Capitalism has a lot of problems, a lot of ways it can go wrong. But power accumulation is baked in. Capitalism is the centralization of capital in a few private hands. This is justified in the ideological literature (mostly economics), because it allows for scale, and thus economies of scale, and allows for development. If capital doesn’t accumulate in a few hands it is hard to build factories, huge mines, and so on. (This is the theory, there are obviously other ways to do large scale tasks.)

Now, power accumulation is a problem in all systems. You need some to get things done, but doing too much always leads to dysfunction.

In capitalism, money controls capital (labor, land, resources, etc.). That’s what makes it different from communism, feudalism, despotism, or centralized monarchy. This is so true that the pre-conditions for capitalism include being able to buy labor and land and resources with money. This is because in, say, feudalism, you can’t — in feudalism, people mostly aren’t for hire, land is controlled by nobility and clergy, and free farmers who don’t (and in many cases can’t) sell much.

Money, in a capitalist system, is power. Power is the ability to decide what other people do. At the lowest level, this is known as demand. If you buy a chicken, it sends a signal to someone to keep producing chickens. If more chickens are bought, it says “breed more chickens.” If you’re an ordinary individual, you have this power only in aggregate.

The more money you have, the more demand you control, but you also gain the ability to not just signal; you can rent people to work for you, and they’ll do what you say.

At a certain point, you gain political power because you can hire people to influence politicians, or give them things they want, or help them get elected, and pretty soon they tend to do what you want.

The problem is that capitalism is a money accumulation system. Unless the tendency is carefully checked, money flows to the top, and so does power. Whatever secondary system is in control, be it representational democracy or the CCP, they stop making decisions based on democratic or party principles and start making them based on money.

But capitalism, to the extent it works, works because of good price signaling and semi-competitive markets. For markets to deliver, no one must have market power except a government which is acting out of motives other than profit motives.

Competitive markets are dynamic: it’s hard to keep your money over the long term, let alone for you children and grandchildren, who did nothing to deserve it, to keep it.

So capitalists on winning want to change the rules so that markets aren’t competitive.

They also want to expand capitalism into areas it should not control: roughly anything that is a natural monopoly (all of which should be run by government) or a fundamental welfare service (health, education, etc…) or which runs better when vastly dispersed.

So capitalism becomes a cancer: not only does it grow further than it should, it destroys the proper functioning of markets and of anything else it takes over which should never be part of capitalism.

The further effect is a fairly simple mechanical one: the more money is concentrated, the weaker is demand for non-luxury, non-investment goods. Back in the 2010s people were crowing about how low inflation was, but it wasn’t: the price of arts, collectibles, yachts, real-estate and so on soared: all the things rich people want. This causes general demand collapses which lead to recessions and eventually depressions.

They also distort price signals so that what the majority of the population wants and needs is under-produced and what the elites want are over-produced.

So the general rule for capitalism is that the rich have to be kept poor, which is a specific instance of the general rule across all society types that the powerful must be kept weak if the people are to prosper.

JFK was the first post-war break: he dropped high marginal tax rates significantly. Estate, income and capital gains taxes all need to be quite high on those with the most.

As for oganizations, the corporate socialists are more or less correct. We organized control in the wrong ways: large businesses must be controlled either by their employees or by their customers, or perhaps both, with the community also having some control and a veto over destructive actions. Small business are fine in the control of a single person, large ones are not. We’ve proved that over and over again.

Every good thing about capitalism is based on keeping markets relatively competitive and keeping capitalism out of the parts of the economy it shouldn’t control (about 60% of it.) And doing that means keeping the rich poor and weak.

Folks, it’s your donations and subscriptions which make it possible for me to keep writing (since I need to eat and pay rent and the cost of both have skyrocketed) so please (if you aren’t struggling) DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

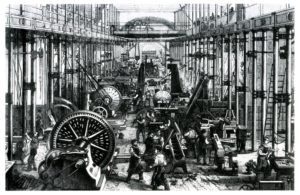

One of the most important things to understand about industrial capitalism is that the lower classes didn’t want it.

One of the most important things to understand about industrial capitalism is that the lower classes didn’t want it.