Water. As I’ve said for many years.

The world is facing an imminent water crisis, with demand expected to outstrip the supply of fresh water by 40 percent by the end of this decade, experts have said on the eve of a crucial UN water summit.

I’ll use the US as an example, though this going to effect almost all countries, some much worse than others, and it will cause a number of wars. Candidates include all nations along the Nile River, and all nations around the Himalayan plateau, among many others. The US may threaten war with Canada to get Canada’s water resources and may invade if Canada is recalcitrant. The Great Lakes will be a great problem.

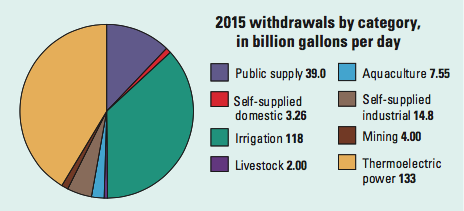

But let’s take a look at the (more or less) current situation. These are the 2015 numbers for fresh water withdrawals (numbers are done every 5 years, but I, at least, can’t find the 2020 numbers. There won’t be a dramatic change, however.)

The first thing we notice is that electricity generation and agriculture, for crops, no animals, are the big users. Public supply is a distant third with industrial an even more distant fourth.

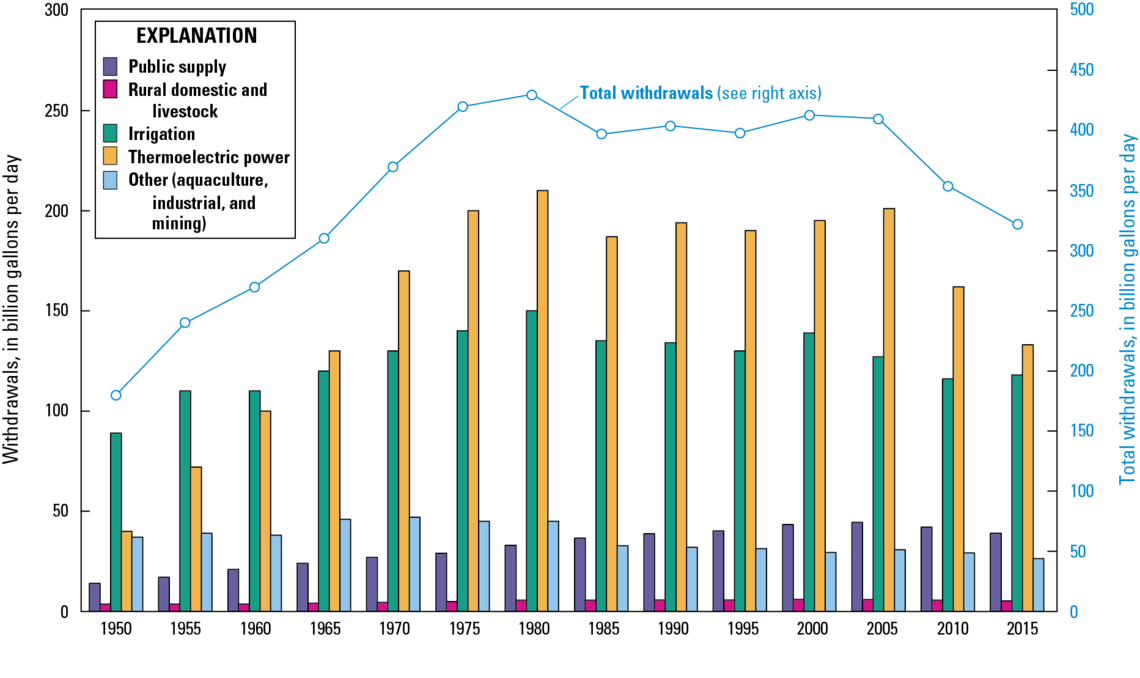

How is this historically? The news is mostly good, except in irrigation:

But the irrigation news is bad. It’s only a 2% increase, but…

Not every sector posted declines, though. Fresh groundwater withdrawals increased by 8 percent compared to 2010. And irrigation increased by 2 percent.

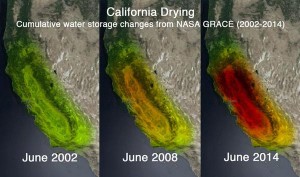

Again, the California drought effect is to blame. Irrigation accounts for 70 percent of fresh groundwater withdrawals. Rivers and reservoirs were so depleted during the drought that California farmers pumped and pumped from aquifers. Fresh groundwater withdrawals in California for irrigation increased by 60 percent, while surface water withdrawals for irrigation in the state decreased by 64 percent.

Withdrawing from groundwater means that there’s not enough rain. The long California drought, finally broken this year, but very likely to return, leads to taking more water from aquifers than can be recharged and damages aquifers so that their maximum capacity is permanently reduced.

