This is based mainly on “Crises and Decline in Credential Systems”, found in Sociology Since Midcentury, Randall Collins, 1981.

We’re currently in the late-middle stage of a higher education crisis in the West. This isn’t a worldwide crisis: the Chinese system is still in its expansion phase, but it’s very real here. Recently I was talking to a friend in Norway, who noted that most young people want a trades education and to avoid university.

I’ve noticed when discussing this that most people are resistant to the idea that this isn’t the first time it’s happened. We have this weird idea that before the modern era, there weren’t large post-secondary education sectors: that degrees and credentials from schooling are something new. This isn’t even slightly true: heck, if we had the data I’m sure we could find something similar in Ancient Egypt, and for sure the massive university systems of Buddhist India went thru more than one cycle. This before we even get to China, a civilization which was based on a credential system for something like two millennia.

But neither is it new in the West.

Schools produced standard culture (and standardized people, as far as that goes.) Culture allows the creation of longstanding institutions: not just the universities themselves, but bureaucracies of various forms, including corporate bureaucracies. It’s not an accident that companies demand degrees, especially for managers.

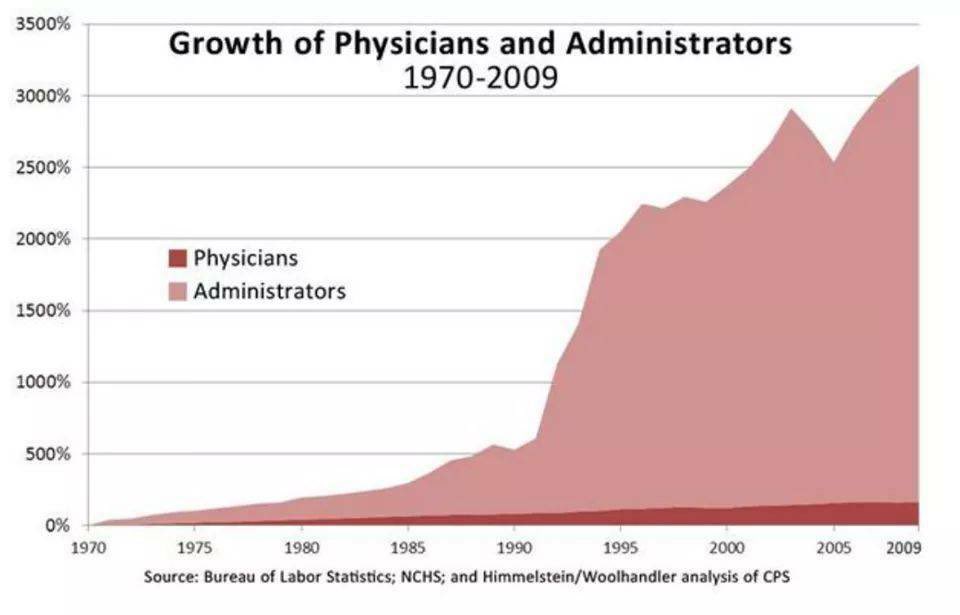

This culture creation is used in political competition. Think the medieval church vs. various kings, or the kings v.s their feudal lords, or Confucian scholar officials v.s hereditary nobility. In the modern world consider what happened when university trained, mostly Ivy league, degree holders took over the media, or the effect of MBAs taking over from engineers in companies. Boeing is a good example of the consequences, but so is the entire shipping of industry out of the US, and the enablement of China.

Education is one of the sinews of political conflict.

Universities (or credential systems in general) go thru four phases. All four don’t always happen, sometimes the cycle is stopped before it reaches its end.

Expansion. Lots of new students pour in. More institutions are created. Formal requirements for professions are credentialized thru the institutions. In the Medieval era this was civil law, canon law, medicine and theology. In the modern era it includes much more, but of particular note are engineers. During this period having a degree means an almost complete certainty of getting a job. Think of the 50s: a BA was all you needed to vault into management.

Cultural Production Outstrips Positions. An end to the easy early period. You have to compete for positions, there aren’t enough. Credential inflation starts: what once required a B.A. now requires an M.A. The amount of time for higher degrees gets longer and so on. (Back in the early 90s a friend taking a PhD in psychology told me that a PhD alone was no longer enough. Ten years earlier, it had been.) The price of getting an education increases, and in this and the third stage, it tends to skew more and more to the wealthy.

This, I note, has obviously happened in our society. Back in the sixties, education was practically free, now it requires a loan students may not pay off for decades, or ever.

