Is a society prosperous when everyone has an abundance of goods, the usual definition of prosperity? Are you prosperous if you have an abundance of goods, but no time to enjoy them? Are you prosperous if you have an abundance of goods, but you’re sick? Are you prosperous if you have an abundance of goods, but you live in an oppressive society? Are you prosperous if you have an abundance of goods but are desperately unhappy and feel you’ve wasted your life?

This falls flat: more goods don’t necessarily make us better off, nor more services. More foods that make us sick aren’t better. More health care doesn’t mean we’re healthier, it often means we’re sicker. More prisons mean our society is producing more criminals and more crime.

Just increasing economic activity doesn’t make people better off. It doesn’t increase prosperity.

Perhaps the best example is the change from hunting and gathering to agriculture. It would seem self-evident that learning how to grow more food would make us better off. In fact, however, moving from hunting and gathering to agriculture lead to worse lives for most people. People were shorter in most agricultural societies, which indicates worse nutrition. They suffered more from disease and had far more chronic health conditions. Most people also had less free time and didn’t live as long as the hunter-gatherers who preceded them.

Nor was this a short term decline, it lasted for thousands of years. Height is a good measure of nutrition, and we are still not as tall as our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Pelvic depth, which measures how easily women give birth has never recovered. Median lifespan was not higher for around 6,000 years. And even after it recovered, it declined again in large parts of the world. Members of the Hellenic world, from 300 BC to 120 AD, had longer lives than westerners before the 20th century.(1)

Our lives can get worse, and stay worse, for hundreds or thousands of years, despite having more goods.

If prosperity means having more stuff, but being sicker and dying sooner, do we want it?

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing and want more of it, please consider donating.)

A better definition of prosperity is about having, not more goods and services, but the right goods and services in the right quantity.

We should want goods and services that make us healthier, happier, smarter, more able to do great works and to live well. Instead of more work, we should want right work, enough work to make the right stuff, but not so much work we have no time for our loved ones, friends and doing the activities we love, whatever those might be. And, as much as possible we should want health instead of medicine and low crime rather than prisons.

All other things being equal more productive capacity is better. The more stuff we can make, in theory, the better off we’ll be. But in practice, it doesn’t always work that way.

Part of the problem is due to hierarchies and inequality. Inequality is undeniably bad for us. The more unequal your society is, the lower the median lifespan. The more unequal the society, the sicker, in general. More heart attacks, much more stress. The more unequal, the more crime. These links are robust.

The links run two ways. On the one hand, humans find inequality stressful. The human body, if subject to long term stress, becomes unhealthy and far more likely to be sick. People who feel unequal act less capable than those who feel equal. This is true for the rich and powerful in unequal societies and the poor. Everyone suffers. Though the poor and weak do suffer more, even the rich and powerful would be healthier and live longer in equal societies, most likely simply due to the stress effect.(2)

The second part is distribution, or rather, the question of who gets to decide the distribution. The more unequal a society, the less stuff the poor and middle class have, comparatively. Some technologies tend to lead to more inequality, some tend to lead to more equality. In most hunter-gatherer societies there isn’t enough surplus to support a class of rich powerful people and their servitors, in particular their servitors who enforce the status quo through ideology or violence. With little surplus, there is equality. This doesn’t mean hunter-gatherers live badly, most of them seem to have spent a lot less time producing what they needed than we do, they certainly didn’t work 40 hour weeks, or 60 hour weeks, closer to 20. (3) The rest of the time they could dance, create art, make love, socialize, make music or whatever else they enjoyed.

Agriculture didn’t lead immediately to inequality, the original agricultural societies appear to have been quite equal, probably even more so than the late hunter-gatherer societies that preceded them. But increasing surpluses and the need for coordination which arose, especially in hydraulic civilizations (civilizations based around irrigation which is labor intensive and require specialists) led to the rise of inequality. The pharoahs created great monuments, but their subjects did not live nearly as well as hunter-gatherers.

