And thinking otherwise is tiresome and delusional. From Nature:

Young Chinese scientists who got their PhDs overseas and returned to China as part of a state-run talent drive published more papers after their return than did their peers who stayed abroad. The productivity bump can be explained by returnees’ access to greater funding and an abundant research workforce, according to the authors of an analysis published in Science1. The findings come as geopolitical competition between the United States and China mounts.

The only things which could derail this are a major war which China loses (though no one’s likely to “win”), or being disproportionately effected by climate change and ecological collapse and unable to handle it.

As regular readers are probably tired of me saying, this happened before with the UK and the US. The research center moves to the manufacturing base.

Meanwhile, a study found that “disruptive science” has declined.

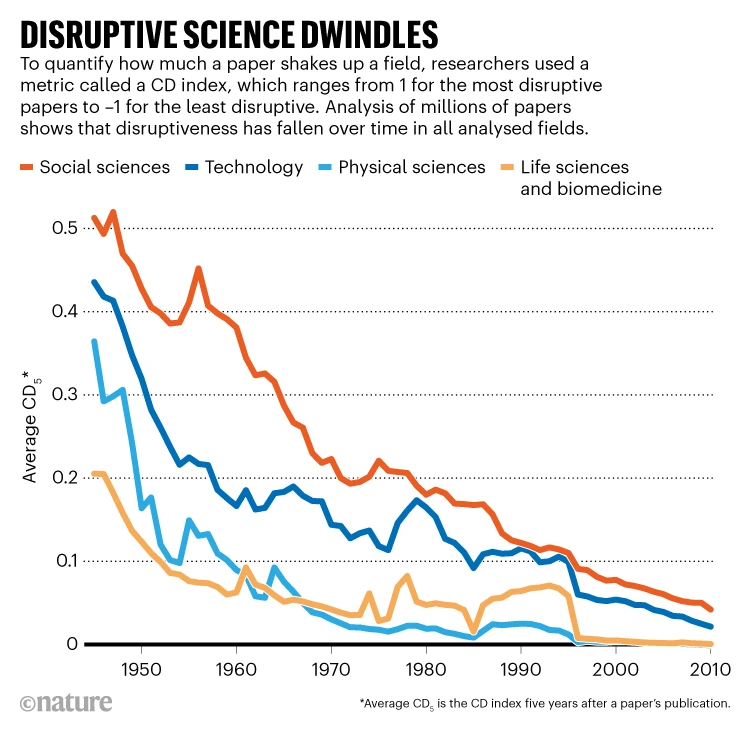

The number of science and technology research papers published has skyrocketed over the past few decades — but the ‘disruptiveness’ of those papers has dropped, according to an analysis of how radically papers depart from the previous literature1.

Data from millions of manuscripts show that, compared with mid-twentieth-century research, that done in the 2000s was much more likely to push science forward incrementally than to veer off in a new direction and render previous work obsolete. Analysis of patents from 1976 to 2010 showed the same trend.

A chart is instructive:

Study authors suggest the following:

The trend might stem in part from changes in the scientific enterprise. For example, there are now many more researchers than in the 1940s, which has created a more competitive environment and raised the stakes to publish research and seek patents. That, in turn, has changed the incentives for how researchers go about their work. Large research teams, for example, have become more common, and Wang and his colleagues have found3 that big teams are more likely to produce incremental than disruptive science.

Finding an explanation for the decline won’t be easy, Walsh says. Although the proportion of disruptive research dropped significantly between 1945 and 2010, the number of highly disruptive studies has remained about the same.

David Graeber had another (partial) explanation:

“There was a time when academia was society’s refuge for the eccentric, brilliant, and impractical. No longer. It is now the domain of professional self-marketers”

I’m fairly sure this is a matter of institutionalization and the wrong style of professionalization. Institutions stifle creativity in most cases. Exceptions like Bell Labs are rare; unicorns in modern parlance.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write next year. If you value my writing and want more of it, please consider donating.)

The old German academic system which took over the world was extremely productive: to become a “doctor” you had to produce new knowledge. It worked fine until the massive expansion of universities after the war. I’m not an academic insider, but I’m virtually certain that the current system would be unrecognizable to those professors and scientists from the 19th and early 20th centuries: similar to the Roman Empire keeping for the forms of the Republic and pretending the Senate mattered and so on.

The other issue is that “disruptive” isn’t the same as “paradigm changing”, it’s one step down, and I’m guessing that paradigm changing discoveries have genuinely declined. We are mining the same coal seams, and have been for a long time. Quantum mechanics was discovered pre-war, the structure of DNA briefly after the war, Von Neuman and Turing Machines date from the same period. The basis of semiconductors were discovered in 47/48, and so on.

We’re mostly living off the legacy of a past civilization now (because yes, the civilization of the late 19th and early to mid 20th centuries are dead). We haven’t made a lot of fundamental discoveries since, or if we have they haven’t been followed up. Even really fantastic stuff like quantum computing is mining that same vein discovered a century ago.

Further, we have refused to really change our physical plant, beyond the widespread telecom/computer revolution. If time-traveled to the present from 1960, once you learned how to use smartphones/computers/payment systems, you’d be fine and fit in. Oh, there are plenty of small changes, I remember the 70s well enough to know that, but the basic structure is the same.

Physical plant changes demand new solutions, but we’re still running on hydrocarbons and even our “alternative energy” is old. Solar panels were invented in 1883. Windmills are ancient and windmills producing electricity are essentially as old as electricity itself. Our advances in batteries are impressive, but they are extensions.

We don’t really want to change anything fundamental. Computers and telecom were adopted wholesale not because they improve productivity (it doesn’t show up in the macro data), but because they allowed people in charge more control. But in the face of known catastrophes we have done essentially nothing.

When we decide to make fundamental changes to our physical plant and to our institutions (including universities) then there will be a massive upsurge in “disruptive science” and there will be new paradigmatic changes and discoveries, assuming we don’t wind up in a Dark Age.

That will happen when civilization collapse makes maintaining the shell of a 70 year old way of life impossible.

Donate or Subscribe To My 2022 Fundraiser