While the EU was considering more sanctions against Iran because it attacked Israel in retaliation for Israel bombing its embassy, Russia is sending Iran:

Meanwhile America is threatening China that if they don’t stop sending Russia “dual use” goods, the US will slap on more sanctions.

Boo hoo.

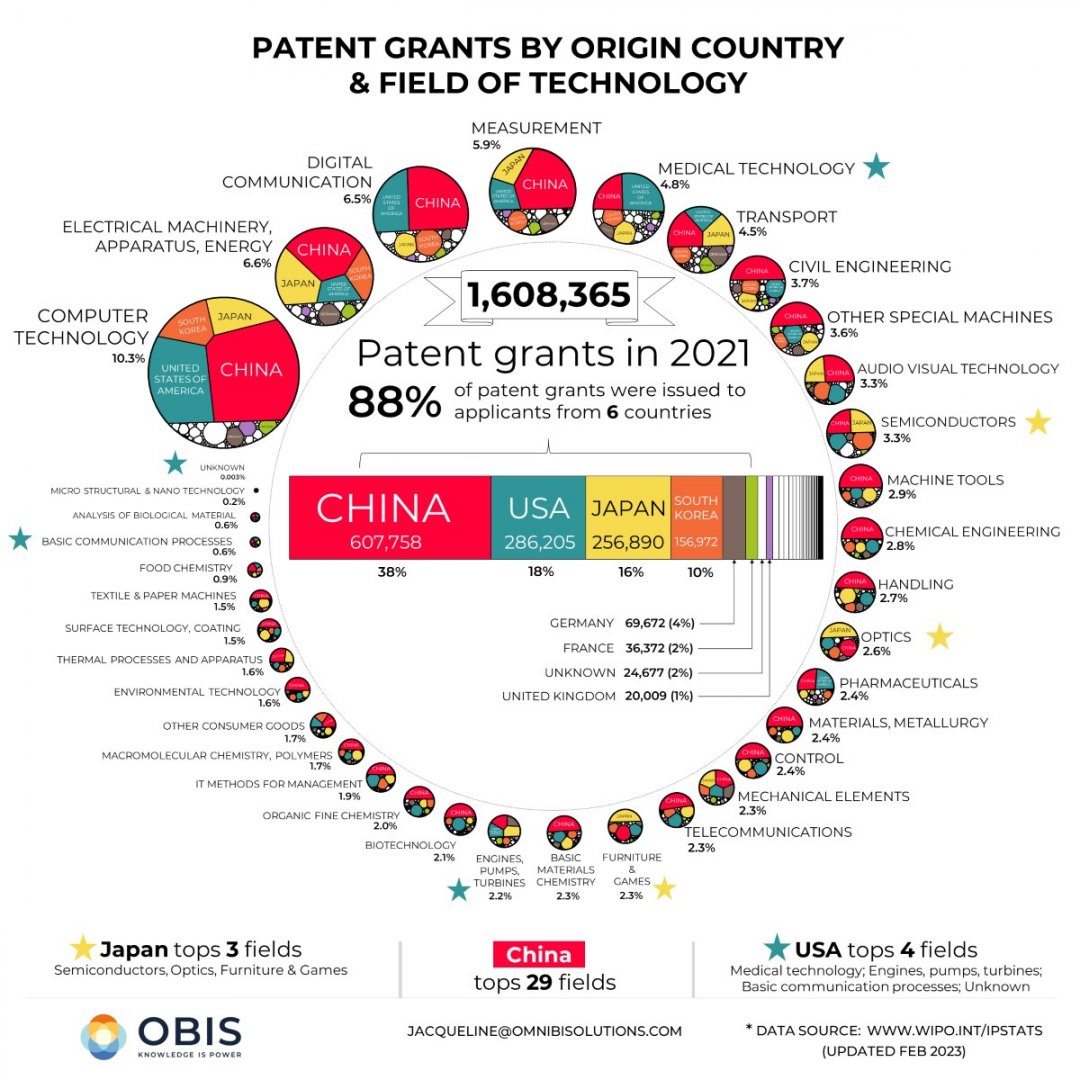

Let us remember the results of chip sanctions. China now owns the legacy part of the industry, and is making progress western “experts” said would take decades in years. Huawei has recovered from the sanctions and created its own OS. It is now a massive electric vehicle manufacturer in addition to everything else. BYD will soon become the largest EV manufacturer in the world, eclipsing Tesla. Something about its cars being cheaper, and Tesla gave up on building a cheap version of their cars. Maybe Tesla will survive because the US keeps all Chinese EVs out, but my guess is that if Musk stays CEO, Tesla’s best possible future is as a luxury EV manufacturer. Their “Cyber Truck” is a disaster.

