Plato and Aristotle

Will the next generation of leaders be any better than the ones we have today?

Well, we can guarantee that they won’t be better if we don’t make sure the ideas for better solutions are around.

Milton Friedman and the neo-liberal operatives were very much correct: When a crisis hits, you can only prevail if you already have in place your ideas for the solution. Much to our horror, we have seen that this neo-liberal “shock doctrine” does, in fact, work.

Which is why Ian’s attempts to reformulate a moral, humanistic philosophy for political economy is so important.

(This piece is not by Ian, it is by Tony Wikrent. I (Ian) don’t agree with everything here, but it’s an important post, and thus has been elevated from the comments.)

My approach has been different: Point to the founders of the American republic and emphasize those aspects of their philosophy for political economy we no longer follow, and, indeed, barely even tolerate today. For example, it was generally accepted through most of the first century of USA’s national existence that gross inequality of wealth and income was a danger to the experiment in self-government.

One reason I favor my approach is that, in the end, who you have to convince, above all, are the military and the police; a revolution only succeeds when the people in charge of suppressing dissent begin to refuse to do so. And I simply do not believe that you are going to convince American police and military that Marx or Mao or whoever is the answer. On the other hand, they just might be convinced that the original ideas of the American experiment in self-government have been trampled on and subverted by TPTB – including (most especially) the “vast right wing conspiracy” which has been funded and built up by the wealthy since their opposition to FDR and the New Deal.

A second reason I favor my approach is that the historical record is very clear that socialism, Marxism, communism, and so on DO NOT WORK. It pains and troubles me greatly to see, in reaction to Obama’s failure to deal with Wall Street since the crash of 2007-2008, a resurgence on the left of these failed ideologies. My guru here is Lawrence Goodwyn, the author of what is far and away the best history of the populist movement. What makes it the best? Goodwyn fully understood the Greenbacker critique of the U.S. financial and monetary systems that powered the extraordinary political success of the populists in the 1880s through 1910s. In December 1989, Goodwyn gave a speech at a special event in St. Louis on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the populist People’s Party “Sub-Treasury Plan” for financial reform, Democratic Money: A Populist Perspective. After dissecting how TPTB have left no room for serious discussion of a truly democratic system of money, credit and exchange, Goodwyn observed:

There is another society in our time — what we call “the East,” what we sometimes call “actually existing socialism.” For about 40 years, since Stalin imposed this system on whole populations, an idea floated around in people’s heads over there, in “the East.” The idea was, “We will try to create some space where we can talk to each other and affect the world we live in. To do that, we’re going to have to combat the leading role of the Party. We’re going to have to find some way to get around the fact that all the social space in society is occupied by the Party.”

This idea would float around kitchen tables on the Baltic coast in the 1950s and 1960s. And workers in shipyards would say to each other, “We have got to create a trade union independent of the Party.” Now that is an unsanctioned idea. And they knew it was frightening even to say it out loud; you’d only say it around the kitchen table, around carefully selected brethren and sistren. And the idea would go away, because it was unsanctioned. But then there would be another horrible accident in the shipyard, another insane adjustment of work routines, and the idea would come back, simply because it was the only idea that made any sense. “Work organized by the Party is insane, Poland is insane, our social life is insane. We’ve got to have a union free of the Party.”

Over 35 years of self-activity the world has not known about — any more than the world knew very much about how the Farmers’ Alliance organized Populism — they found out how to do it. And in 1980 they did it. There’s a certain logic in history every now and then. The single most experienced organizer in the shipyard in Gdansk, Poland, who spent 12 years organizing and brooding about a union free of the Party, who had gone to jail scores of times in the decade — learning each time a little bit more about how power worked in his society — the one single most credentialed worker with other workers based on his own activity, is Lech Walesa. There is every now and then a certain justification in history.

Because that movement existed, even though it was repressed by the government after 15 months, it sent a wave of hope across Eastern Europe. What Solidarnosc combatted, by its simple existence, was mass resignation. This resignation was the dominant political reality in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Poland until the shipyard workers of Gdansk became the nucleus of a mass movement, one of those rare moments in human history when people get back in touch with their own subjectivity. That is to say, they don’t lie in public. They say what they mean. And they try hard to say it clearly. They’re not trying to make a speech, they’re not trying to be an orator. They’re trying to be clear, like two people in a marriage struggling not to be political with each other but to be honest. One of those rare democratic moments when reality is projected.

Because Solidarity stayed alive during the years of martial law, and because a man named Brezhnev who put down Solidarity passed off the stage of history and another man named Gorbachev who would not put down Solidarity came on the stage of history, the leading role of the Party this very week is going into the dustbin of history all over Eastern Europe.

