A couple years ago I read “The Dawn of Eurasia” by Bruno Macaes. Macaes was a member of Portuguese government, very neoliberal and fairly awful while in office, but his book proved quite insightful in most areas outside of Russia, where what seems to be fear and contempt for Russia distorts his vision. (I thought this when I read it before the Ukraine invasion.)

He’s most worth reading about Europe and the EU, and one example and one passage particularly struck me at the time.

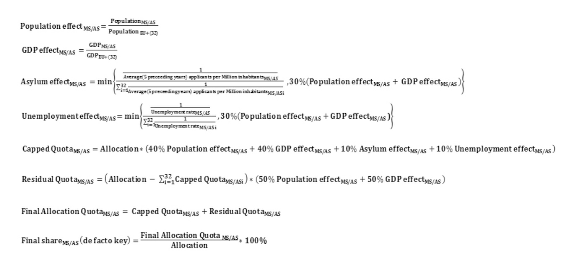

This is the formula for accepting immigrants during the refugee crisis.

Macaes writes:

I was reading the account of the meeting in my office when it suddenly hit me. The European Union is not meant to make political decisions. What it tries to do is develop a system of rules to be applied more or less autonomously to a highly complex political and social reality. Once in place, these rules can be left to operate without human intervention. Of course, the system will need regular and periodic maintenance, much like a robot needs repair, but the point is to create a system of rules that can work on their own. We have entered the end of history in the sense that the repetitive and routine application of a system of rules will have replaced human decision.

Maçães, Bruno. The Dawn of Eurasia (p. 228). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Weber famously called bureaucratization an iron cage: rule by rules and not people, everyone in the same circumstance was supposed to be treated the same, and who the bureaucrat was didn’t matter: once the rules (in modern terms, the algo) had been set up, the human was just a piece of machinery.

It’s for this reason that technocrats love computers and algorithms so much; they make it almost impossible for ordinary humans to override the rules.

Many years ago I moved from Ontario to BC. My Ontario health care coverage was ended. I applied for BC coverage, but then, unexpectedly, I returned to Ontario. I had no coverage. I went to the provincial health office in person, told the person at the desk, they summoned their boss and it was explained to me that there was a six month wait, but they would fix it.

How? The only way was to finangle the system so it thought I had never stopped having Ontario coverage. There was no human discretion, just a flaw in the system which allowed them to do something they really shouldn’t have done. (This is over 30 years ago now, which is why I feel free to mention it.)

If they hadn’t, I’d have had no coverage anywhere in Canada and I was extremely sick and needed health care right away. (Which is probably why they did jiggle the system.)

The idea of bureaucratization was a good one: previous to that offices had been filled by people with a great deal of latitude, which many of them abused to help their friends and family and to enrich themselves. Even when they didn’t abuse the office, they were inconsistent, and no one knew what the rules really were and thus couldn’t plan. As Weber points out repeatedly, you need calculable law and administration to allow modern capitalism. Decisions don’t necessarily have to be good, but they do have to be consistent, or you can’t plan and one unexpected decision can destroy your business.

We moderns will note that the promise of bureaucratization hasn’t really worked out: it’s been subverted. The rules are made and somehow they always favor the rich.

The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.

—Anatole France

Now, the law has always favored the rich, but the idea of bureaucracy combined with democracy was that it would do less of that. In some time periods it did, and does, but in most all it did was change the type of rich it favored, moving from aristocrats and clergy, to oligarchs.

The EU, however, firmly believes in bureaucratization, as Macaes notes. It is what is good. The rules exist, they are followed, humans intervene only to set up the rules and occasionally tweak them, but otherwise it’s a big machine algo, and it runs like that. If it hurts or harms someone, so be it, it is fair, because the rules are being followed.

Macaes has a lovely little anecdote about Brexit and immigration which highlights the issues:

I particularly remember a conversation in Manchester with Ed Llewellyn, David Cameron’s chief of staff, where we tested different ways to reduce immigration numbers, some of them quite feasible. This was during the renegotiation process leading up to the referendum. Llewellyn seemed hopeful for a moment, but then shook his head: ‘These are ways to reduce the numbers. What we need are ways to increase the feeling of control.’