Iran has built a formidable military with hypersonic missiles while under sanctions, sanctions which started at the same time the Islamic Republic was created. But now, what I’m sure happens, is that China sells Russia goods and Russia trans-ships them to Iran. That hasn’t undone the sanctions completely, but as the world moves away from using the dollar as the medium of trade and routes around US, EU and anglosphere banks, the effects of the sanctions will continue to diminish.

There’s very little that Iran needs (though still some) that China and Russia don’t make. And anything sold to Russia by, say, India, can also make its way to Iran. Cutting Russia off almost entirely gives it no reason to play by Western rules, and it doesn’t.

This is especially true now that America has taken Russian reserves and will be giving them to Ukraine. Anyone who trusts the US with their money who isn’t a complete ally, or satrapy, is a fool. There’s a reason why money used to be frozen before, but not actually taken. There’s a big difference between the two.

That’s after prices dropped massively. The simple fact is that US natural gas costs a lot more. Russia was selling Europe and Germany oil and gas for bargain prices. Russia’s still willing to sell, but Europe has its head up its ass.

The recent history of European industry is simple. When the Euro came into effect, it raised everyone’s prices except Germany’s, pretty much. Industry in all of Europe except Germany was badly damaged (this was especially bad in Italy which was more of an industrial power than most realized.) Germany, in effect, received a subsidy: the Euro was worth less than the German Mark.

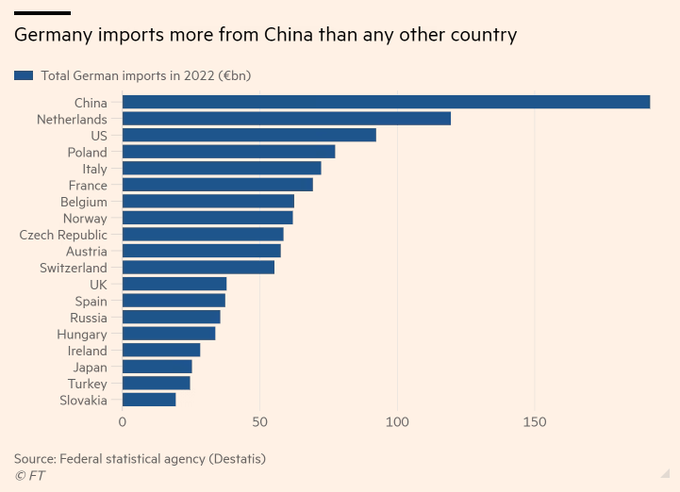

Germany has (had) a lot of heavy industry: a lot of energy intensive industry. To get energy for this, Germany got cheap, below market Russia oil and natural gas. Russia got bulk sales of one of the few things it had to sell and Germany kept its industry competitive.

Those days are over, essentially permanently.

And the problem is that Germany’s dominance was in legacy heavy industry and automobiles. They aren’t creating a lot of new tech and science. They don’t have large new industries developing. They don’t have scale costs like China does. They relied on being very efficient and already dominating industries.

But those industries are leaving. A lot of them are going to America, the actual company facilities, but the production is, effectively, also moving to China and other countries.

I know I’m a bit of a stuck record on this (do youngs understand that simile?) but Europe is walking into its decline with its leaders acting as if it’s no big deal, indeed as if they are, to use my father’s crude insult still “King shit of turd island.” Sanctioning Iran, lecturing Africans and acting as if they are superior in every way: the only truly civilized people in the world.

Even as they do, the foundations of their prosperity, their “garden” are eroding out from under them at the speed of soil blowing away during the Dust Bowl.

They’re insane. Completely detached from reality, and some of the stupidest elites in the world, even exceeding America’s very high bar.

The Sun always sets. European leaders seem determined to make it set as soon as possible.

You get what you support. If you like my writing, please SUBSCRIBE OR DONATE