You especially need to read the speech if you are wondering what the Greenbacker critique is, the truly “American” response to concentrated economic and financial power. But the important thing for me is that after Goodwyn gave us an incredible educational tool in his history of USA populism, he then turned his attention to the Communist bloc of Central and Eastern Europe and, in Breaking the Barrier: The Rise of Solidarity in Poland, showed us that the same problems arose in both settings, and the same populist solutions prevailed.

Well, to be accurate, let’s modify that to “almost prevailed.” In the USA, the populist insurgency actually elected dozens of populists to Congress, including a handful of Senators, hundreds of state legislatures, and a few governors as well. Out of that, we got the first regulations on railroads, on food production, on pharmaceuticals, the only state bank in USA (North Dakota), state and federal crop insurance, among other things. Even the Federal Reserve system was made possible by the populist insurgency, though it was not really their design. They wanted something very different, but it was the populist insurgency which generated the general clamor for reform of the financial and monetary systems after the panics of 1901 and 1907.

Instead of what they wanted, the populists got the monstrous Federal Reserve – even further removed from democratic control under the rubric of preserving the independence of the central bankers – because the populists’ core Greenbacker critique had been fatally devastated by their 1896 compromise with William Jennings Bryan over his position on silver coinage. This destroyed the populist movement during the 1896 campaign. The story of that destruction, by the way, is one of the most important case studies for those interested in the subject and Goodwyn’s is really the only solid history of which I know.

The last great surge of populist success involved the Non-Partisan League in North Dakota in the years just before World War I. At that time, the ideologically weakened populist movement was pretty much eradicated by the anti-German hysteria deliberately whipped up during the war. Chris Hedges provides the history in the opening chapters of his book, Death of the Liberal Class.

It is highly pertinent to ask here: Why weren’t the socialists and communists wiped out along with the populists during the war? There are, I believe, three reasons. First is not really a reason; the fact is, the socialists and the communists were also attacked. Especially targeted, I believe, were the networks that had been established by the European revolutionaries who had fled to America after the failed revolutions of 1848.

A digression here. These networks of 48ers were integral to the electoral successes of Lincoln and the Republican Party. They also were integral to the success of the Union on the fields of battle. There is a new book out, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the Civil War, by Don H. Doyle, which details how crucial was the role of the European revolutionaries who remained in Europe, in saving the Union during the Civil War. The story starts with Queen Victoria, who detested the American experiment in self-government and, after some hesitation and misgivings, then British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston finally decided, in September 1862, to dispatch a British army and fleet to Canada. This would create the northern half of a pincers to choke the American republic; the southern half of the pincers were the French and Spanish forces which had already landed in Mexico and the Caribbean, with British assistance, in December 1861 through January 1862.

At this crucial point–just when the British oligarchs thought they could finally get away with crushing the obnoxious experiment in self-government–the Union Army won at Antietam. When news of the victory arrived in Europe, massive pro-Union demonstrations erupted. These demonstrations were led by supporters of Giuseppe Garibaldi’s fight for Italian unification and independence, the most militant manifestation of the general, European progressive, anti-monarchical sentiment at the time. On October 5, 1862, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, many garbed like Garibaldi’s red shirts, filled Hyde Park, London, and elsewhere in England. Palmerston quietly abandoned his preparations to militarily assist the Confederacy.

But let’s return to the crushing of American socialism and communism, and what I believe was the second reason it was not as thorough as the annihilation of the populists. It was not until after the Bolsheviks seized Russia that socialists and communists in America could be painted by opponents as “the Bolshevist menace.” The crackdown of socialists and communists thus became particularly severe near the end of World War One and after. Lasting, of course, through the 1920s and 1930s, right up to today.

But for me, the most important is the third reason. The socialists and communists who survived in the USA, I believe, were allowed to survive, because they were funded and controlled by what used to be called The Eastern Liberal Establishment. This is a point about which many on the left get hysterical. But the facts are detailed in Caroll Quigley’s Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time. And if you don’t want to take the time to wade through that massive tome, just look into Corliss Lamont, the major funder of American socialism in the 1960s, note who his father was, and don’t shy from doing the math of putting two and two together.

What about the European revolutions which overthrew the socialist states in the 1980s? The great promise and hope there was crushed by the adoption of Western neo-liberal capitalism. Which, not surprisingly, since it is funded and promoted by a bunch of rich pricks, ended up, when applied to Russia, Hungary, Romania, etc., creating a new oligarchy of rich pricks. And this should be an abject lesson for the left of the point I am making: When a crisis hits, you can only prevail if you already have your ideas for the solution in place. The crisis in the 1980s hit in Central and Eastern Europe and the only ideas ready for use were those of Milton Friedman and the other amoral pigs of the Chicago School. There should be no wonder or shock at the results.

