Eras come and go.

Civilizations come and go too.

There have been ecological collapses in the past. For example, one took out the Mayans, and it was self-inflicted. The same is true, on a lesser scale, for Mesopotamia.

Human history is cyclical. It’s only “up trend” in a very long view of things.

In the normal course of events, I would expect that Western civilization would fall. It’s, well, inevitable. I don’t even think it’s that far away in historical time. Might be this cycle, might be a couple hundred years, but we’re clearly coming to the end of our rope.

A civilization ends when it can’t handle problems that are totally obvious, because its ideology won’t allow it to deal with them. In our case, the ideology is economics and capitalism, which insists that decisions must be made based on what maximizes profit. Our ideology doesn’t recognize that profit is a social construction, and doesn’t take into account all the upsides or downsides of doing anything. This, combined with our moral belief that money is “good,” and that the more money you have the better you are, is killing our civilization. (These categories, expanded slightly, cover state capitalist societies like the USSR well enough.)

These problems are acknowledged; just as most of the problems which led to the fall of the Roman Empire were acknowledged, but we refuse to fix them. Every once in a while, an FDR will roll around and patch up one part of the problem, but, eventually, we go back to doing the same thing.

Normally this would amount to reactions like, “Oh well, sucks to live in such times.” Nations, societies, and civilizations come and go and it’s very sad, but it’s just how the world works.

The question is, “Is this time different?’

The argument is scale. We’re a global society, and we’re causing an environmental disaster that is magnitudes larger than any humans have caused before.

One argument is that, “Hey, people predict the end of the world all the time and they’ve always been wrong.”

Which is true, and that argument will be usable until humanity does go extinct (which, inevitably, it will, the question is only when) because it is a one-time event. That it has not happened to humans in the past does not mean it cannot happen. We’re currently driving many species to extinction. Each species goes extinct only once; species extinction due to environmental problems is dead common, and often due to environmental problems the to which the animal in question contributed.

My best guess is that this time is not the human extinction event, but I make that a matter of probability, not probability based on, “It’s never happened before,” (because it has, just not to us), but simply because I expect the climate and ecology will stabilize at a new norm and that the norm will likely be livable for humans.

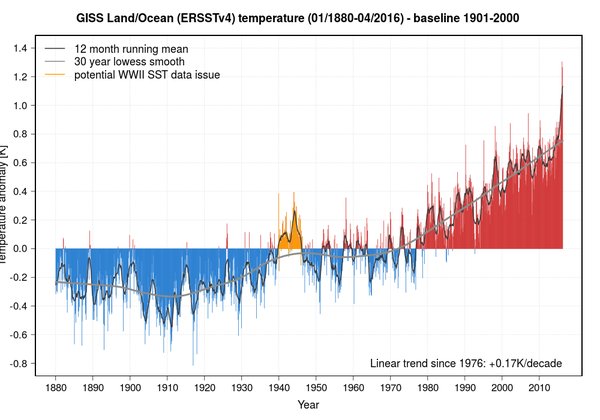

I regard the loss of all coastal cities and lands as inevitable. We are going to lose the Antarctic ice shelf, and it is going to flood coastal lands. Due to the self-reinforcing part of the cycle, especially with relation to methane gas, that’s just going to happen–and probably sooner than we think.

Before then, we’re going to see widespread disruption of weather, which, combined with our overuse and poisoning of aquifers, will mean widespread food shortages, starvation, and mass migration of hundreds of millions of people in one go. There is no question in my mind that we will see wars for water, and they will be major wars.

There are a myriad of knock-on events which will occur, most of them bad. It will be particularly amusing (in, yes, a sick and sad but appropriate way) if Europe is plunged into an Ice Age. This seems quite likely, as the warm water current which keeps Europe much hotter than it should be could be cut off.

But there are reasons to believe that we’ll stabilize, and those humans who remain will go on. This isn’t a 100 percent thing. I believe there is a non-trivial chance we will drive ourselves into extinction, but I judge it as less likely.

On the other hand, I’ve rolled a lot of dice in my life, and I can tell you that the one, ten, or 30 percent probability you discounted can bloody well come up.

More to the point, while catastrophe is now inevitable, the scale of that catastrophe is not fixed and we can still do quite a bit to mitigate and prepare.