The organization of violence, and the technology behind it is also a factor. It is not an accident that classical Greece had democracy in many cities, nor that it extended only to males who could fight and not women or non-fighting males. It is not an accident that Rome had citizenship classes based on what equipment soldiers could afford: the Equestrian class was named that because they could take a horse to war. It is not an accident that the Swiss Cantons, where men fought in pike formation, were democratic for their time. Nor is it an accident that universal suffrage arose in the age of mass conscription.

When Rome moved away from citizen conscription to a professional army it soon lost its liberty. As we move away from mass armies it is notable that while we haven’t lost the vote, formally, the vote seems to matter less and less as politicians more and more do what they want no matter what the electorate might want.

Power matters for prosperity, the more evenly power is spread, the more likely a society is to be prosperous, for no small factions can engage in policies which are helpful to them, but broadly harmful to everyone else. Likewise widespread demand, absent supply bottlenecks, leads to widespread prosperity as well.

In the current era we have seen a massive increase in CEO and executive pay, this is due to the fact that they have taken power over the primary productive organizations in our society: corporations. The owners of most corporations, if they are not also the managers, are largely powerless against the management. It is not that management is more competent than it was 40 years ago, at least at their ostensible job of enriching shareholders, it is that they are more powerful than they were 40 years ago, compared to shareholders and compared to government.

Because increases in the amount we can create do not automatically translate into either creating what is good for us, or into relatively even distribution of what we create, increases in the amount we can create do not always lead to prosperity, and certainly they do not have to lead to widespread affluence. Productivity in America rose 80.4% from 1973 to 2011, but median real wages rose only 10.2% and median male wages rose 0.1%.(4) This was not the case from 1948 to 1973, when wages rose as fast as productivity.

Increases in productivity, in our ability to make more stuff, only lead to prosperity and affluence if we are both making the right stuff, and we are actually distributing that stuff widely. If a small group of individuals are able to skim off most of the surplus then prosperity does not result and if a society which is prosperous allows an oligarchy, nobility or aristocracy to form, even if such an aristocracy (like our own) pretends it does not exist, society will find its prosperity fading.

Creating goods that hurt people is not prosperity either. At the current time about 40% of all deaths are caused by pollution or malnutrition.(5) If someone you love has died, there is a good chance they died because we make stuff in ways that pollute the environment, or because the stuff we make, like much food, is very bad for us. Being fat is not healthy, and we have an epidemic of obesity. Even when we do not, immediately, die, we suffer from chronic diseases at a rate that would astonish our ancestors. As of the year 2000, for example, approximately 45% of the US population suffered from a chronic disease. 21% had multiple conditions.(6) Some of this is just due to living longer, but much of it is due to the food we eat, the stress our jobs inflict on us, and the pollution we spew into the air, land and water.

We should always remember this. Increases in productive capacity and technological advancement do not always lead to welfare and when they do, they do not have to do so immediately. The industrial revolution certainly did lead to increased human welfare, but if you were of the generations thrown off the land and made to work in the early factories, often 6 1/2 days a week, in horrible conditions, you would not have thought so. You were in virtually every way worse off than before being thrown off the land, and so were your children. A few industrialists and the people around them certainly did very well, but that is not prosperity, nor is it affluence.

Prosperity, in the end, is as much about power and politics as it is about technology and productive ability. The ability to make more does not ensure we are making the right things, or that the people who need them, get them. Productive capacity which is not shared is not prosperity.

Originally Published Jan 31, 2014.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

Something is moral if it is good for people you know. Something is ethical if it is good for people you don’t know.

Something is moral if it is good for people you know. Something is ethical if it is good for people you don’t know.

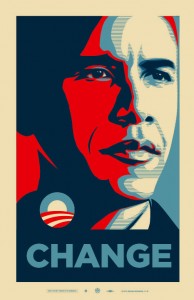

I want to revisit this. Obama was the last person who had a real chance to change and fix things. A crisis is an opportunity. FDR used the Great Depression to change the US. Reagan used stagflation to change the US. Bush used 9/11 to change the US.

I want to revisit this. Obama was the last person who had a real chance to change and fix things. A crisis is an opportunity. FDR used the Great Depression to change the US. Reagan used stagflation to change the US. Bush used 9/11 to change the US.