Alright, let’s talk about the elephant in the room. The simple fact is that, compared to other developed countries, the US has a lot of gun violence.

One can wave ones hands and say “well, cars kill more people”, or point out that statistically you’re damn unlikely to die in a mass shooting (just like you aren’t going to die from terrorism), yet, relatively speaking, the US has more mass shootings and school shootings than any other developed nation.

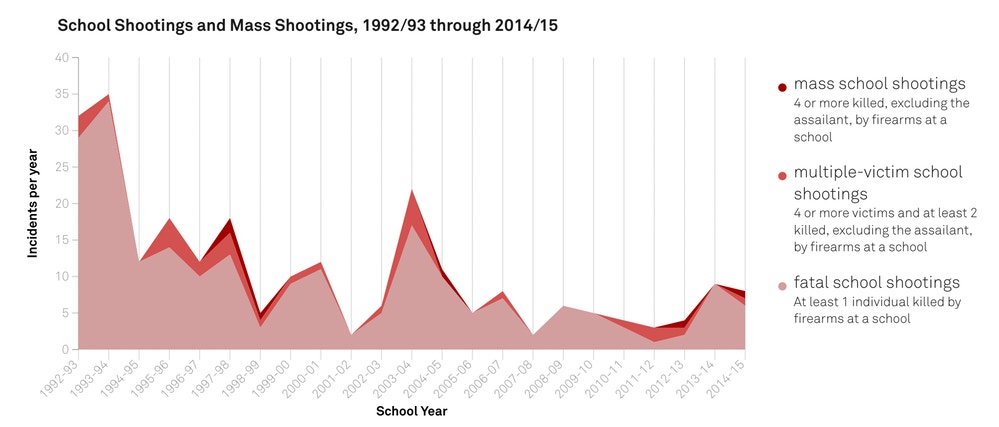

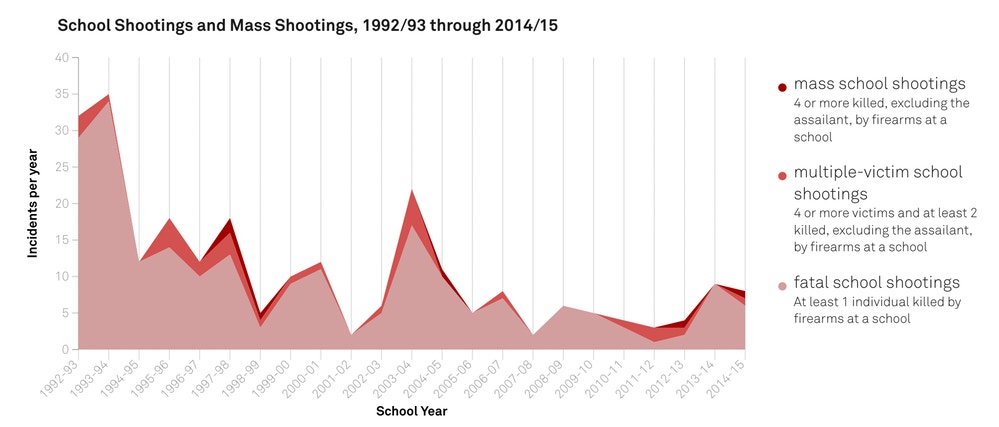

It is important to understand the scale, however. This chart from the Intercept is useful:

Screen-Shot-2018-02-27-at-1.30.01-PM-1519756226 James Alan Fox and Emma E. Fridel, “The Three R’s of School Shootings: Risk, Readiness, and Response,” in H. Shapiro, ed., “The Wiley Handbook on Violence in Education: Forms, Factors, and Preventions,” New York: Wiley/Blackwell Publishers, June 2018.

Alright, so first off, it is INSANE to arm teachers. School shootings, while a problem, are relatively rare, but what we do know is that when people have guns they are more likely to use them. If we were to, say arm five teachers per school, at approximately 128,000 schools in America, we’d have 640,000 teachers with guns. This to stop an average of ten deaths a year from school shootings.

