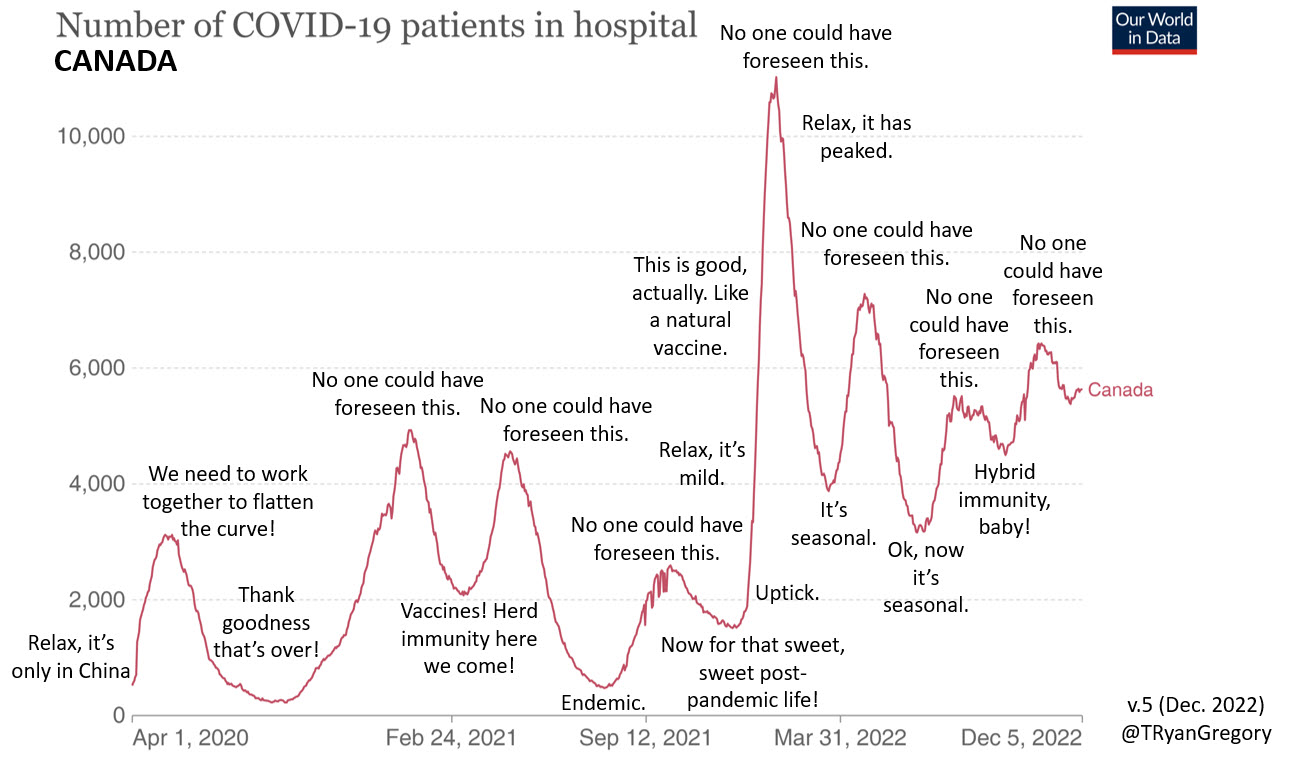

Covid will not miraculously end. New variants will continue to be born, and they will generally be optimized for immune escape and damage. Hospitals in most countries will continue to be under high strain, because governments will keep pretending Covid is over when it is not and that it doesn’t ravage people’s immune systems. I find this chart of Canada’s Covid experience applies to most countries in spirit.

This will likely be the warmest year on record, but the coldest year of the rest of your life and if it isn’t, it’ll be in the top 5 on both lists. Same with extreme weather events. These will combine with water shortages to cause more problems with the food chain and there will be serious food price fluctuations, though how serious will depend on where you live and who gets hit hardest by climate events. Frequency and severity are increasing, but predicting exactly what where is in most cases impossible, which is part of the problem.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write next year. If you value my writing and want more of it, please consider donating.)

Nothing of significance will be done about climate change or ecological collapse, though some agreements may be signed which will have no teeth and no noticeable effects on the top line numbers.

The US will continue to pile sanctions on China in an attempt to stop it from challenging the US. Those sanctions will be damaging in the short run, but nothing the US sanctions will be something China can’t genuinely learn to make themselves because they aren’t racially or culturally inferior, and they have the largest industrial base in the world.

Cold War will continue to develop, with the BRICS at the heart of the other side, and movement towards an alternate financial system which bypasses the dollar will likewise continue. China will not allow Russia to be strangled by Western sanctions. Countries outside the developed core will continue to sway towards China, which offers cheaper loans and goods and is their primary trade partner, and also, with a few exceptions, interferes less in their internal politics.

A continued movement towards vertical integration in companies and to countries trying to be able to produce more of their own key goods. People are figuring out that as the cold war develops and neoliberalism collapses, you can’t, actually, trust the supply chain and the poorer you are, or the more the US dislikes you, the more that is true. This will play into countries choosing sides, as well. China does produce more of what most countries need than the US does now and that is going to become more, not less, true, especially when you add in Russia.

Europe will continue to lose industry to America and other low-energy cost nations. I rather doubt they’ll prioritize protecting their industrial base over being American satrapies and anti-Russia, so the EU’s decline as a great power will continue even as they militarize under US guidance and control, using US weapon systems and thus making their dependence higher.

I’d like to be wrong about this one and there’s a small chance I might be, since as the economic consequences become worse, the population may become desperate enough to realize that the cost to anti-Russianism may be a bit too high.

Join in with your dead-obvious predictions in the comments. The best way to be right about things is just to accept the blindingly obvious. Oddly, most people are really bad at that.