Maçães, Bruno. The Dawn of Eurasia (pp. 231-232). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

What the Brits wanted, in other words, was to have humans regularly making decisions, rather than one algo set up by a committee making the decisions, even if the algo was more favorable to them. Basically, can the Prime Minister or the Home Secretary decide how many immigrants come in? No? Then forget it.

It seems to me that the algo-ing of government, the bureaucratization, is a good thing up to a point: people should be treated about the same in the same circumstances. But as a practical matter, bureaucratization, the iron cage, is used to elude responsibility. “The algo did it!” or, “That’s what the law says!”

Every algo was created by people, and while there are sometimes unforseen effects, what the algo does is the responsibility of people. If it is producing injustice, or poverty, or massive inequality those who created it, or those who are letting it run are responsible.

The more you hard-code an algo, and take people out of its implementation, or create systems which force people to become machines unable to make exceptions, the more the dead hand of the past rules the future, and the more that the few people at the top rule everyone else. When middle and low level bureaucrats can’t actually make decisions, injustice inevitably occurs because virtually ever law or algo has blind spots: events and circumstances it did not and cannot deal with.

The evil of three strikes laws and mandatory sentencing, for example, was meant to prevent the evil of judges using their judgment to let people people off if there were mitigating circumstances. Sometimes that discretion was misused, and it would be a big story, but even more often there would be a case of someone’s third crime being stealing a bicycle or a banana.

The ultimate problem is that there’s no getting away from the fact that humans have to make decisions about humans lives. Even if we wound up in a Wall-E world, served by machines, those machines’ initial programing would have been created by humans.

The principles that exceptions need to be made and that humans need to have some control, and that over-bureaucratization removes low and middle level control don’t change the idea that people should be treated equally in the same circumstances. Provincial laws didn’t intend for any Canadian to not be covered by some provincial health care plan; the algo; the rules, had a gap, and a low level bureaucrat could make it work, at least back in the early 90s (today, who knows?)

The same is true at higher levels. There is no escape from human judgment. Attempts to bind everyone with trade deals which are immune to popular sovereignty; with treaties, and to have secret courts and central banks and so on, are all ways to try to avoid responsibility for results.

The problem with our societies is that elites aren’t held responsible for the harm they cause, nor, by and large for any good they do. We have elections without being democratic, because the feedback systems are broken.

All that has happened with bureaucratization, is that the rich still get taken care of, and the poor still get fucked, and it’s done in a way that seems “fair”.

“The algo said” is just a modern version of the “the law says” and it’s just a way to disempower almost everyone while making sure power and money are concentrated at the top.

Any algo or law which doesn’t allow for human discretion to override the algo, with a review mechanism for people who do it often, will do more evil and prove more anti-democratic than even venal spoils systems, which at least don’t pretend that office-holders and other powerful people don’t make decisions and aren’t responsible for their results.

Astrid

Pity we can’t land arkships in Belgium and Washington DC, and tell the local PMC (and telephone sanitizers) that their help is urgently needed to revalue the price of rocks on the moon and keep their phones sanitary.

I suppose one day these abstract expressionist will hit the hard wall of no food, no fuel, and no way to spend their fiat currency and IP squatting rights. But what will happen to humanity and biosphere in the mean time?

bruce wilder

I have heard Jordan Peterson make a point about the distribution of scores on so-called IQ tests. Peterson — my appreciation — is sometimes quite impressive, but almost always ruins what he says (for me) by being a reactionary jerk, repeating conservative shibboleths. And, this was one of those times, in a telling way.

As you may know, scores on Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests are, by convention, normalized so that overall population putatively being tested (the imagined universe of the tested) has an average normalized score of exactly 100 with a normal distribtion, standard deviation 15. So, two-thirds of the whole population when tested will score between 85 and 115 and 95% of the population will score between 70 and 130. Only 2.5% will score above 130 on this normalized scale. The “Quotient” comes in because IQ tests are traditionally also normalized for age, so 100 for eight-year-olds, say, is a lower raw score than for an adult.

