This is the first in a series of articles on Russian grand strategy.

This is the first in a series of articles on Russian grand strategy.

As sure as the sun rises in the East and sets in the West, modern¹ Russian wars begin in a dog’s dinner of disruption and disarray. From the naked aggression of Peter the Great in 1700 against the Swedish Empire² to the present “Special Military Action” that began with significant Russian rollbacks along the entire front, except Crimea, every modern Russian war witnesses their army fall into a fog of confusion and calamity in the first weeks, months and even years against their foe.

Just as certain as rains are to Ireland and ice and snow are to Siberia, however, the Russian army, general staff, politicians and the populace united remain innovative, cunning and intellectually agile: native, instinctual qualities in Russians that are not to be underestimated. Recall, Russia put the first human into space! Just like every other nation, Russian generals come in all stripes. But Russia’s special genius consistently germinates what I call the “learning general.” A learning general makes mistakes, often grievous ones. His hallmark, however, is simple: he never makes the same mistake twice, thereby transmuting fear of failure into audacity in the face of risk and ultimately into victory.

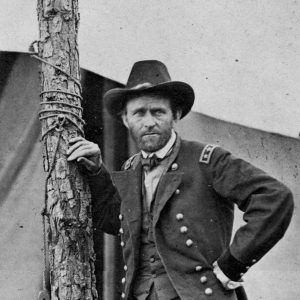

Ulysses S. Grant personifies the modern American example of how devastating a learning general can be. (George Washington was also a learning general.) Patton, Bradley, MacArthur, and Eisenhower were all operationally competent, but not a one of them was a learning general like Sam Grant.

A mediocre student at West Point but something of a standout in the Mexican-American War, Grant was ejected from the army while garrisoning California. All he subsequently touched as a civilian ended in failure, once even reduced to chopping and hauling wood into town that he might, at the very least, feed his family. Of course there is the old lamentable slander that Grant was a drunk, but drunks win wars not.

A mediocre student at West Point but something of a standout in the Mexican-American War, Grant was ejected from the army while garrisoning California. All he subsequently touched as a civilian ended in failure, once even reduced to chopping and hauling wood into town that he might, at the very least, feed his family. Of course there is the old lamentable slander that Grant was a drunk, but drunks win wars not.

After the April 12, 1861 assault on Ft. Sumter, Grant quickly sought a renewed post in the army. He said, “there are but two parties now. Traitors and Patriots.”³ With the help of Rep. Elihu Washburne, Grant was commissioned a colonel in command of 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment on June 14, 1861. By August 5 he was Brigadier General of volunteers. Within months he had captured Paducah, Kentucky, and soon displaced General Fremont. Quickly sizing up his enemy, he beat him handily at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. Ft. Donelson on the Cumberland River was another matter.

First, Grant underestimated enemy strength but quickly recovered, not, however before he failed to close his right flank allowing Nathan Bedford Forest and 700 men to escape. Gathering more forces in defiance of his commanding officer Henry Halleck he soon bulldozed Ft. Donelson into “unconditional and immediate surrender” on February 16, 1862. Grant’s was the first major victory in the American Civil War and he was promoted to Major General by President Lincoln during the week of March 3, 1862.

At Shiloh Grant failed to order his soldiers to entrench in the face of heavy Confederate reinforcements. Unprepared for a bloody Confederate surprise attack, it was only after consulting Sherman that he won the next day with a bold counterstroke that sacrificed thousands. Later in the war came the slaughter at Cold Harbor, followed by an attack on World War One type enfilading fields of fire that destroyed 85% of a Maine regiment in less than twenty minutes at Petersburg. Lastly, the Battle of the Crater.

Grant rose to the highest of commands not in spite of his mistakes, but because he never made the same mistake twice: the defining quality of a learning general. Most men cannot handle a single failure in life. But of life’s most valuable lessons, learning from failure, is the most salutary of all. A general who learns from his mistakes soon grows confident and mature in the face of risk. And with confidence growing the battlefield becomes an enemy boneyard. By the close of the war Grant captured three armies, one at Ft. Donelson, one at Vicksburg and one at Appomattox. He missed a fourth by a whisker at Chattanooga.

***

Three great wars. Three catastrophic beginnings. Three exemplary victories. The Great Northern War of 1700-1721, Napoleon’s Grand Armée of 1812 and the great hubris of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941. Each war birthed in calamity. Each war culminated in total victory. Each won by a learning general.

It is commonplace to view the wars of Russia’s past through the prism of craquelure, but this view is in error. The Great Northern War fought between 1700-1721 is as relevant now as it was in 1812 or 1941.

In 1700 Peter the Great invaded the Swedish Empire with an army reformed along European lines. Gone were the steppe warriors, the streltsy, a rag tag feudal lot armed with a pike and an arquebus. Their hereditary forebears, mounted archers, defeated the Mongols at their own game. (Even then the Russians were a learning lot.) Peter’s new model army exchanged Parthian shot† for musket barrage and charge of cold steel.

