Jane Jacobs came to prominence with the publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which examined what made cities succeed and fail in extremely minute detail–such as how pedestrians walk on sidewalks and what makes parks safe. It’s a brilliant book, and reshaped urban planning, but I’ve always found her economic duology, The Economy of Cities and this book more useful to my interests.

Jane Jacobs came to prominence with the publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which examined what made cities succeed and fail in extremely minute detail–such as how pedestrians walk on sidewalks and what makes parks safe. It’s a brilliant book, and reshaped urban planning, but I’ve always found her economic duology, The Economy of Cities and this book more useful to my interests.

Cities and the Wealth of Nations was published in 1984, and starts with the observation, and case, that the economy of much of the world seemed to have gone off track in a semi-permanent fashion: Something had changed from the post-WWII economy, something which downshifted the economy.

When I first read this book, around 1990, I didn’t think much of that position, but I now know it’s true: Between 1968 and 1980 a vast variety of economic and social metrics all shifted to new tracks; bad tracks. From inequality to wage growth to productivity to growth in the third world, it all went bad.

Jacobs thinks that the way we analyze economies is wrong from the bottom up. Nations, to Jacobs, make no sense as economic units. Canada and Singapore and Britain have almost nothing in common except the fact that they are sovereign units.

To Jacobs, as one would expect, cities are the fundamental economic unit. It is in cities that new work, new industries, are created. It is cities which generate economic forces, forces which affect non-city regions unevenly.

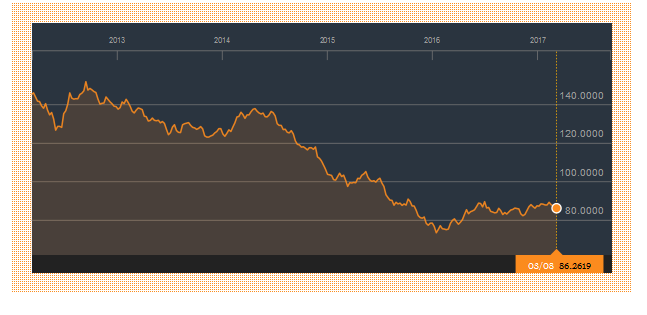

When you lump cities together with non city regions, economics gets ugly. Part of this is feedback: Because cities are the fundamental economic units, when they grow, they should receive the feedback of imported items growing cheaper; and when they are stagnant or shrinking, imported items should become more expensive.

Put simply, cities should have their own currencies, but don’t. They are lumped together with other cities and with non-city regions, and the import/export effects of those regions swamp what each city needs.

In sovereign areas, with multiple economically active cities, this tends to crush all cities but one: You can see this most clearly in England, which used to have many economically active cities and which, as of Jacobs’ writing, was down to two: Birmingham and London.

London, basically, drove the value of the pound. This was inappropriate to the needs of other cities and strangled them, turning them economically inert: They were cities only in the sense of their populations, they were not economically viable cities where large amounts of new work was still generated.

Large hinterland regions do the same thing: If you have a lot of agriculture or a lot of mineral resources or anything else from your hinterlands, the exchange rate will tend to be propped higher than the city(s) need, again strangling growth.

Workarounds for this are always inefficient. You can do what the US did in the 19th century and have tariffs, but that hurts agricultural and resource regions–they simply aren’t receiving what they should from their labour, and is doesn’t eliminate the multiple cities problem.

So, ideally, cities should have their own currencies, and so should non-city regions, so that everyone is getting the feedback they require (steps must also be taken to ensure that currency rates are driven almost entirely by export/import, and not by speculation or by central bank/government manipulation).

This is hard to do in the real world, for obvious reasons, but I agree with Jacobs we should find a way to do it.

Jacobs also spends a lot of time detailing how cities influence non-city regions; almost always in ways that deform the non-city regions and often harmfully.

The first of these influences are supply regions, which produce something cities want. In the modern era, the foremost of these might be Saudi Arabia: It’s rich, because it has oil, but with almost nothing else it is doomed to poverty once oil is no longer important. Economically productive cities want the oil and want nothing else Saudi Arabia produces. When those cities stop wanting that oil (or enough of it), doom will fall. (Jacob uses the example of Uruguay, which was once very prosperous, but never had economically active cities.)

The second influence is regions workers abandon–a place where everyone leaves to go to cities, because there is no work in the region. Examples are distressingly common, and all the screams in the US about immigrants are essentially about such regions in Mexico and further south–places where people can’t make a living, and have to leave.

A variation on this is clearances. New technology displaces workers out of regions. The classic case was peasants forced off their land in Britain, so landowners could enclose the land and grow crops or tend sheep for more money. But this happens all the time in the third world, where subsistence workers are forced off the land for plantations, and is a regular occurance today in China, where people are cleared out of a place so that suburbs or mines or whatnot can be built.

The next type is capital for regions without cities. Jacobs uses the example of the Volta dam in Ghana. It has a huge hydroelectric power supply, but there’s no real value to it, because there is no industry to take advantage of it. All the while, the dam itself destroys local agriculture, hunting, and fishing. Large amounts of money also often go into picturesque regions used for vacations, driving out most of the people who were there before the money arrived, distorting their economy.

Then there are places that were once cities; economically productive, which lose their productivity. Jacobs gives ancient Egypt as an example: the heart of a technologically sophisticated civilization, eventually reduced to mostly subsistence agriculture and no longer one of the beating hearts of the ancient world. A better example, I think, is Europe in the Dark Ages. When the Arabs cut off trade, Europe swiftly became a backwater hole, losing almost all of its advanced cities and spending centuries sinking into poverty before it started growing and advancing again the Middle Ages.

Economically active cities, in short, are powerful, and they often do nasty things to regions that are not cities. Even when what they do seems good, as with demand for oil, or Uruguay’s produce and minerals, it is a boon that can disappear at any time.

Jacobs points out one other thing of note: Backwards cities are best off trading with each other, rather than with the more advanced cities. This was, by the way, a more prevalent pattern in the post-war period before neoliberalism, and in that period growth was faster. The argument is simple enough: Advanced cities often don’t need the goods produced by backwards cities, but other backwards cities do.

Overall, this is an important book. One of the most important I’ve ever read. The point about broken feedback and economic units not making sense is absolutely fundamental and explains a simple fact: City states which can manage to survive the political-military environment, almost always do very well. The ideal economic circumstance is a world of city states, but we don’t have that due to military political reasons (they can’t defend themselves).

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t figure out a way to get the results of city states while allowing for defense.

To me, then, it’s a must-read book, and perhaps Jacobs’ most important.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.