There are all kinds of technical problems with any actual particular test instrument as well as with the normalizing of scores for a specific test applied to a specific subset of the population, not a large “random” draw from the whole population of adults. And, of course, there are profound questions about what exactly an IQ test tests. On such technical questions an accomplished academic like Peterson can be facile and dismissive in his rhetoric.

The point I want to make isn’t about the merits of IQ testing; I want to say something about the blindspots political conservatives reveal when they start talking about the “evidence” of IQ testing and how that evidence proves the rightness of their worldview.

Jordan Peterson makes the point that a normalized score below about 80 (if accurate), would indicate the test-taker is handicapped as a learner to the point of effective disability relative to navigating the modern world. He cites the U.S. military which has been administering a form of IQ test to potential recruits and draftees at least since World War I and today will simply not enlist anyone scoring below the equivalent of “80”. (I have not verified Peterson’s assertion of a U.S. Army threshold standard.) A score below “80” in the Army’s experience indicates that person cannot be economically trained for any useful role or service. Peterson extrapolates, saying this means that ~8% of the whole population can find no secure, productive place in the modern political economy.

That this is “the problem” Jordan Peterson would choose to highlight, drawn from the observation of a broad range of human ability marks him out as a reactionary jerk.

Let’s assume for the moment that IQ testing confirms what most of us already knew: that some people are smarter in some sense or another, just as some people are taller or better singers or have better eyesight. And, some people are really stupid, short, tone-deaf or blind.

What I notice in Jordan Peterson’s telling of this anecdote (is that the right term?) is how shorn of social context intelligence has become for him by having it reduced by the proxy of a test to an index number. And, the how it feeds this idea that there is a burden imposed on society by the deadweight of these dummies. He hasn’t, mind you, investigated who these people are who test out below “80”. And IQ testing is proximate if not altogether central to his academic research, so it is fair to expect him to go look into it if he thinks this is a real problem for society increasingly exacerbated by digital modernity.

I look at the distribution of intelligence and the implications of having a few clever clogs at the extreme suggests to me that the more acute problem is likely how to prevent the smart from turning society into a neo-feudal realm where the few smart manipulate the rules of the game to perpetually cheat the normies, just as a few healthy, athletic blokes with swords and armor once extracted wealth from peasant farmers, while alternately “protecting” the peasants from looting and pillage and practicing the same.

If I were a political conservative of the most usual type, I would want to ease “the burden” of bureaucratic regulation the better to cheat. I would be mad that the FDA bureaucrats had roused themselves to require that baby formula be made in a clean facility, when I could make more money with less effort if only parents would accept their own personal responsibility when my contaminated formula occasionally killed a baby — I mean didn’t they read the label where I warned that might happen for any number of reasons?!

bruce wilder

I would make several points about bureaucracy.

One is bureaucracy as an institutional tool of governance is, at base, about generating political power to facilitate technical control of economic processes. Political power flows not so much from the barrel of a gun as from the social organization of bureaucracy, which marshals knowledge and information to achieve economic outcomes.

There is useful sense in distinguishing the use of bureaucracy by governments producing and distributing public goods, including but not limited to the arbitration of disputes, from the use of bureaucracy by private enterprise financed by capitalist seeking to extract economic rents from ownership and control of the artifacts of invested (aka sunk-cost) capital.

A government seeking to effectively regulate the for-profit financial sector thru bureaucratic rule-making would, I expect, be making up a lot of simple, somewhat arbitrary, bright-line rules. Doing what the U.S. public financial regulatory establishment purports to do — put a few smart folks in charge of “supervising” “systematically important” institutions — will never work. Why? Because the smartest guys in the room have every incentive to game the system, any system. The public bureaucratic institutions, run by salaried public servants of normal intelligence and stunted greed and personal ambition will need simple, bright-line, arbitrary rules to be effective in containing cunning greed and overweening will to power. Simple rules like limiting the geographical scope of commercial banking — “no branching across state-lines” say or no stock brokers owned by banks and no insurance companies owning property appraisers. No usury, period.

