** MANDOS POST **

In several recent threads on this blog, we discussed (i.e., argued passionately about) the current goings on in Europe (Brexit, Greece, Italy, etc.) as signs of the impending decay and demise of the European project. I used to share this view to some extent, because I too am sometimes in the grip of a moral fallacy that haunts left-wing discourse: that things that are good, work, and things that aren’t good, don’t work. I actually think that in the bigger picture, this is true, but only in the largest temporal and spatial frames. In the medium term, lots of things that are good, are not stable enough in context to work (as in, be sustained for more than a short period of time), and lots of things that are not good, are nevertheless stable enough to last decades and even centuries.

Predicting whether, when, and how some particular set of events will cause large institutions to rise or fall cannot be done lightly or easily, and such predictions, when done in the moment, are more likely wrong than right. You should expect unexpected things to occur; there are too many variables. Some people are better at it than others, but you should take even the best track records with a grain of salt. Even two to three years ago, I would have predicted that the build-up of “bad karma” in the European system would have caused the EU to break apart by now. Even a few months ago, the rise of Euroskeptic populists in some countries suggested to me that the situation is increasingly desperate for European unity. However, over that time, and somewhat unexpectedly to me I must admit, it appears that some sort of inflection point has been reached.

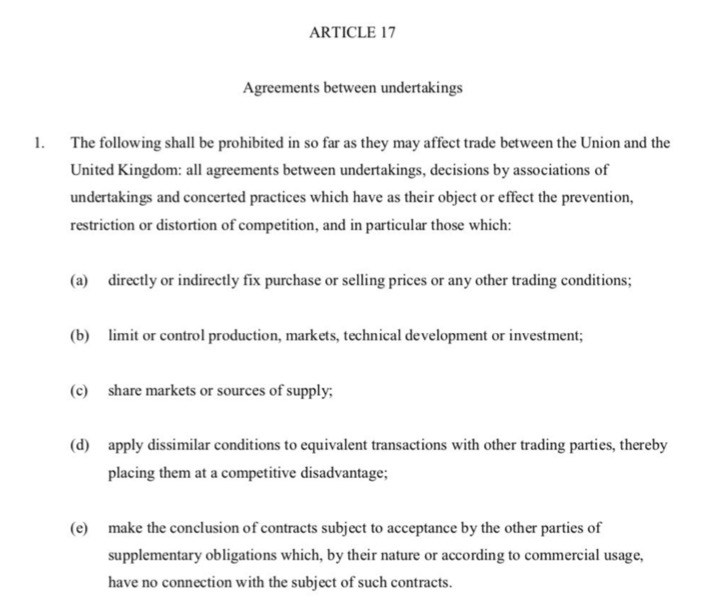

The EU, as it stands now, was designed by a set of people that had different attitudes and goals over time. Therefore, it is a mixed bag, when it comes to good, not good, works, doesn’t work. A good chunk of its institutions were designed at around the peak of the neoliberal revolt against state management of the economy. In the EU, this took its expression in an approach to the economy that militated against state attempts to protect or bolster industrial employment in both public and private sectors. Because Europe does not suffer so much from the “moralized” version of libertarianism from which the US suffers (essentially, that your bank account is a virtual extension of your physical body), there is a stronger commercial regulatory apparatus developed even in the neoliberal era than what other developed “capitalist” countries tend to have. The neoliberal bits, especially the most recent ones like the Eurozone, have increasingly showed themselves to be not good and not working.

But this cannot be taken out of the context of the whole. It’s increasingly clear to me that Europe is still not that far off from the overall intended trajectory of the two generations of designers of European convergence. It is absolutely true that those who built the system had, for a number of different reasons, a deep suspicion of the public and popular sovereignty, even while they were also against outright dictatorship. I generally consider this to be overall not good and probably won’t work in the long run. (But I must note that the designers of the EU also recognized that they might need to legitimize popular sovereignty at a European level and built in provisions for systems to implement it.) However, they believed both in the necessity of European unity (in the modern world, a disunited Europe is structurally, deeply vulnerable), and the difficulty in getting a multilingual, multicultural subcontinent of fallen empires to accept the necessity of unification, so they constructed a system of what are effectively one-way traps to ensure that the cost of departure is always greater than the cost of endurance, even when the system in some matters doesn’t work. The goal is therefore for this endurance to eventually result in a crisis whose only positive-sum resolution is the Europeanization of authority.

With Italy’s effective capitulation to the Commission, and yes, with Greece’s previous compliance, and yes again, with a Brexit that is already providing the necessary object lessons, it appears that the crisis-and-trap strategy is still operating, or rather, it cannot be said to have failed at this point in time. That is, it remains that case that the strategy of making a series of systems that don’t work is working.

Considering that this game of deliberate historical manipulation has real human costs and indeed a known death toll in itself, one may well choose to designate it as not good. But, the evidence is that it still works.

So what would the decline of the European project actually look like? Well, there are, of course, phenomena that are hard to predict directly, like, sudden environmental cataclysms. If I were forced to make a prediction, however, the political coming-apart would probably have to look like one of the following options:

- A situation comes to pass where it is immediately more materially beneficial to leave than to stay (this has not yet happened).

- One or more countries decide to leave a major institution/treaty despite the costs, and they do economically better in the relatively short run after departure. (Brexit under the Tories is not likely to be an example of this.)

- A consensus develops in several countries that long-term economic suffering is more desirable than staying in the EU, even if that suffering is greater than what they might have experienced inside the EU, and they sustain this consensus even after feeling that suffering.

All of this may lead you to consider projects like the European unification, designed explicitly around creating consequences that override popular will, to be not good. I have given you at least three possibilities for it to not work. So I would say, as before, that it is a mixed bag.

Political theodicy is dead. Long live political theodicy.