How many of those five teachers with guns would use them? Use them on themselves, their students, their families or other people? I guarantee, absolutely, that it will be more than ten people a year. Far, far more.

“Hardening” schools is deranged. Having cops and guns and so on in schools is a pathetic admission of social pathology that is off the scale and it’s bad for students. Schools should not be prisons: well, not any more than they already are by design, keeping young kids cooped up and sitting down when they’d rather be doing something else (and probably should be, but that’s another article).

All right, so much for that argument. let’s move back to our original question. Why is the US a pathologically fucked up mess? Most adult Swiss males have assault rifles, they do not go on killing sprees like Americans do (they do kill themselves a lot, though). Nor do the Swiss have nearly as high gun homicide rates.

Of course, those Swiss have those guns locked up and understand they are to be used for their military duties only.

A comparison of international rates finds that the US has about three times more gun deaths per capita than the next highest nation—Finland, with Austria close behind. But the Fins and Austrians are three times more likely to blow their own brains out, rather than someone else’s, while Americans kill with guns almost as much as they commit suicide with guns.

The summary of a WHO study is worth reading.

Even though it has half the population of the other 22 nations combined, the United States accounted for 82 percent of all gun deaths. The United States also accounted for 90 percent of all women killed by guns, the study found. Ninety-one percent of children under 14 who died by gun violence were in the United States. And 92 percent of young people between ages 15 and 24 killed by guns were in the United States, the study found.

Right…

So, there are two factors here. Social pathology and deadliness. China (not on the above list) has strict gun controls and a lot of violent people. It doesn’t have a lot of gun deaths, instead it has mass killing sprees with knives.

But when you look at those sprees what you find is that they’re less deadly, because while knives are dangerous (very hard to defend against), it’s also hard to kill a lot of people with them.

So the idea that having less guns available would make attacks less deadly passes the sniff test. Of course it would. Remember the Las Vegas shooting? One asshole in a hotel room shooting into a concert crowd?

I have little time for those who say that if deadly automatic weapons with large clips were hard to get there would be less gun deaths from shootings. It is also true that wounds from assault rifles are far worse than wounds from handguns, by the way.

One may wish to argue that there is social utility to people having guns that is worth the deaths. We think the convenience of getting around in cars is worth car deaths. But one has to make that argument. If the social utility is “can fight the government”, well, that’s an argument that isn’t clearly the case. (See this long article for the full “will guns let Americans defeat their government?” argument. ) But, perhaps most tellingly, Americans have been in a long slide to loss of their rights and having guns hasn’t stopped that slide.

One might also argue that owning military guns is an intrinsic good. Owning them and knowing how to use them has social utility in some fashion.

But, again, the more guns, and the more guns whose purpose is to kill large numbers of people quickly, the more gun deaths are possible. And whatever level of social pathology you have in a society which makes people want to be violent, guns will make that violence more deadly.

So let’s talk social pathology. First off, it isn’t intrinsically “multicultural society” because Canada is multicultural and has a lot less gun deaths and murders than the US. I live in Toronto, which is more multicultural than any major American city, and has a lot less gun deaths than many US cities.

It may be that Americans are just a bunch of violent assholes and always have been. The country was won with genocide, and founded in slavery (no, don’t even) and that’s just who Americans are, and they’ve never gotten over it.

I… suppose? Culture is a thing, violence does get handed down from father to son, and from perpetrator to victim, who then goes on to victimize. Beat your kid, and your kid is quite likely to be violent to other people. This is robust in the scientific literature.

But parenting has changed, and parents are less violent to their children than in the past. They’re controlling assholes who give their children no freedom these days, of course, but they generally don’t hit them.