This is not the same rationale as the one hidden in neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is based on an economics that babbles about the non-existent “market economy” and denies that the economy is, never mind should be, organized by bureaucrats, public and private, playing games. Neoliberalism is the art of disabling democracy and possibility of popular opposition to globalist/capitalist desiderata. The algo that never need explain itself or say, sorry, is its design goal.

Astrid

Thank you Bruce! Great discussion.

Too much about talk about intelligence goes to people near the top of the head justifying their position there, rather than creating a system that works better for everyone. The (hidden classist, because we can’t talk about class anymore) discussions about who belongs where in the pecking order is really no better than the race based justifications of the 19th century, and your argument lay a good case that in practice, it’s even worse and more insidious.

Willy

I don’t wonder what Jordan Peterson makes of Herschel Walker. I wonder what Jordan Peterson makes of the many supporters of Herschel Walker in his bid towards one of the highest offices in the land. Do they all have bottom 8% IQs? Is this part of some natural strategy for 8%ers to gain some sort of power, real or imagined? I’ll let wiser minds decide.

Way back when I was a truth-searching lost boy, a concerned parent might’ve found the dented paperbacks I’d hurled under my bed. Books from Carlos Castaneda and L.Ron Hubbard were among them. Recommended by others, their texts would always start out with practical life wisdoms which seemed deep and useful for a kid with unconcerned parents. But then these authors would wander into bafflegab so confusing and implausible that I’d finally yell out “Bullshit!” and hurl the paperback (which I’d bought with hard-earned paper route money) under the bed.

After the internet became useful I learned that those authors had simply stolen aphorisms from the actually-wise, paraphrasing them to use as bait to lure naïve young followers into a world of nonsense as part of some lucrative grift. This is how I see Jordan Peterson. Come for the wisdom, but stay for the Hershel Walker.

Speaking of lucrative bureaucracies and their aphorisms, which allow incompetents to fail upwards…

I once had this acquaintance friend who graduated from a middle American MBA school in the middle 80s along with his middling frat buddy. Thinking himself the more glamorous and promising, he went into the then more glamorous and promising field of retail rentals, while his lesser buddy went into establishment medical management. “Boring!”, the Rocky Horror crowd shouted.

Nearly four decades later, Mr Rentals was working 6 long days a week, regularly traveling hundreds of miles trying to keep up with the regional managing of dozens of retail rental branches. As an added bonus, his company kept consolidating and adding territory to him as a cost savings measure, without Mr Rentals seeing another dime.

Meanwhile, his lesser buddy was managing just one city hospital located minutes away from his own home (and birthplace even), working 9 to 5 and only on weekdays, while making five times what Mr Rentals was making.

Witness the power of the dark bureaucracy! Apparently in our late-stage capitalism, if you build it they will come. And pay. Pay 1-2% of their outrageous medical bill for the surgeon, the rest for “all the other stuff” which the algorithm says it needs. Or perhaps, has calculated that the bureaucracy it services can get away with.

I’d get into social media’s bot bureaucracies and all their devious algorithms favoring conservatives “fear and anger” over progressives “empathy”, because the former is far more lucrative, but have probably talked way too much already this go-round.

Trinity

Another great article.

And then there is the rise of AI, which seems specifically designed to make our lives even more miserable (such as when I call customer service).

“the feedback systems are broken”

I don’t think this is true, the system is working exactly as intended. The current feedback systems are the quarterly profit statements, and shareholder comments (and certain account balances, but not ours).

Whether it’s rules or AI, or bureaucracy sans humans, there are many problems I’ve identified over the years. One is the lack of or outright bad science used to determine the rules. Again, this is intended currently. But the good rules that benefited the commoners were either never intended to help the low born, or aren’t ever fixed if they eventually stop helping the unwashed, even if they cause harm.

The second is the scale of the rules, and by scale I mean the level of government at which the rules are applied or enforced, because this is a very important part of the rules that no one ever seems to question. It’s always talked about, but rarely questioned. For one (rather bad) example, Roe v. Wade should have been established at the national level, not the state level. It should have been a “universal” (all citizens) “rule”, available to anyone in need, because it applies to an individual body, same as the right to bear arms, or the requirement to register for the selective service. Or pay federal taxes. Bruce also gives a good scale example about banks above.