OK, so socialism and communism may not be any better than capitalism in preventing the rise of a repressive, authoritarian political regime. But what about the “tool kit” of Marxist class analysis? Isn’t that valid, even useful? Well, since you ask, I’ll answer: No. I’ll even explain why.

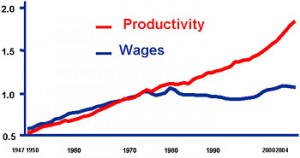

Marx believed that classes were defined by income and ownership. While he engaged in some sociological speculation about how people change as incomes rise, he was mainly concerned with how the rich exploit the poor. The problem is, the really important class division in society is between producers and predators – the Leisure Class, as Thorstein Veblen termed it – and there are a lot of producers that end up being included and condemned in Marx’s capitalist or owner class.

The implications are pretty damn important. Lenin’s and Stalin’s determination to annihilate the krulaks in Russia was one result. But the krulaks were the backbone of agricultural production, they were the producers. Oppressing and dispossessing the agricultural producers resulted inevitably in a catastrophic collapse of agricultural production. So you get the famines of the 1920s and 1930s, which, it should be noted, only made it easier for Western elites to portray the Bolsheviks in the worst possible ways.

Marxist class analysis also is not much help when it comes to climate change, because all of Marx’s classes use energy. Just look at the sources of carbon in rich versus poor countries. What spews more carbon per economic activity: heating a home and cooking meals in a rich, Western country using electricity or even natural gas from the grid? What about cutting down trees and burning them in a poor country?

We need $100 trillion in investments over the next two decades to entirely replace fossil fuels. Of what use is Marxist analysis in getting that done? But Veblen’s producer / predator analysis – that the major struggle in modern economies is the one between industry and business – is immensely valuable. Consider the capitalists who want to build the 1.7 billion home solar power systems we need; Good – even if they are still capitalists. What about capitalists who want to stymie the move to renewables, like the Koch brothers, in order to continue profiting from fossil fuels? Or capitalists who want to identify and buy up emerging companies in renewables and add them to their already immense corporate empires, such as General Electric, and cartelize the industry? Bad.

Now, there are a lot of people on the left who try to avoid the opprobrium of an open embrace of socialism or communism, most often by arguing that the American republic was intended, from its very beginning, to be anti-democratic and tilted in favor of the owners of property. This, of course, is the analysis of Charles Beard in his Economic Interpretation of the Constitution. Since I’m already jabbing at many leftist sacred cows, I might as well jab at this one.

I wonder if these people have actually read Beard. According to Beard’s Interpretation, there were two basic interest groups: “…the merchants, money lenders, security holders, manufacturers, shippers, capitalists, and financiers and their professional associates” comprised one group. The other was “… the non-slave-holding farmers and the debtors.” This grouping commits the very same error Marx does: It does not distinguish adequately, as Veblen does, between producers and predators. It is simply too crippling a mistake to lump money lenders, security holders, and financiers in with manufacturers. I will also note here that Beard’s analysis of Alexander Hamilton is completely at odds with the negative way these people portray Hamilton.

And I’m absolutely certain those people who champion Beard’s analysis have never read Beard’s later work, The Economic Basis of Politics, which Beard himself considered more important because it addressed the great misconceptions that had arisen concerning his Economic Interpretation of the Constitution. To quote from the introduction to a 2002 republication of The Economic Basis of Politics, by Clyde Barrow:

…Beard (1945, 62) concludes that “modern equalitarian democracy, which reckons all heads as equal and alike, cuts sharply athwart the philosophy and practice of the past centuries.” These themes are woven together in Beard’s claim that the central problem of contemporary political theory, as well as the motor of contemporary political development, is the contradiction between the ideals and institutions of political democracy and the reality of economic inequality (i.e., classes)…. The fact that neither capitalism nor communism had solved the problem of class conflict led Beard to the “grand conclusion” that it was Madison’s economic interpretation of history rather than Marx’s, that had withstood the greatest test of modern political history. Madison was correct to the extent that he identifies the problem of regulating class struggle, rather than eliminating it, as the central problem of political statesmanship and constitutional development, regardless of the mode of production or any particular distribution of wealth. There is no end to class struggle and, therefore, no end of history (or politics)….

Screw you, Francis Fukuyama, and your neo-liberal sugar-daddies.

As I argued a few days ago, the only power we have is the power of ideas. If you want the next generation to be better, give them better ideas.