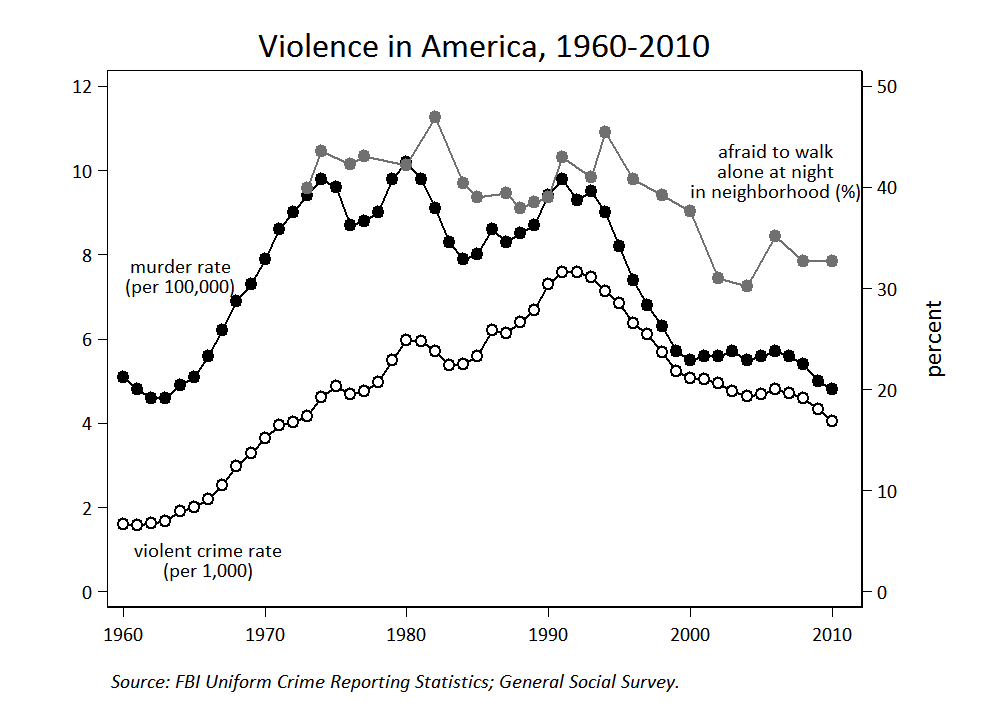

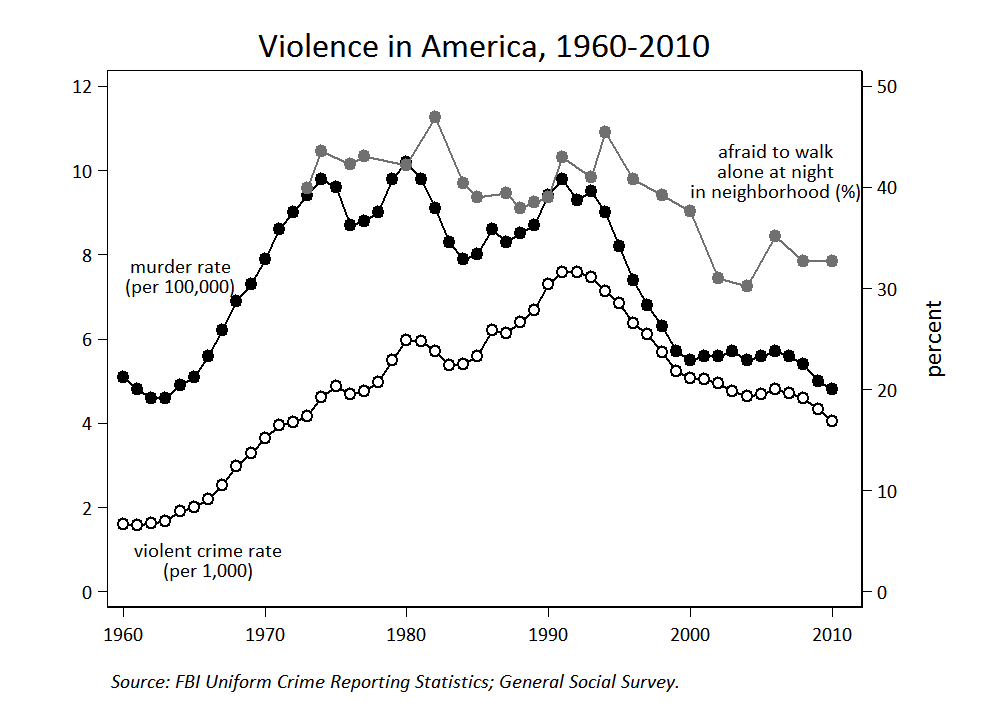

The thing is, the evidence supports this:

Gun violence, in fact, is declining. It rose with the boomer cohort, both because young people commit more crime, and because American society went off the rails starting in the late 60s, but it’s declined since a peak in the early 90s, despite Millenials, a large generation, coming on line.

America is less violent. The 90s was, in fact, the peak, and this is true of school shootings as well.

So, no problem, right?