The war began well for the Swedes, poorly for the Russians. The first battle at Narva, November 30, 1700 was a disaster in every way, except one. Peter’s command structure was a tapestry of confusion. Seeking reinforcements Peter was not even on the field of battle when Charles XII, king of Sweden arrived. Moreover, Peter’s army was too green: entire regiments fell, raked by musket and cannon balls, retreating ignominiously within earshot of the enemy howls of a bayonet charge. Only the Preobrezhinksy and Semyenovsky Regiments held fast, formed squares and fought on while the other twenty-nine regiments of Peter’s army surrendered to Charles XII.

The war began well for the Swedes, poorly for the Russians. The first battle at Narva, November 30, 1700 was a disaster in every way, except one. Peter’s command structure was a tapestry of confusion. Seeking reinforcements Peter was not even on the field of battle when Charles XII, king of Sweden arrived. Moreover, Peter’s army was too green: entire regiments fell, raked by musket and cannon balls, retreating ignominiously within earshot of the enemy howls of a bayonet charge. Only the Preobrezhinksy and Semyenovsky Regiments held fast, formed squares and fought on while the other twenty-nine regiments of Peter’s army surrendered to Charles XII.

Preternaturally gifted towards warfare Charles XII destroyed Peter’s allies, ad seriatim, forcing a separate peace on both Denmark-Norway and the Saxon-Polish-Lithuanians by 1707. Meanwhile, Peter learned many a hard lesson, but three will suffice: he simplified his command structure, he blooded his armies, and finally, beguiled would-be invaders in and then scorched the earth. Charles XII, emboldened by his victories over Peter’s allies invaded Russia in 1708. Peter retreated into the vastness of mother Russia until the winter of 1708/09 arrived. For the first, but not last time, the cold arctic air manifested two of Russia’s most unforgiving generals: January and February. By spring’s arrival Charles XII’s supply lines were dangerously over-extended, his army near exhaustion. Nine years after his Swedish land grab, Peter led his army to victory over Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava on July 8 1709. Although the war between the Sweden and Russia was not officially over, Poltava was decisive and had so disrupted the balance of power in central Europe that his original allies (self-aggrandizers who had signed a separate peace with Sweden) rejoined the fight so as to grab their piece of the once formidable Swedish Empire.‡

One-hundred and three years later, on June 24, 1812 Napoleon crossed the Niemen River into Russia with 450,000 men under arms. The flat-footed Russian High Command had no answer to this brazen act of aggression. After weeks of forced marches Napoleon won at Vitebsk and then smashed whatever confidence Russian General Barclay de Tolly had left when he captured the fortress city of Smolensk. Russian General Bagration (actually a Georgian) was faulted for not relieving Barclay de Tolly and both were sacked in favor of veteran of the Ottoman wars, Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov. Kutzov, loathed by the Czar Alexander I, learned the art of war after multiple blunders in three Russo-Turkish wars which preoccupied Russia prior to Napoleon’s invasion. Napoleon’s troubles soon began in earnest as Kutuzov employed scorched earth tactics and near-guerilla style attritional warfare against Napoleon and his Marshals. Weeks more of forced marches befell Napoleon’s Grand Armée, until Kutuzov wheeled around on September 7, 1812 at Borodino and fought Napoleon. It was a bloody Pyrrhic victory for the French. The Russian army survived intact to fight another day. Seven days later Napoleon and his now depleted army of 100,000 captured an arson-scorched Moscow. Napoleon howled imprecations at the Czar as Moscow burned, “the barbarians, the savages, to burn their city like this! What could their enemies do that was worse than this? They will earn the curses of posterity.”¤ His logistics shattered, Napoleon had no choice but to retreat, losing all but 35,000 of his once 450,000 strong army. Napoleon’s aura on invincibility destroyed, Kutuzov’s army had turned the tide.

One-hundred and three years later, on June 24, 1812 Napoleon crossed the Niemen River into Russia with 450,000 men under arms. The flat-footed Russian High Command had no answer to this brazen act of aggression. After weeks of forced marches Napoleon won at Vitebsk and then smashed whatever confidence Russian General Barclay de Tolly had left when he captured the fortress city of Smolensk. Russian General Bagration (actually a Georgian) was faulted for not relieving Barclay de Tolly and both were sacked in favor of veteran of the Ottoman wars, Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov. Kutzov, loathed by the Czar Alexander I, learned the art of war after multiple blunders in three Russo-Turkish wars which preoccupied Russia prior to Napoleon’s invasion. Napoleon’s troubles soon began in earnest as Kutuzov employed scorched earth tactics and near-guerilla style attritional warfare against Napoleon and his Marshals. Weeks more of forced marches befell Napoleon’s Grand Armée, until Kutuzov wheeled around on September 7, 1812 at Borodino and fought Napoleon. It was a bloody Pyrrhic victory for the French. The Russian army survived intact to fight another day. Seven days later Napoleon and his now depleted army of 100,000 captured an arson-scorched Moscow. Napoleon howled imprecations at the Czar as Moscow burned, “the barbarians, the savages, to burn their city like this! What could their enemies do that was worse than this? They will earn the curses of posterity.”¤ His logistics shattered, Napoleon had no choice but to retreat, losing all but 35,000 of his once 450,000 strong army. Napoleon’s aura on invincibility destroyed, Kutuzov’s army had turned the tide.