All the positions are filled. (We are here.) There isn’t just a lot of competition, the degrees are increasingly worthless unless you also have clout from something other than education because the positions are filled. The number of people who live off the productive system but don’t contribute to it goes up.

This goes in phases: right now BAs get you nothing but a chance to apply and be rejected, and BA enlistment is falling, but STEM still offers a decent chance. (This won’t remain true in the West for much longer.) During this period alternate culture production really gets fired up: intellectuals who can’t get positions produce books, pamphlets, blogs, podcasts and so on. They attack academia and seek forms of legitimacy other than credentials.

Finally, collapse. The state stops enforcing monopolies, university enrollment drops and many institutions fail entirely. Other forms of cultural production become dominant.

The Medieval University Cycle

The rise really gets going in the 1100s, though some institutions are created earlier. By the 1200s they are accredited by the Church of the Holy Roman Emperor. This makes the credentials valid throughout Christendom, which no other higher credentials are. At this time both the papacy and various kings and principalities are expanding their administration, and there are tons of positions. As with the Confucian scholars in the early days, these administrators are used to expand central authority: feudalism begins its decline. In addition the monopoly of law, medicine and theology works against feudal nobles.

Every major pope from 1159 to 1303 held a degree in law from a university. One of the signs of the end of the reign of the medieval scholastics is when other ways of training come to the fore. In England in the 1400s, for example, lawyers no longer learn and OxBridge, but in London in what amounts to an apprenticeship system. By the 1500s OxBridge no longer teaches physicians, this moves to the Royal College of physicians and soon after the monopoly of clergy on medicine is ended.

The height of the system is significant: two thousand to four thousand students were enrolled at Oxford and Cambridge, for example. This is 4x as many, proportionally, as were enrolled in Elizabethan England and as a proportion of the population the medieval height wasn’t surpassed until after 1900. At this height at least five percent of the male population attended university and it could have been as high as 10%.

The medieval system, note, goes into decline fifty years before the black death: so it wasn’t caused by declining population.

As the medieval system goes into decline, the humanists rise. They work outside of universities often as publishers or authors and rely on noble patronage. They mock the old academics as rigid, fusty and out of date.

But the decline isn’t good for ordinary people: as mentioned in our own case, education becomes less and less available unless you have money and stops being a major way for people to rise. This was very much true in the medieval university decline: at the beginning many poor individuals could attend, but as time went on this became much less true.

Signposts of Decline

- smaller institutions folding. (The closure of many of the small liberal arts colleges in our time, for example.)

- a fall in the number of students.

- decline in number of institutions.

- loss of monopolies over credentials.

- widespread attacks on what is taught and how it is taught. (We see a great deal of this now, and it has progressed to politicians passing laws.)

- Increase in the cost of education, with poorer students being cut out.

- Cheap degrees which are mere formalities: degree mils and so on.

Note that phases three and four also can feed into political instability. In recent years Peter Turchin has popularized this, and many think he created the idea but it’s long been discussed as important in revolutions such as the French and Russian ones. People who are highly educated but didn’t get the positions they wanted are vastly destabilizing: they feel betrayed and they have the tools to fight ideologically and often the understanding of how to administer movements and other organizations.

Raise someone’s expectations, train them, then let them rot in poverty and you’ve made yourself a potential enemy.

These cycles are dead common. Collins identifies a number, just in the West:

- The Medieval cycle – starts in the 1100s, peaks in the 1200s, over in most places by the 1400s.

- English cycle from 1500-1860

- Spain from 1500-1850

- France 1500-1850

- Germany 1500-1850

- US 1700-1880

The various national ones, though they start at about the same time, other than in America, are separate and have different patterns of rise and decline. Not all of them go all the way: the American universities never go thru phase four, for example.

Education Systems Rise and Fall like all else in human society. What is happening now in our system is very similar to what has happened before and if we want to understand what will happen to our system, the best way to know is to see what happened before. It will never be a one-to-one match: the details will differ, but the pattern will hold.

The obvious thing to do for those who want to slow the fall and end it before collapse is to figure out what sort of training they can produce which isn’t in oversupply. For individuals the question is where the new form of cultural production is and how to legitimize it and reap the benefits of that legitimization. One might wonder if the rise of podcasting intellectuals who use their celebrity to sell their books is a fad, or a sign of something greater, for example. I may return to that in the future.

In the meantime: it’s all happened before.