The Course of Empire by Thomas Cole

The coronavirus has been striking for the fact that Asian societies have mostly handled the crisis competently (though there’s been variation in how competent), and Western elites, with some exceptions (Germany, for example) have not. At the extreme incompetence level are the US and the UK.

Let’s chalk this up to aristocratic elites. Aristocrats, unlike nobles, are decadent, but don’t stop with that word; understand what it means.

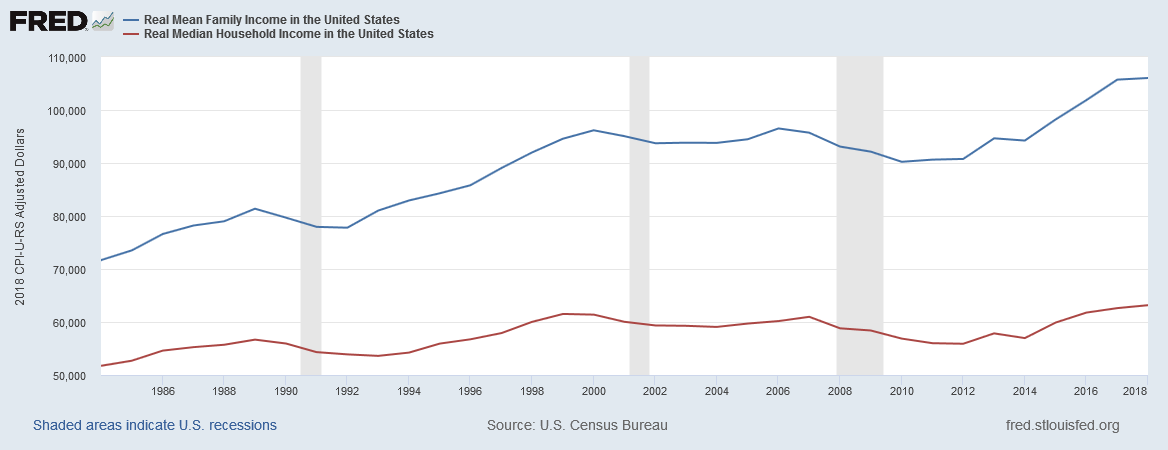

Elites who are not aligned with the actual productive activities of society and are engaged primarily in activities which are contrary to production, are decadent. This was true in Ancien Regime France (and deliberately fostered by Louis XIV as a way of emasculating the nobility). It is true today of most Western elites; they concentrate on financial numbers, and not on actual production. Even those who are somewhat competent tend not to be truly productive: see the Waltons, who made their money as distributers–merchants.

The techies have mostly outsourced production; they don’t make things, they design them. That didn’t work out for England in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and it hasn’t worked well for the US, though thanks to Covid-19 and US fears surrounding China, the US may re-shore their production capacity before it is too late.

We also have a situation where Western elites are far removed from the actual creation of the systems they run. This is most true in in the US, and to a lesser extent in the UK, which did not suffer the massive bombing and destruction of most of the rest of Europe (the Blitz was minor compared to the bombs dropped on Germany, for example). Of course, reconstructing bombed societies is not the same as pulling oneself out of poverty.

The best handling of the coronavirus crisis in the world was possibly Vietnam, who are run by a generation that just pulled themselves out of poverty. Other excellent handling has happened in societies which still remember times of poverty or which were conquered and set free (Japan/Germany). China’s Xi, probably the most incompetent, also managed the crisis badly, but still better than the US/UK: Once he got serious, he got really serious. Xi, while a princeling, had a hard early life and was forced to work on the communes and so on.

This is all standard three-generation stuff: The first generation builds, the second generation manages, and the third generation wastes and takes it for granted because they’ve never known anything else. Sometimes that extends to four generations or more, but that requires a system which properly inculcates its elites, plus something to force the elites into at least some of the same experiences as the peons. We do not have that kind of a system.

Nobles, as Stirling Newberry explained to me years ago, are elites who make a point of being better than the people below them: better fighters, better farmers, and so on. Aristocrats are people who play court games, which is what financialized economies supported by central banks and bought politicians are. These people aren’t even good at finance. They were actually wiped out in 2008, but used politics to restore their losses and they were/are wiped out by this crisis, but are using politics (the Fed/Congress/the presidency) to restore their losses. The Fed is doing one trillion of operations a day.

So our elites are fantastically incompetent even at finance. The vast majority are completely disconnected from actual production, at best they are distributors. All they are good for is playing court games, i.e., politics. They can’t manage the real economy, they don’t run it, they don’t live in it, and they aren’t subject to its rigors. They live in a Versailles, almost completely disconnected from society except in crises, when they print money to save themselves, and download costs onto the peasantry.

So our elites are fantastically incompetent even at finance. The vast majority are completely disconnected from actual production, at best they are distributors. All they are good for is playing court games, i.e., politics. They can’t manage the real economy, they don’t run it, they don’t live in it, and they aren’t subject to its rigors. They live in a Versailles, almost completely disconnected from society except in crises, when they print money to save themselves, and download costs onto the peasantry.

A society such as this cannot survive in this form. Eventually there is an existential crisis which cannot be papered over by the printing of (virtual) money. Perhaps it is a real economic collapse, perhaps it is a natural catastrophe of near-Biblical proportions, or perhaps it is simply the peasants revolting and paying a visit to Versailles.

The vast spread of guillotine memes over the past four years should alarm our elites, but mostly, they seem to feel invulnerable and are still working to preserve their position in the system rather than fix the system and the society. You can see this in how Democrats are standing up a clearly senile Biden and denying the peasantry health care, even in the face of pandemic.

An elite which refuses to manage the economy will either cause its own end, the end of its country’s prosperity and dominance, or both.

Often both.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.