Fast forward, in the argot of internet America, one-hundred twenty-eight years, three-hundred and sixty-three days to June 22, 1941. Three million, eight hundred thousand men, three-thousand seven-hundred ninety-five tanks, twenty-three thousand pieces of artillery, over thirty-thousand mortars, five-thousand six-hundred and seventy-nine aircraft and over one-million two-hundred thousand horses and vehicles under the aegis of Operation Barbarossa invade the Soviet Union. Their objective was the A-A line, a straight line running from Archangelsk to Astrakhan. Lebensraum. By late August Kiev had fallen, soon too had Minsk and the Baltic states. Leningrad was besieged. All of the crucial Donbass region gone and so too the Sea of Azov. Army Chief of Staff, Zhukov was sacked and sent to the rear to command reserves. The Wehrmacht’s Operation Typhoon came within 87 miles of Moscow in late September when Stalin threw 800,000 (83 divisions) men at the Germans. Only 25 of the divisions were at effective strength, but they were just enough to hold the Germans to within 15 miles of the capital. Multiple crack Siberian divisions, who had beaten the Japanese at Khalkin Gol, counterattacked and drove the Germans back a hundred miles. With supply lines and entire army groups in disarray Hitler order retrenchment and reorganization. The drive to Moscow ground to a halt.

In desperation, Stalin recalls his most effective general to plan a new counter-offensive. Striding onto center stage comes the titan: one Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov. His early failures during Operation Barbarossa hardened him and prepared him to deal with the capricious autocrat Stalin. He quickly conceived Operation Uranus (Stalingrad) and Mars (Rzhev Salient) and put them into motion simultaneously. His double envelopment of Paulus’ Sixth Army at Stalingrad conjured the ghost of Hannibal at Cannae, 2,140 years before. But the Battle of the Rzhev Salient was an operational defeat. Lesson learned: no multiple operations simultaneously. A learning general, Zhukov then went on to best the tactics and strategy of Hannibal at Cannae a second time laying a well-prepared trap the along the Kursk Salient.

In desperation, Stalin recalls his most effective general to plan a new counter-offensive. Striding onto center stage comes the titan: one Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov. His early failures during Operation Barbarossa hardened him and prepared him to deal with the capricious autocrat Stalin. He quickly conceived Operation Uranus (Stalingrad) and Mars (Rzhev Salient) and put them into motion simultaneously. His double envelopment of Paulus’ Sixth Army at Stalingrad conjured the ghost of Hannibal at Cannae, 2,140 years before. But the Battle of the Rzhev Salient was an operational defeat. Lesson learned: no multiple operations simultaneously. A learning general, Zhukov then went on to best the tactics and strategy of Hannibal at Cannae a second time laying a well-prepared trap the along the Kursk Salient.

Some scholars claim the idea of a trap at Kursk was General Rokossovsky’s (error corrected ~spk) idea. But I believe that to be untrue. The idea, aforementioned, was developed by Zhukov who brooded over the failure of the Rzhev Salient during Operation Mars. He learned from that mistake and employed the lesson at Kursk. Here, finally, was the epic battle of World War Two; the Poltava, the Borodino, Maloyaroslavets, Vyazma and Berizina campaign. Here, the Soviets ripped the guts out of the Wehrmacht and decided the fate of the Nazis. It remains the single largest battle in the history of human warfare. The entire Soviet populace within a hundred miles participated weeks before in laying the trap for the Nazis. Mothers and sons dug tank traps, ditches, machine gun and mortar nests, wrangled murder holes out of raw concrete just laid. This they did for their husbands, fathers, elder sisters and brothers all of whom were manning tanks, mortars, rifles, machine guns, artillery and planes. At Kursk the Russians gave no quarter to the Nazis and zero magnanimity in their defeat. It was total war and mass slaughter on a scale not even I want to contemplate.

***

Charles XII can be forgiven for invading Russia. No precedent existed for Russia’s behavior, especially in a Westphalian world order. But for Napoleon the precedent was all too clear. Hubris makes fools of great and evil men alike. Napoleon is the rule, not the exception. The same can be said of Hitler. His actions uncorked the rule, just as Odysseus’ shipmates uncorked and subsequently reaped the whirlwind.