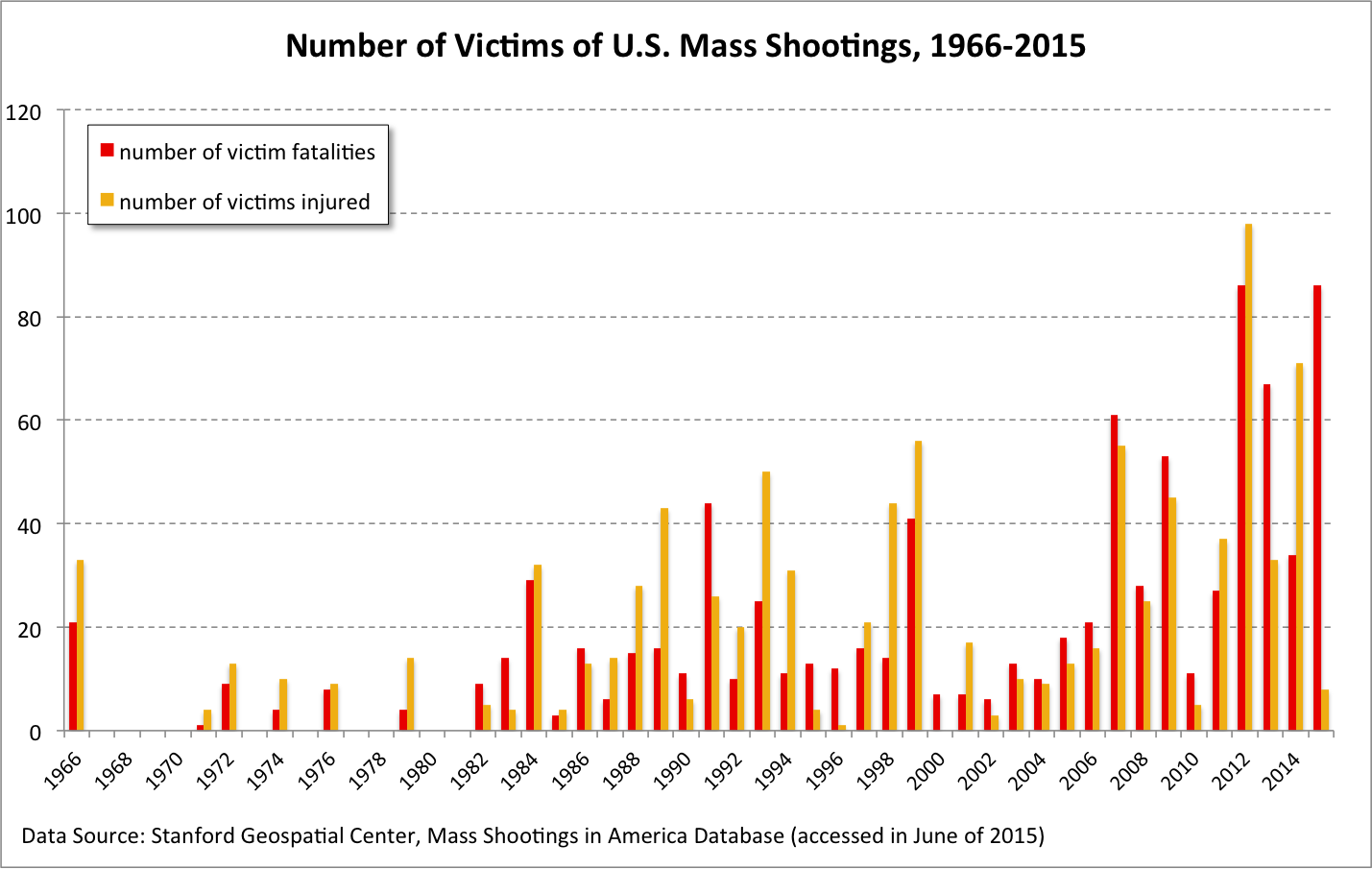

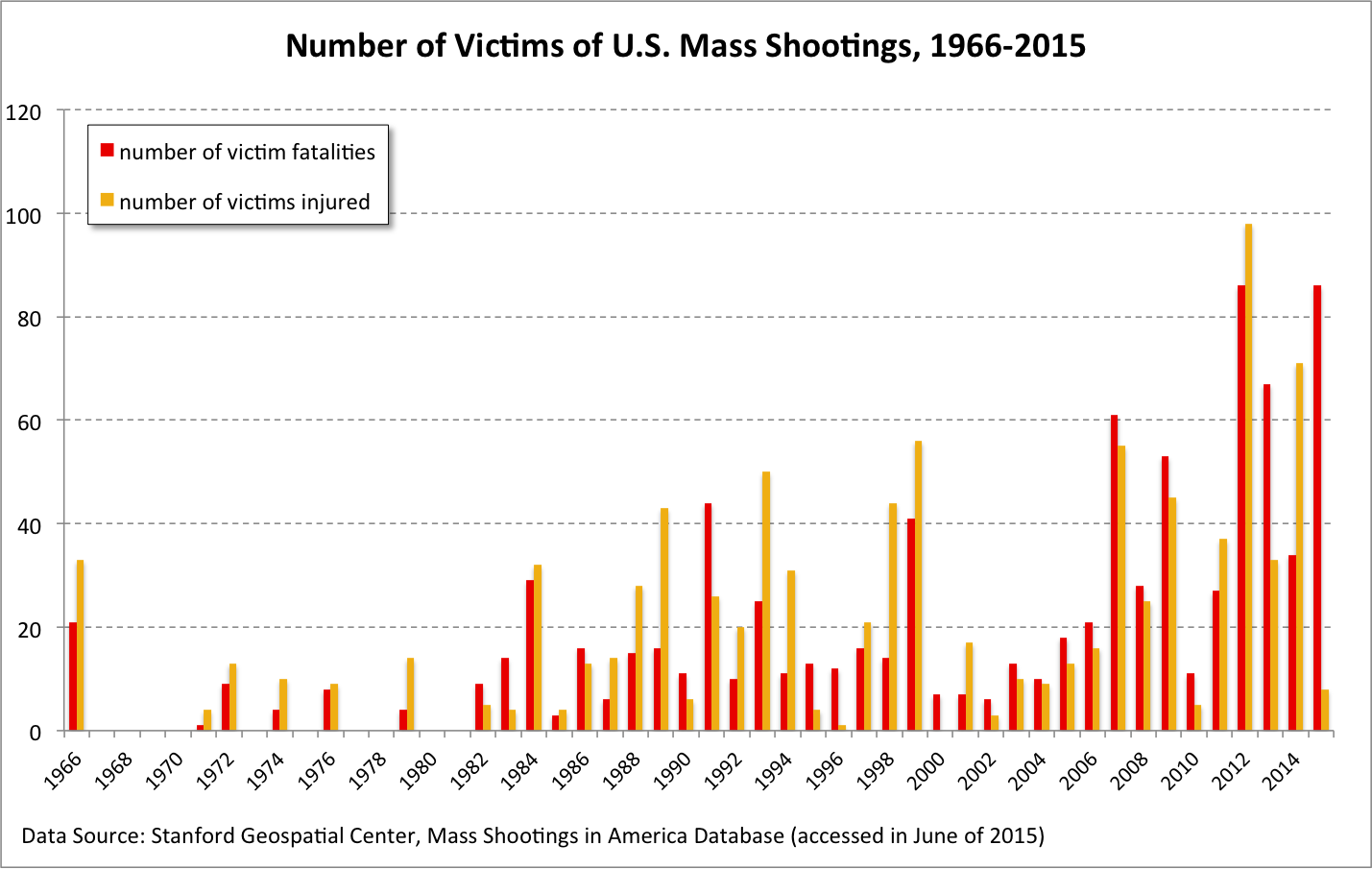

Wrong. Here’s the mass shooting data.

Well—that doesn’t look so good. Americans are killing less retail, and killing more wholesale. Of course, we’re talking a few people, very few, but the far end of the curve