Clearly, we aren’t going to be doing any mitigating or preparing for the next four to eight years. The current generation of leadership needs to be replaced, either by youngsters or the last of the post-war liberals with integrity (Sanders and Corbyn are the representatives of that cohort; Sanders lost, Corbyn is polling badly, though I haven’t written him off).

This is where we are. Our civilization is heading into one of the periodic crises that civilizations go through AND, not coincidentally, we have an ecological disaster of unprecedented scale barreling down on us. The first has so far made it impossible to deal with the second, but it is also our best chance, because it promises the possibility of new leadership with new priorities on the other side.

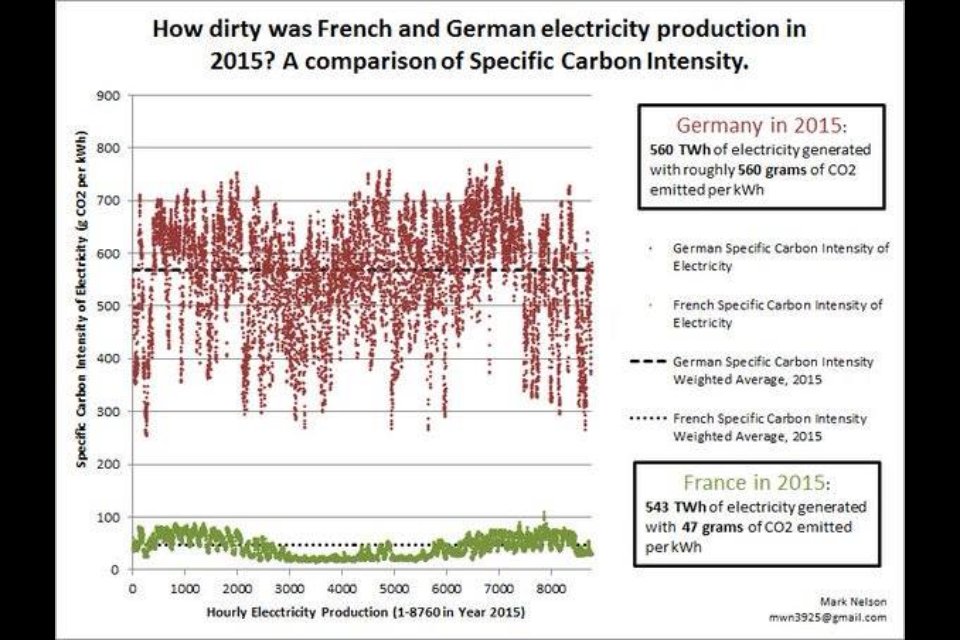

But we must find a replacement for our current economic ideology, as it has served us very badly. We are also going to need to take a hard look at our political ideologies, whether “democratic” or authoritarian, because they have performed no better, being unable to even so much as slow the onrushing night.

Life, in general terms, is going to spend a long time getting worse for a lot of people. There’s a lot of triumphalism about how great our world is, and stats to back it up (stats I don’t trust, but that’s another post), but even if it’s 100 percent true, this “greatness” is time-limited. It has already reversed for many people in the core hegemonic power, where we have had an absolute decline in years lived, as well as huge shocks rolling through the birthplace of our civilization, Europe.

Expect this. Bake this into your plans. Things are going to get worse, and you should be prepared for that, not just physically, if you can, but psychologically. Periods which are shit for decades or even centuries are common in human history, and people keep on keeping on.

Trump isn’t the end of the world, if the end of the world is coming. He isn’t even the start of the end of the world. He and various other events which will occur soon, are at most, the beginning of the end of this period of history.

At the other side of this crisis point, we will either have a society which can deal with these problems well enough to save hundreds of millions to a billion or two lives, or we won’t.

And that’s a set of issues far larger than Trump.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

One of the problems with how we are educated and how we work is that almost all of it is “grading on a curve.” What matters is what our teacher thinks of us; what our boss thinks of us. Except when it comes to sickness, nothing else matters even nearly as much.

One of the problems with how we are educated and how we work is that almost all of it is “grading on a curve.” What matters is what our teacher thinks of us; what our boss thinks of us. Except when it comes to sickness, nothing else matters even nearly as much.