The responses to my article The Death of Capitalism made something clear:

Most people don’t know what Capitalism is.

We’ll need two definitions.

Market: An economic arrangement in which price signals direct people’s actions.

Markets are old. There were markets in Sumeria thousands of years ago. Nonetheless, Sumerian society was not Capitalist. Most people were farmers, living on the land. They produced their own housing, their own food, and their own clothes. They bought some goods on the market, sold grain on the market (there was a very active market in loans denominated in grain or silver), but most of their needs were met through non-market methods.

Some people in that society (arguably) had their lives regulated by markets. There were money-lenders, urban inhabitants, merchants and traders, specialists, and so on who used money to buy what they needed. There were other such people who were essentially feudal lackeys; you might be a market scribe working for money, or you might be a palace or temple scribe.

The primary financial markets, by the way, were run out of temples.

But the rule is this: Most people in most agricultural and pre-agricultural societies produced what they needed, generally as part of an extended family, a tribe or some other arrangement. Sumeria was more mercantile than most agricultural societies.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing, and want more of it, please consider donating.)

Capitalism: An economic system in which people are directed towards particular actions by price signals from markets AND in which they obtain the necessities (and luxuries) of life from markets.

You may measure HOW capitalist a society is by how many people cannot create their own necessities as part of a relatively small group.

Now, let us return to markets. A market says:

- Do more of what makes more money

- Do less of what makes less money

- Stop doing that which is losing money

This is an oversimplification, but it’s less of an oversimplification than it seems. Take Amazon, for example: Amazon did not make a profit for many years. However, the decision makers at Amazon (Bezos, senior exectives, etc.) made plenty of money from Amazon.

What matters is not whether fictional entities are making money, or even if all human beings are making money, but whether decision makers are making money.

Prices are not set solely by markets, they never have been and they never will be. Governments lean on prices through direct and indirect subsidies, taxes, and so on. Roads are a subsidy for trucking, auto-manufacturing and a host of other businesses, for example. The US interstate highway system was the death-knell for the hugely powerful railroads that preceded it.

This is true despite the FACT that, if you include all costs, shipping people and (especially) freight by rail is cheaper. The final price, as it effects the individual decision makers responsible for those individual, economic decisions, is what matters.

Markets are a way of telling people what to do and what not to do and how much of either.

The more money a person makes doing something, the more they try to do of that something (including hiring workers to do it for them).

If a decision maker’s profits are not aligned with social utility, well then, capitalism does not produce results with social utility. Bankers make a lot of money. Their businesses lost so much money the entire world economy could barely contain the damage and trillions of dollars were required to bail them out. So why do bankers keep doing what they were doing? Because they are still, personally, making money.

So what if a few brokerages and banks went out of business? Their executives are still rich.

Capitalism is dis-empowering. Serfs and peasants, for all we sneer at them, could support themselves, because they had access to the land they needed to do so. They spun their own clothes. They raised their own houses.

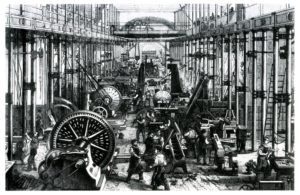

Peasants and serfs were better off than the industrial workers who replaced them. There is a reason land clearances had to be done by law and force: The peasants and serfs didn’t want to leave. They weren’t stupid, they weren’t fools–they knew they lived better than the people working six and a half days a week, ten to 12 hours a day, in the new factories amidst cities and towns, choking in their own filth before modern sewage was put in place.

Capitalism forces most people to base their decisions on price (salary, comissions, hourly wage vs. goods they buy) levels. It takes away their ability to support themselves without working for someone else.

Capitalism is the concentration of the means of production in the hands of a few people.

This is why it is called Capitalism. Capital is what allows you to make other things. Land can be capital. Machines that make things, even machines as simple as a spinning wheel, are capital. You add labor to capital and you have products.

(It may be, with the rise of the sophisticated automation we call robots, that capital will be able to make capital soon, with little to no human intervention.)

Capitalism removes productive capacity from most people so they can’t support themselves. It orders the behavior of almost everyone through price signals.

Capitalism is a way of making decisions about what people should do, what products should be created, how they should spend their time and so on.

Because Capitalism is one of two major decision making methods in our society, and has been for the most important societies (starting with Britain) for hundreds of years (in varying forms; there are different types of capitalism), it is fair to judge capitalism by the results produced by those societies, especially the economic results.

Capitalism is NOT synonymous with industrialization, but most industrialization (outside the USSR) occurred under capitalism. Capitalism made the decisions about how to industrialize which were not driven by the internal logic of industrialization itself (too big a topic to go into in this article) or by government.

Capitalism fed back into government, however, because pricing matters. That coal was cheaper than solar for most of history (until about last year) mattered. In theory, we could have overridden that decision and said, “At X times the price is worth it and the sooner we make more the sooner the price will drop,” but in practice we did not.

We went with the flow.

Social choices, including those made by government, modify market signals. But when you live in a Capitalist society, you think first about VALUE as PRICE, even though the two are very different. The price of your life can be determined very accurately by life insurance charts (future expected earnings, discounted).

I doubt you consider the insurance market’s valuation of your life as the actual value of your life. If you do? Congratulations! You have splendidly adapted to the mandates of capitalism and markets.

Having read this far, and considered what you have read, next time someone yammers on about capitalism, you will know what they should be talking about. Because most people don’t know what capitalism is, despite living in it, you will also know, perhaps, what they are not talking about.

Capitalism uses markets as the main method to determine human economic behaviour and removes humans’ ability to support themselves without engaging in the market.

Note the second characteristic listed: Removing humans’ independent means of support. In many cases, this had to be done by force. In others, it was done through blandishments. In both cases, the end result was a reduction in effective power for individuals who do not CONTROL capital–who are not capitalists (ownership is not always control).

To a remarkable extent, people are Skinnerian behavioural machines. Markets are one of the main methods used to condition people, to create their personality, to create them.

To control them.

To control you.

Under Capitalism, virtually everyone is subject to that control and conditioning, on penalty of living a miserable life, or, indeed, of death.

(This is part 2 of a semi-series. Read part one on “The Death of Capitalism” and part 3 on “Did the Industrial Revolution Require Clearances, Genocide and Imperialism.” and part 4 “How The Rational Irrationality of Capitalism Is Destroying the World”.)

If you enjoyed this article, and want me to write more, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

One of the most important things to understand about industrial capitalism is that the lower classes didn’t want it.

One of the most important things to understand about industrial capitalism is that the lower classes didn’t want it.