Aside from Russia’s propensity to propel learning generals to the fore, there is another theme running, unsaid, through these three wars. Three wars saw their vital interests, existential in nature, threatened. How did Russia win such violent, destructive wars that laid waste to thousands of miles and killed millions of people? The question of Russian grand strategy and why they are fighting in the Ukraine will be addressed in my next post. Until then, a Russian proverb, a hint: “All Roads lead to Rome, but the road to Moscow is a matter of choice.”

Choice indeed.

———–Footnotes———-

1: Modern Russia begins when Peter the Great inserted his nation into the Westphalian System upon entering the Great Northern War of 1700-1721.

2: At the time, the Baltic was a Swedish lake. Virtually all the lands surrounding the Baltic were sovereign Swedish land. And Peter the Great was hungry for a Baltic port, which he founded in 1703: Saint Petersburg.

3: Brands, 2012, p. 123.

†: A “Parthian Shot” is a horse archer in feigned retreat turning his body backwards firing a recurved bow at full gallop at an enemy in pursuit. “Parting shot” is a modern English idiomatic derivative of “Pathian Shot.”

‡: Sweden fought for another twelve years. Russia did not sign a separate peace, like his allies had before him. Peter honored his treaty obligations with his partners to the letter.

¤: Mikabridze, 2014, p. 92.

Kelley lives in San Antonio, Texas. He has a Bachelor’s degree in European History, and two Master’s: International Relations and Political Economy and another in History, focusing on the medieval trade routes of Inner Asia.

Jan Wiklund

The last question can be answered in the same way as “how could the Vietnamese win against the US?”:

Their own country meant more to them than to the invader. Or as Clausewitz said: defence is always stronger than attack.

Soredemos

This doesn’t matter, it’s war nerd bullshit, but the ‘crack Siberian divisions’ thing is a common myth. It’s simply not true. https://www.operationbarbarossa.net/the-siberian-divisions-and-the-battle-for-moscow-in-1941-42/

The new divisions were freshly raised west of the Urals.

Sean Paul Kelley

Soredemos,

Incorrect. See Gilbert, 1989, p. 245: In little over a month, the Soviets organised eleven new armies that included 30 divisions of Siberian troops. These had been freed from the Soviet Far East after Soviet intelligence assured Stalin that there was no longer a threat from the Japanese.

I would also encourage you to read Otto Preston Chaney’s biogrpahy of Zhukov. I’ll omit the Russian language treatments of Zhukov, as they are not in translation.

Willy

Amazing the variety of Russian Ways. In one age, inexorably grinding down the greatest army ever. In another, a comedy of meatgrinding errors. Never underestimate the power of “morale” I guess, at every level.

Still, it’s interesting how being stuck in a grayly frozen landlocked expanse influences thought and culture. Not that taking advantage of such a land during war is a stroke of genius. Don’t all the wisest armies do like the Viet Cong, Mujahedeen, or American colonial patriot did, take advantage of what you got? I’d think the genius would be in knowing how to disable enemy advantage in advance. For a lesser cost of course.

Mary Bennet

Mr. Kelley, in WWII, how important do you think was Soviet intelligence gathering, keeping in mind that Stalin didn’t always believe what the moles were telling him?

Soredemos

@Sean Paul Kelley

I mean Gilbert can say that in summary, but the stuff I’ve read that go into detail of specific divisions, armies, and timetables seems to tell a different story.

Dan Kelly

Why does “Sean Paul Kelley” have that little red icon that is usually next to Ian’s name? I clicked on the “Sean Paul Kelley” name and it immediately links to “Best betting Sites in Tanzania”

https://seanpaulkelley.com/

Interesting.

elkern

(typo: General “Rossokovsky” should be “Rokossovsky”?)

Looking forward to Part II, to see how Kelley applies this perspective of Russian Grand Strategy and “Learning Generals” to the war in Ukraine.

I’m a little skeptical; I’m no expert on Russian Military History, but I know enough about it to wonder at some things Kelley has [so far] left out. One is a longstanding emphasis on Artillery, which seems particularly relevant to tactics in Ukraine. Another would be why Russia seems to have never produced a “Learning Admiral”; (google “Russian Second Pacific Squadron” if you have an hour to spare and want a deeper appreciation of the line “No more Navy jokes” in The Death of Stalin). This is also currently relevant, as Ukraine – with *way* more than a little help from Britain – has sunk most of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Of course, the other big question is how effective Generals January and February – who have destroyed vast foreign armies on Russian soil – will be on Offense. Presumably, they are scheduled to break the will of the Ukrainian people, facing Winter with a broken electrical grid?

GM

The big difference is that neither Napoleon nor Hitler had long-range missiles and nukes, i.e. the means to destroy the Russian rear.

NATO now does.

And Putin is now allowing them to fire those at will.