has been pushed into mass homicide territory, and it looks bad.

So, how about something simple.

Around the late 60s America’s economy starts to go to shit. Yes, I know this is my go-to argument for a lot of America’s problems, but that’s because, well, it’s true. ’68 is where working white class wages peak. The 70s see social struggle, especially around African American liberation, and a lot of violence (including bombings).

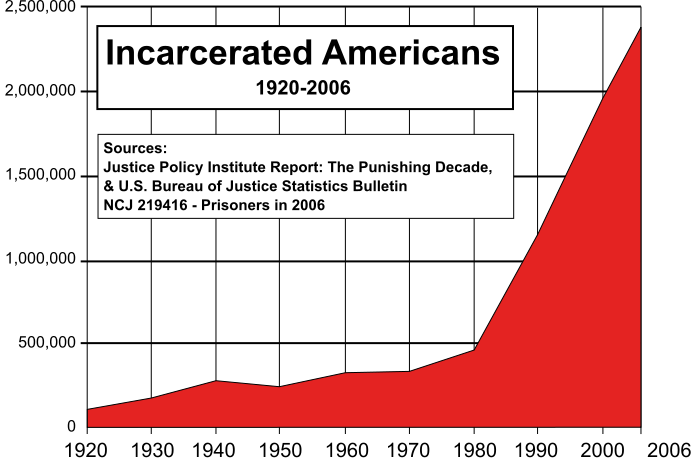

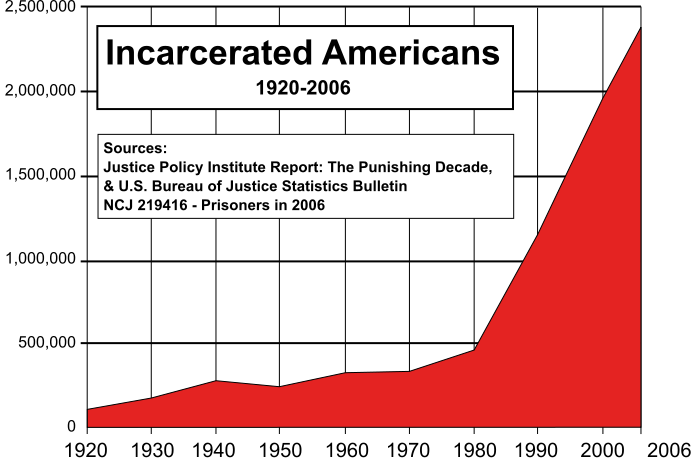

And in 1980, Reagan is elected and he and his movement does this—

BOOM!