Let’s flip back to energy generation. Thermoelectric means coal and gas and oil turbines, mostly. There is a general move away, but not quickly enough.

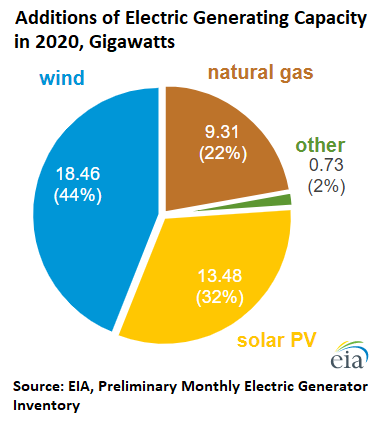

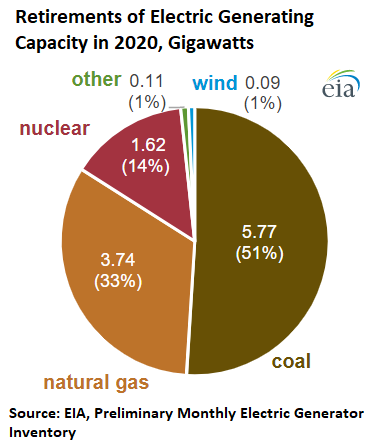

That’s the new generation added, here’s the retired.

Notice that the natural gas added (9.31) is almost equal to the natural gas and coal removed (9.51). Natural gas uses less water than coal, but still plenty.

The pace of reduction of use of water needs to increase significantly. Solar, while it doesn’t use water for generation does use a lot of water in construction, so wind is preferable from this point of view, with the standard issue of difficulty in supplying baseline energy, since the wind is rarely completely reliable.

There are solutions in many places. California is a huge water problem in the US, but desalinization could provide much of the solution since California is on the coast. I’ll do a full article on that later, but despite high costs, large scale desalinization is possible especially if it done using tidal power and not thermoelectric.

And tidal power is one of the most promising new powers. Wind and solar are unsuited for steady baseline generation, but in places close to the ocean, the waves are constant. For example:

As a newer technology this is still expensive, but moving to scale would reduce costs significantly. It’s 24 hour, though there’s variation in energy generation due to tidal cycles, it’s obviously renewable and it doesn’t use up water during generation, while it doesn’t have nuclear’s downides.

The great problem with desalinization is simply getting it from the shore inland. Depending on geography that may be doable, or not, but great waterworks programs were done in the 18th and 19th century, and much is possible.

Still, as with everything else, we needed to moving on solutions 20 years, or more, ago, and that means solutions aren’tgoing to be ready at the necessary scale in time.

One thing to take from all this, however, is that your person water use isn’t all that important. This doesn’t mean some ridiculous usages shouldn’t end: lawns should be illegal anywhere that doesn’t have enough yearlong rainfall to support them without watering, for example, but taking a shower isn’t going to kill the budget. And as for agriculture, while we can increase water thru desalinization, California growing mass crops of almonds, notoriously water-thirsty, is and always has been ridiculous. Switching to crops that need less water is a no-brainer, though it may require price supports and agricultural market restructuring.

But let’s take it as a given that there’s going to be a worldwide freshwater crisis. Even with use reductions and desalinization, rivers that are fed by glaciers and snowpacks are going to experience a decline and some will stop existing entirely. This will effect all the countries around the Himalayas, all the glacier fed rivers of North and South America, water outflow from the Corderillas, etc, etc…

At first, in most cases, there will be an increase in water, because of faster glacier melt and old snowpacks which have been essentially permanent melting. Then there will be a long term decrease, which will not be reversed without some form of global cooling, which will probably require geo-engineering.

On the bright side, increased warming will, globally, likely increase rainfall, but that doesn’t mean it will increase rainfall where you are or where crops are, and the general prospect for growing crops under global warming scenarios is dismal, except in certain farther north and south areas. Overall, however, the gains will be vastly outstripped by the losses and if we see, for example, problems with any of the great monsoons, the effects will be catrastrophic.

This will be exacerbated by the fact that aquifers worldwide have been massively depleted and the depletion continues. This is as true in India and China as it is in the US. Entire regions which rely on groundwater will collapse.

A water crisis thus feeds directly into a food cris.

As an individual there are solutions. Rainwater collection, condensers, creating your own storage spaces (common in the 20th century but illegal in most municipalities today) and so on. These will be made more difficult because of widespread pollution. It’s no longer safe, for the first time in human history, to just drink rain-water, for example and figuring out how to make the water you collect safe will be a major issue.

But you should consider doing some research on this (and I will likely revisit it with more details). You can survive 30 to 40 days or even more without food. Without water you die quick.

And, politically speaking, any country or region where the water is privately owned needs to move to public ownership.

If you think food riots are bad, water-riots will be worse and quite justifiably so.

The future is getting very close to being today.

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.