This is the recipe for how Russia gets defeat, unlessn ukes start flying towards Europe now to pre-empt it.

Ian Welsh

Sean-Paul Kelley used to run the “Agonist” a fairly large blog site. Before I was managing editor at FDL, I was managing editor at the Agonist, from 2005 to late 2007. Sean-Paul has author privileges here, and has since the blog started, though he’s rarely used them.

One of the smarter people I know.

Mark Level

It’s a great piece. I will confess as much as I love history, military history per se has never been a particular focus of mine (I rather dislike the Great Man Theory of History, for obvious reasons), I feel like I learned quite a bit reading this.

There is an unusual serendipity in the mention of Kursk late in the essay. Earlier today, I saw videos following up on the insane latest Ukrainian Hail Mary pass (or more likely PR move to pretend “We can win”) of attacking east into the Russian city of Kursk, to (a) make Russia’s leadership look bad by murdering civilians, & (b) more substantively, to possibly try to grab the Kursk Nuclear Plant & use it for meltdown blackmail.

Of course, this was bound to fail (& shockingly, they are sacrificing their Elite, Azov (Neo-N@zi) forces, so important is this diversion evidently. Anyway, both the Duran and also Ray McGovern (on Judge Napolitano) seem to think that this Pyrrhic effort means the Zelensky regime will be defeated before the US elections, the collapse is imminent.

If history rhymes rather than repeating, it is still shocking how some refuse to learn anything from it. To sacrifice large sections of Ukraine & doom the country demographically for a NATO wet dream will be remembered as “March of Folly” level destructive, homicidal (& suicidal) stupidity.

j

One of the most underestimated concepts of all matters Russian is бардак. Things are always a mess to some degree in Russia, with the peope always abandoned by leadership to some degree, and people are used to managing their affairs, and thriving, nevertheless.

What this translates to in military matters is that it is no surprise most things start off unprepared and on the wrong foot, but they get sorted out. You never know too well beforehand what’s solid and what’s not anyway, so there shouldn’t be too much sweat about it anyway. But someone of competence will take charge, give an exhaustive short assessment of the situation and of whoever is in charge via about five minutes of swearing bloody murder, something the Russian language is uniquely suited for, and people will follow.

That this is the way is also mirrored in Russian military doctrine. Unlike Nato doctrine, which seeks to reinforce and plug the units and sections of the front that are in trouble, Russian doctrine seeks to help whoever is successful at the moment, and leave the unsuccessfuls to manage on their own. This works. The Nato approach generates a lot of reactionary maneuver and logistics without much to show for it, Russian approach generates initiative, breakthrough, and opportunity. Even Nato’s own officer training emphasizes that when you are reacting to the enemy, you are losing, you need to break the loop and make the enemy react to you, yet on the doctrine level, this understanding has not taken root.

Add to this the fact that the US current way of war is built upon total information availability and working communications, while Russians expect to not have any and still do their job. And on top of that, who has paid attention, that already back in the Russian entry into the Syrian civil war, and now in Ukraine, the Russians have demonstrated next level EW and signal jamming Nato still has no answer for… While being no fan of Russia, if I should care for an honest assessment of the chess board, I cannot but come to the conclusion that Russians know who they are and what the strength and weaknesses of their own and their enemies are, and have put this knowledge to a better use than their enemies. Case in point, the quiet desperation of Nato impotence in Ukraine.

mago

Long game, short game.

Russia has a long running history and vast experience in a vast land.

The divided US has Biden, Blinken, Harris and Trump, a short field and weak teams. Maximum hubris, failing strategies.

Pithy analysis from SPK, brilliant in its scope.

Agree or disagree, we all have a view, and every horse has an ass, although as Ken Kesey observed in “Sometimes a Great Notion”, there are more asses than horses.

Never mind.

Soredemos

@elkern

“Ukraine – with *way* more than a little help from Britain – has sunk most of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.”

No, it hasn’t.

Such a fascinating war from a propaganda perspective. Because the things Ukrainian supports think are so wildly disconnected from the reality, and much if Western intelligentsia and leadership seems to genuinely believe it as well.

‘Well you ust blindly believe Russian propaganda’ will be the retort, but the image of the war that can be clearly gleaned from even just Western media fundamentally supports the Russian view. We’re at the point where the commander of the Ukrainian military is admitting Russia has more equipment than it started with (and of course he needs more money and gear to win the fight, which he can still totally win, honest).

Carborundum

Good to see you SPK, glad to see that you are still about. I guess my question would be how this historical tradition influences modern Russian strategic thought. More recent campaigns have been pretty mixed, to put it charitably. Afghanistan, operationally, was a total goat rope and had a strategic concept every bit as intellectually bankrupt as the West’s more recent engagement. Chechnya I don’t know as much about, but doesn’t make me optimistic there’s a great concept other than bulk forces waging ultra-attrition waiting to be tapped. Looks like they were thinking Hungary, found out this isn’t that and have been basically pouring increased resources ever since.