The third is ignoring the complex nature of societies over time. Things change, it’s the universal constant, so rules should (in a perfect world) always be fluid, and the AI is only trained to spot when a rule change is needed. We’ve watched that fluidity in play for decades now, as the rules have changed drastically compared to fifty plus years ago. And we’ve watched as other rules remain the same, even though they’ve become inappropriate in the “post modern” (post industrialization, now financialized) world.

As long as oligarchs remain in charge, and they’ve been in charge for most of the past two thousand+ years, the rules will also remain fluid only for them. The overall problem is their idea of fluidity is allowing unsustainable practices, and in fact increasingly allowing even more such practices over time. It’s this part that keeps me awake at night.

The biggest problem remains: who gets to make, and enforce the rules.

And those of us who don’t make the rules (and the climate, which makes its own rules, at the necessary scales) are the future feedback systems. I believe this to be true. It’s not much solace for the present, but a little for some unknown future.

Ibn Bob

I have come to the conclusion, after almost 50 years within bureaucracies (including writing some rules) that the quality I’ll call here “judgement” must be developed in individuals. It can be put into a summary:

Which rules can be bent; when, and how far.

Which rules can be broken, and when.

Which rules must remain written in stone.

Good bureaucrats develop judgement (which is why seniority and institutional memory can be important factors).

Essentially, to function well bureaucrats must bear in mind the rules of the system, as well as its purpose and customers, and strive always to keep them in balance.

Aurelien

The European Union has inherited a largely Franco-German model of political management, which Anglo-Saxons never really understood, even when the UK was a member. It has two particular features that are relevant here. One is that there is a fundamental distinction between the political level, where the decisions are taken, and the so-called “services” who carry orders out. The Weberian element in the EU, if you like, is the Commission, which has a powerful but limited role, in turning political decisions into rules and regulations. The Commission is a career, supranational bureaucracy, but it doesn’t make political decisions.

The other is that bureaucrats, in such a system, may only act if they have been specifically delegated certain powers. This is what is known as the “competence” doctrine, and is the opposite of the Anglo-Saxon view that government and its servants can do anything which is not specifically precluded. In the continental system, you can only act if (a) you can point to a specific competence that has been delegated to you (b) you keep exactly to the rules and (c) you can show that you have consulted and are respecting all applicable national and European legislation. Most European states (and the EU) have administrative courts, where you can get a government decision overturned if a person has exceeded their powers, or if they haven’t followed exactly the right procedures. Having worked in both systems, I tend to find the Anglo-Saxon one more congenial, but in the end it’s a matter of culture. Equally, I’ve been in countries where the rules are frequently bent, and almost always in the interests of the rich and powerful. Be careful what you wish for.

bruce wilder

@Aurelian

That’s quite insightful. In some key respects the structure of governing institutions for the EU resembles nothing so much as Bismarck’s North German Confederation and later, Empire. The British tried to master EU politics with allied client states, insisting on membership for such unlikely “states” as Malta and Cyprus. The only EU institutions that prefer French to English are the legal ones and that greatly frustrated London, even though English law continued to prevail in a few key areas affecting finance.

The superficial problem was immigration — England became the most densely populated country in Europe, surpassing the Netherlands and the Swiss plateau, but also with something like 15+ of the poorest cities in northwest Europe. (Switzerland though not an EU member is nevertheless bound by EU rules including on immigration, something that causes lots of democratic resentment.) The deep problem is that Britain is a debtor and the neoliberal EU is really not friendly to debtors, even ones with out-sized predatory FIRE sectors.

StewartM

Great post by Willy using the Herschel Walker metaphor. Jordan Peterson and his ilk fit that categorization perfectly. Use erudite language to baffle people with bullshit.

