The Tiller family has announced that it is closing Dr. Tiller’s clinic. The terrorists have won, and that assassination has succeeded in doing what it was meant to do. I’m sure the murderer is very happy tonight.

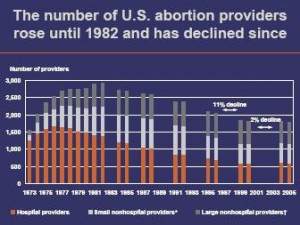

The bottom line on right wing terrorism against abortion rights is that it’s succeeding and has been for some time. Take a good hard look at the chart at the top and try and tell me otherwise. And when it comes to late term abortions, well, Tiller was one of the very few who still provided the service. According to Tiller, speaking in March before his assassination, he was one of only three doctors left in the US doing such abortions. Now there are two. If those numbers are right, one third of all abortion doctors doing these abortions were just killed.

In the aftermath of Tiller’s death, I heard a lot of progressives talking about how the anti-abortion folks were losing. The bottom line is that they’re winning. It is harder to get abortions than it was 5 years ago, or 10 years ago, or 25 years ago. Abortion access peaked in 1982 and has been declining ever since. Consider that the US population has increased by approximately 30% since 1982. At the same time the number of providers has dropped by over a third.

Now, most types of abortion violence had been in a slow, long term decline (the exception is burglary) so there’s certainly some reason for optimism. At the same time I strongly suspect that anti-abortion violence will rise, along with other types of right wing terrorism, during Obama’s administration.

The larger point is simpler. It’s harder to get an abortion than it has ever been since Roe vs. Wade, because there are just less doctors who perform abortions. Until more doctors step up and start providing abortions, especially late term abortions, this will continue. It’s hard to blame doctors for not being willing to provide abortions. Not only could you be killed for doing so, your family will be stalked and perhaps harmed, your clinic will be burglarized, you will be subject to constant legal harassment and your life will, in general, be made a living hell along with the lives of your family, friends and associates.

It’s a lot to ask of someone. But this comes back to the truth of rights. You have no rights that people aren’t willing to suffer and die for. Rights that someone won’t put their life on the line for will be taken away by people who are willing to resort to intimidation, violence and to push for laws which take those rights away.

So the questions, then are these:

1) Where are the doctors who are willing to risk their lives, the lives of their families, and to endure constant harassment to ensure that women keep this right, not just in theory, but in practice?

2) Where are the mass of people who will provide money, aid, and physical protection to the doctors who put their lives on the line? Yes, they exist even now, but obviously there aren’t enough of them, because the number of abortion providers keeps going down.

Is this a right you’re willing to risk your life to keep? If enough people don’t answer that question yes, then you will continue to lose it.