Seems to me that they have a significant upper hand in that they likely have escalation dominance and, while they are devoting an astounding amount of resources to something that should be kept to an economic rounding error given all the other challenges they have, they do, in fact, have those resources and are willing to expend them on military nonsense. To prevail, Ukraine has to stalemate them with escalated costs while being very economical in their own expenditure of forces. In theory, this should be possible but little I have seen over the past two years leads me to believe they have the chops and balls – operationally or strategically – to pull that off.

I rather suspect that the most analytically significant aspect of all of this is actually the second order effects on the indirectly engaged players.

bruce wilder

The essential tasks of specifically “grand strategy” are figuring out how to win the war and in winning the war, win the peace. The faults of some of history’s most celebrated generals have included thinking that winning some battle in spectacular fashion would somehow automatically win the war and thinking that winning the war was enough to dictate the peace on any terms.

Charles XII and Napoleon were very good at winning battles. Robert E Lee was another who appears to have thought a well-won battle could be “decisive” with no further management of context or consequences to make it so.

What madness led Charles XII to wander so far afield from the Baltic as Poltava in Ukraine? What kept Charles XII in the war at all after the defeat of Augustus the Strong? Peter had what he most wanted for Russia: an outlet on the Baltic. Peter had been back to Narva and that was over. Peter was fighting to win a peace with certain desired features. Russia stayed in the war because Sweden did. The destruction of the Swedish military machine became the grand strategic objective as a result.

What madness led Napoleon to assemble the massive Grand Army, a force far beyond the logistical capacities of the day? Napoleon did not know how to make a lasting peace. He could not stop himself.

What madness leads Germany to anything but an alliance with Russia for the resources the Russians have and Germany needs to prosper? In the Second World War, the Germans made clear early on that they intended to exterminate their Slavic opponents. No other German war aim could have provoked a more desperate, maximum effort or made Stalin a more appropriate leader for the existential struggle that followed. The contrast with the First World War, where German willingness to conclude even a humiliating peace was sufficient to destabilize the Russian polity, is instructive.

Willy

In the Second World War, the Germans made clear early on that they intended to exterminate their Slavic opponents. No other German war aim could have provoked a more desperate, maximum effort or made Stalin a more appropriate leader for the existential struggle that followed.

With the evidence supported by Youtube videos? The USSR had weathered the worldwide depression fairly well and built much for their working comrades (outside of Ukraine of course), and then Hitler attacked after having signed a peace treaty. Those were facts your average working comrade could put their hands on, with no reading between the Pravda agitprop lines required.

Today, public support against Russia is high in Germany. There’s no way to accurately gauge the same for Russia, since one can be imprisoned for giving the wrong answer.

Sean Paul Kelley

I’ll try to address many, if not most of your comments in subsequent posts. I only wish to address three issues at present.

First, the site seanpaulkelley.com: I stopped paying for the URL about ten years ago and have zero control over its content. A fool’s move in hindsight, but by 2014 I had become so disillusioned with blogging and internet life, as opposed to real life, that I walked away.

Second, this is the first blog post I have written in ten years. I began The Agonist in 2001 and blogged there until 2012. I maintained seanpaulkelley.com as a personal travel blog (I’ve visited 65 different sovereignties) until 2014.

Lastly, I had forgotten just how smart you folks are. All of your questions have been intellectually stimulating–whether I agree or disagree–and I thank you for that. The intellectual back and forth is something I have sorely missed since leaving graduate school in 2017. Again, thank you. Color me impressed.

Dan Kelly

Thanks Ian. Looking forward to more from Sean-Paul Kelley…however rare that may be.

a well-won battle could be “decisive” with no further management of context or consequences to make it so

Sounds like military ‘neoliberalism.’

More often than not, progress is knowing when to stop. It seems it’s the same with ‘winning’ the war.

——————————————————————-

I don’t want to divert attention from a military strategy thread, but I’ve been listening to the late Jerry Garcia’s 1974 album ‘Compliments’ and it includes a neat version of ‘Russian Lullaby’

https://invidious.jing.rocks/watch?v=kc5NKNpN_-I

Sean Paul Kelley

One last note, in regards to Rokossovsky vs. Rossokovsky. I’ll leave it to you Russian speakers to get my joke, as one commenter noted, Russian is uniquely suited (Mat is the term on would use) to cursing.

Иногда я бываю тупоголовым дураком.

Or perhaps Lermontov said it best: Знакомство юнкерского хуя!

elkern

Soredemos – OK, yeah, I should have said “Ukraine… has sunk *or severely damaged much* of the Russian Black Sea Fleet”.