As far as Ian’s post: my quick comment is that our modern neoliberal bureaucracies don’t even function as “iron cage” bureaucracies. When the rules need to be broken for the benefit of the upper crust, by god then they’re broken. They are only iron cages for the little people. It’s why capitalism in practice never performs as it should in theory, as capitalism (as Ian notes correctly) NEEDS the state (despite what goofy libertoons think) and therefor it is in their profit-maximizing self-interest for them to capture the state, set the “rules”, and then break/ignore the rules when it’s inconvenient for them.

different clue

Perhaps in hindsight FDR should be viewed as America’s Dubcek and the New Deal should be viewed as America’ “Prague Spring”. He wanted ” Capitalism with a human face.” It lasted a while before our Brezhnevian Reactionary Overlords were able to destroy it all.

Back to closer to the subject of the post . . . . bureaucratic rules are an attempt by humans in social-insect-sized societies to create something like the predictable chemical signaling systems and rules by which millions of social insects can co-order and co-ordinate their activities. Bureaucratization is part of the social insectification of mankind, which is also known as ” civilization”.

StewartM

On Jordan Peterson’s fetish with IQ scores.

Most of us would agree that we don’t all have the same mental capabilities, just as we don’t all have the same physical strength or speed or dexterity. But the notion you can reduce mental capacities to a single, scalable, number seems just as silly an idea of doing the same with physical abilities, and assigning a single number to rank Micheal Jordan, Tom Brady, Henry Aaron, Wayne Gretsky, Eddie Merckx, Jerry Rice, Mark Spitz, Bjorn Borg, and more. It seems to me blatantly obvious that just like there’s not one type of physical abilities, but subsets of quite different skills, and the same is true of mental abilities. There are computational skills, language skills, perception skills, memory, and more.

Ché Pasa

A strong and ostensibly nonpartisan/neutral bureaucracy is essential for the operation of any large scale modern or indeed pre-modern imperial or other form of state. You simply can’t have the one without the other. This is Iron Law, found at the very outset of large-scale government.

“Neutral” is not necessarily indifferent. Nor does nonpartisan require a bureaucracy that posits itself as a primary partisan player (“The Party of Government, eg.”)

The EU’s version, however, is sublime in its indifference to practically anything outside its rule-bound self. Everything is ordered; nothing is possible.

The independent British version is hardly less so, but they have to make their own rules, don’t they, not be ruled by Faceless (probably French-speaking!) Bureaucrats in Brussels.

Most of my working life was spent either in government or in the non-profit realm, which is often a private sector mirror of the government bureaucracy, and what I learned was that effective and enduring bureaucracy was that which was least intrusive and most beneficial to ordinary people and was barely noticed by the overclasses.

In other words, a bureaucracy that runs largely on its own accord in service to the society as a whole as opposed to a faction or class. That may have been the ideal that the EU was hoping to achieve with its bureaucracy, but from the outside looking in, it has a very long way to go.

The US bureaucracy, from my perspective, is a crumbling mess in part because it is so factionalized and serves to perpetuate the antagonisms between factions and to produce harm for those unfavored by whatever faction holds sway.

However, it was never all that much better. There may have been a greater level of agreement to go along with bureaucratic necessities at one time, but that time is long past. Resistance to any sort of outside imposition and rule-following has become widespread standard practice, so we see a resurgence of the arrogance of power by authoritarian Leaders as a response. The bureaucracy is forced to serve the Leader as opposed to Society, prominently so in Florida, but not solely there. The Trump regime was an ultimately failed attempt to perform a similar trick at the national level. Chaos ensued.

Out here in the wilderness, there are bureaucrats and a relatively impressive bureaucracy for such a small population base, but the bureaucracy does not try to control everything in everyone’s life. The notion of public service still endures. A phone call generally reaches someone who can and will provide a needed public service promptly and (usually) cheerfully. Buck passing is rare. Local elected officials are accessible neighbors and sometimes friends from way back. The state has a light touch; the Feds are nearly nonexistent. The pandemic and the response to it threw government and bureaucratic stability to the winds, but self-reliance and mutual aid got us through and much of the upheaval has settled back down into mostly familiar patterns.

Bureaucracy is a necessity in a society like ours, and it’s not going away in any case. But obsessing over rules that make no sense and can’t be broken — and that cause harm — leads to chaos, resistance, violence, and despair.

Jessica

One more piece worth adding: Once bureaucracy and algorithms become powerful, the powerful game them beforehand, eliminating much of the benefit of B&A.