s important to know “for real” if the kind of thing that the creditors were asking on Thursday would be acceptable to the average Greek, at least in its broad outline — not just some deal, but that deal, even if it is hypothetical.

But a lot of readers here may be disappointed to know that many Greeks would vote for such a deal anyway, even if it meant that Greece became a “debt colony” of the EU. Why would a people voluntarily choose such abjection, even if the Grexit path is hard?

The truth is that Greece sits in a perfect storm of historical factors and cultural memes that primes it specifically to be a chief candidate for a crisis like this. And the form that Greek nationalism has taken up to now doesn’t help at all. At the point at which Greece is “finally” free to take up its place in heart of the Europe whose mother it is, how is it conceivable that it could be facing ejection from what was supposed to be Europe’s cornerstone? How could it be possible that Greece could actually always have been, effectively, an Orthodox Turkey, when it suffered so much under the Ottomans? And how likely is it that, left to their own devices, the Greek elite would actually themselves choose to turn the corner and build a state administration as good as Germany’s? Isn’t it more likely that outside the Euro, Greece will just follow it’s old trajectory, and not become the devalued competitive powerhouse that Grexit-boosters believe it can be?

These are the questions that Greek citizens are going to be asking themselves over the next week, the real issues of the referendum, and it may be that a lot of participants on Ian’s blog won’t like the answers they come up with. Because a “No” most likely means a Grexit forced by the creditors, and while I believe the Greek government is technically correct in not making this explicit, everyone knows what it means. But it is nevertheless important to have had this exercise, because whatever the outcome of the proposed referendum, it will be contingent on and subordinate to the democratic choice of a people, exactly what the Eurocracy has been avoiding, unsustainably in my opinion.

(Brief Ian notes:

1) I asked Mandos to write this because I think it’s important.

2) Greece has now imposed capital controls. Five years later than it should have been done, but a good step.)