In general, I’m quite skeptical of Western MSM reporting on the war in Ukraine; MoA and Naked Capitalism are my main alt sources. I guess I had kinda bought into Ukrainian/British reporting on the naval side of the war, as my alt sources generally didn’t [bother to] refute that propaganda.

British sources seem particularly gleeful when bragging about Ukraine hitting Russian ships with Storm Shadows. Crowing about that seems really stupid for country (Britain) with a small and shrinking military that its collapsing economy can no longer afford. *Sigh*, fallen Empires are prone to dangerous revivalist dreams of Imperian Grandeur….

But still, sinking the Moskva *was* a serious blow, and even if the other reports are exaggerated, I’d still bet that Russian naval losses have been pretty bad.

elkern

SPK –

plz explain the joke, for those of us who don’t speak/read Russian? Sadly, not being familiar with your old Blog – and your expertise in Russian? – your alt spelling looked like a rookie mistake to me. Turns out I’m the rookie…

Def looking forward to your next Post.

StewartM

Having read Glantz, and others, I’ve never read that Zhukov was relieved by Stalin before the Battle of Moscow. He did lose his position as head of the General Staff, but that’s because (he said) he favored the abandonment of Kiev. But even then, he still was overseeing important jobs (the Yelyna counterattack, the Lenningrad defense, and the Moscow defense). There’s a story that Stalin wanted to have Konev shot after the the Vyazma and Bryansk disasters of October 1941, and Zhukov shot back “You did that with Pavlov in June 1941, and it did not improve the situation at the front. Konev is a good officer who was simply given an impossible assignment” or something like that.

And your comment that:

Lesson learned: no multiple operations simultaneously

is utter nonsense. In fact, the STRENGTH of the Soviet army vs the Germans Kursk and beyond is that the Soviets focused on multiple thrusts, not single or dual thrusts, like the German practice. Having multiple operations (often carefully timed) maximized the Soviet advantage—the Germans could and often did stop any given Soviet thrust, but any defensive victory they achieved was moot, as the Germans couldn’t be everywhere on the front in force, and where they weren’t there were major Soviet offensives pushing through. The Germans were thus like the proverbial Dutch boy and the dike story, save that there’s too many holes for his fingers.

(This was equally true of the West in France in 1944, which was the strength of Eisenhower’s ‘broad front’ strategy, the Western allies had universally strong units everywhere, while the Germans could only be strong in isolated spots).

In that light the failure of the Rzhev offensive (“Zhukov’s greatest defeat”) must be seen in the light of the success of Operation Uranus, Little Saturn, and Neptune elsewhere on the front. But Kursk itself is an example of it, too. I wouldn’t call Kursk a ‘smashing victory’ (more like the Soviets fought the Germans to a standstill, inflicting heavy casualties on their tank forces and infantry), but the fact is that the Germans had concentrated some 3,000 of their roughly 3,500 AFV in the East at the Kursk salient, against 5000 Soviet AFV (out of nearly 10,000). This left only 500 German AFV to face off against 4,000 + Soviet AFV everywhere else across the Eastern Front. And that’s what the Soviets did once the German drive on Kursk was intercepted–counterattack at the other weaker spots, first Orel, then Izyium, then the Mius river line, and finally the Smolensk direction. This was the theme for all the fall of 1943; Germans occasionally winning defensive victories against Soviet penetrations but having those victories meaningless because everywhere else there were major Soviet forces pouring through other gaps. Often German panzer forces were instrumental at staving off complete disasters, until finally in June 1944, starting with Bagration, the bottom just fell out.

This is actually also echoing Grant, as that’s essentially similar to Grant’s 1864 strategic campaign against the Confederacy–offensives everywhere, and the Confederacy might be able to contain some of them but it couldn’t in the long run contain all of them. Though I differ somewhat with you about Grant being a ‘learner’—I don’t see that as his strongest character trait. Rather, it was his realization (learned very early in the war) that his enemy wasn’t some superman and that he was probably also just as in much difficulty if not more than he was. And it was Grant’s ‘confidence in success’ that Sherman noted.*

(Early in the war, Grant was in charge of a body of troops (regiment? brigade?) and ordered to charge an entrenched Confederate position on top of a hill. Grant said his heart was in his throat all during the charge, that he was scared, only to find out his opponents had vanished already and the position was abandoned. “It occurred to me”, Grant wrote, “that my opponent was just as afraid of me as I was of him. This was not something I had considered before, but it was something I never forgot”.)

*- I once worked with someone at a community service sponsored by my old company. My relationship with this person, who headed the effort, I joked that he was US Grant I was Sherman. I’d be fretting and pacing about all the things that might go wrong, and how to address them, like Sherman would have, while he was just say “Yeah, we’ll work it out. Whatever happens, we’ll find a way to deal with it.” That’s US Grant.