Here’s a simple thing well known to criminologists. You put people in prison, they tend to come out nastier than they went in. You criminalize victimless crimes (like drugs) and a lot of people who would never be violent, become violent because they are forced to become criminals to engage in behaviour the state doesn’t want, but which isn’t innately harmful to anyone but themselves.

So, we have a criminalizing trend, an economy which is getting shittier, and a change in parenting from violent to non-violent.

And the kids raised by violent parents (yes, that is the GI generation, don’t say otherwise) are violent when under economic pressure or when stuff they think is their right, and which was legal when they were young, is made illegal.

But as the children become adults who were not raised violently, retail violence decreases despite social pathology.

This is probably aided by the widespread use of legal mood altering drugs, often from childhood, of anyone who shows any spirit or unwillingness to sit like a tranquilized animal in a classroom while a teacher drones on, or in an office, doing meaningless work for an asshole boss for a shitty wage.

Unhappy with your life because your life is, actually, shit? No, no, no. The best way to solve that isn’t to change your life, or society, it is to drug you.

So, kids who weren’t treated violently become adults, and they are, in large numbers, drugged to the gills.

Is this “the cause?” Who knows. But it’s a narrative that fits a lot of the facts and a narrative that doesn’t explain the mass shootings…

Homicide rate drops, mass shootings increase. And very much an American thing, though other nations dip their toe into the pool on occasion.

Why?

Well, perhaps part of it is that the US continues to get worse and worse off. You see this in the opiate epidemic, which I consider to be clearly caused by economic despair moving from blacks to working, lower and lower middle class whites. (The economy dropped off a cliff for blacks in the 80s.)

It isn’t, of course, that the poors always do the deed, it is that everyone is aware that their economic situation is precarious. Lose their job and get blackballed or wind up sick with more than their insurance will cover (easy even with good insurance) and that middle-class American lifestyle is gone. And for more and more people it has just slid away. A hundred thousand here, a million there, a financial crisis over there, and hey, you’re on the street.

Even if it hasn’t happened to you, the knowledge that it can is always there. Economic life in America is a game of musical chairs, with some chairs having spikes on them, and there are not enough chairs period. And if you don’t have a chair to sit in when the music stops, well, your life is endless misery—well, until your life ends.

And the guns are there. And people are angry. And the far-end of the bell curve moves over and over and over and it lands on just a few people. But they have access to military weapons and the knowledge is out there of how to train and prepare in order to do maximum damage. There is a “gun culture,” the internet, and easy access to everything they need.

And—BOOM, a few of them go off.

Solutions? Well, again, they come in two flavors. End the pathology and/or make it harder to be really lethal. So, less access to the most lethal weapons, or stop treating people like shit.

People who are happy, have people they love and are optimistic about their future, outside of war, do not go on mass killing sprees. Does not happen. Provide a society where people know that one slip up or bad bounce doesn’t mean social, economic, and possibly literal death; a society where people are happy, and optimistic, and don’t have to put up with bad bosses because they don’t need to keep a specific job, because they can always support themselves, and there’ll be a lot less mass shootings, suicides, and drug addicts.

Lot nicer society to live in, too. Might have to give up having as many billionaires, though. I’m sure there are a few people who will miss them, but really, having to kneel or bend over for billionaires to make a good living gets old fast and they aren’t needed for a good economy. The 50 and 60s had far fewer really rich people and were a lot better.

Final word. I had my first gun when I was 12. I grew up with hunters. I’m not “anti-gun.” But no one I knew ever felt the need to own an assault rifle. Most didn’t even own any handguns: hunting rifles and shotguns. Rural people need guns. They don’t need guns designed to kill people, unless the society is pathological. And if it is, perhaps you should make it less pathological?

It isn’t, actually, that complicated to do so. Your great-great grandparents and great-grandparents did it during the Great Depression and World War II. If they can, you (we) should be able to.

Perhaps get on that, rather than arguing about whether or not a teacher with a gun, barricaded in a classroom, can hold off a shooter. Because when it gets to that debate, your society is in the shitter.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.