I’d not fault Grant for not entrenching at Shiloh, as almost nobody entrenched in 1862. And even later, entrenching doesn’t prevent tactical surprise and defeat (ask Early’s division after the Battle of Rappahannock Station in 1863). I would say that Shiloh just showed Grant’s confidence that no matter what went wrong, “we’ll figure out a way to win”.

Sean Paul Kelley

@elkern

Иногда я бываю тупоголовым дураком means: Sometimes I’m a thick headed fool. It’s used as a self-deprecating curse. One never says that to someone else’s face. Big no-no.

The quote from Lermontov is a bit more explicit, and derives from what the Russians call Materi Yazik (ма́терный язы́к) — it’s an very extensive near dialect of absolutely brilliant foul lanaguage, curses and the like. Google it or check out an Amazon book on the subject. I guarantee you will laugh for days. Russian is an extraordinarily rich language and materi yazik is but one proof.

Lermontov’s quote means someone who’s prone to making rookie mistakes: Знакомство юнкерского хуя! but the direct translation is: introducing the cadet’s dick!

My absolutely favorite Materi Yazik phrase is used when a guy friend asks you what you are doing. In English we’d reply, “not much” or “just hanging around.” In Russian one might say, “хуем груши околачивать,” which literlally translates as “just banging my dick against a pear tree.”

In case you are wondering: I was married to a Russian for almost ten years and have a half Russian son who has spent way, way too much time with his cousins in Russia. His Russian is native. Mine is secondary.

bruce wilder

Willy: With the evidence supported by Youtube videos?

The German authorities chose as a matter of deliberate policy to breach the Geneva Conventions with regard to Soviet soldiers captured in initial operations in 1941, killing over two-thirds by early 1942 by exposure, disease, starvation, overwork in slave labor camps and summary execution of the wounded or resistant. The Germans achieved one of the highest death rates from mass atrocity in military history in 1941.

Willy: There’s no way to accurately gauge the same for Russia, since one can be imprisoned for giving the wrong answer.

I don’t know that things are that much different in Germany, practically or even legally. Banning one of the largest political parties is being entertained seriously. I am dubious about any assertion that Germans are enthusiastic about risking nuclear war, or radically reducing the standard of living by de-industrialization. The popularity of having major German infrastructure destroyed by its so-called, “ally”, cannot be gauged because Germany is still pretending it did not happen.

Sean Paul Kelley

Stewart M: I confess, you’re argument is compelling. Citing Glantz is a reminder too. I suspect the error is mine. What I should have said was that after Stalingrad and the failure of Rzhev, Zhukov’s became more willing to delegate operationally to a cadre of generals he trusted, thereby narrowing his focus.

As for your interpretation of the aftermath of Kursk being, how should I put it, “Grant-like” that’s quite elegant. Thank you. I had not thought of it that way. Nice to know someone comprehends Barbarossa and Grant. That’s a tall order for anyone, one I still struggle with at times.

As a side note: I wanted to discuss Suvorov (18th century) and Brusilev (WWI) but the post would have been overlong and fucking unweidly. Sadly, dust bin of history for those two geniuses.

marku52

My Grant story: before the campaign into N Virginia, Grant is working with a quartermaster–how many wagons of wheat, how many wagons of powder, etc.

Grant answers easily.

“How can you know this?” Asks the quartermaster.

Ans: “I don’t. If I am wrong, we will adjust. But I must decide, or else nothing can go forward.”

He seems to have been very comfortable with uncertainty.

Willy

bruce, you miss my point. You seem to be assuming that all Russians back then had as much access to credible instant information as Americans do today.

No wait a sec. You’re the guy who’s constantly harping on how messed up our access to credible information is today. And now modern Germany too.

So let me rephrase that. Since nothing can be known for certain, not in the USA, Russia or Germany, both then and now, we’ve gotta go with what facts seem reasonably certain.

Fact #1 for me, is that this thing is taking a helluva lot longer than anybody expected. There have to be reasonable reasons for that, outside the bounds of ‘the media ruins everything’. I also seem to be having a helluva time falling for the constantly shifting revisionist history we see around here.

Purple Library Guy

I don’t know a ton about military history. But, I have been watching this war pretty closely through most of it. And I think there has been a general misinterpretation of the big Russian retreats. I’m not sure about the first one where they were all around Kiev and some other places and then left–I’ve seen claims that was done for political reasons, but I dunno, and I’ve seen claims that they left that area because they had a front solidified in the Donbass and wanted to basically just have one front, so they took their forces away to the Donbass to unify them, but I dunno–seems like a weird reason to give up on the opponent’s capital. But whatever they were doing there, I didn’t see any evidence that there was some big Ukrainian offensive that they were retreating from.

The other two major Russian retreats were definitely done despite not really wanting to, because they were having trouble with the Ukrainians, but again, they were not as such because of Ukrainian forces pushing them back. The southern one was in response to the Ukrainians successfully whacking the bridge across the Dnipro river. They realized their logistics were screwed, so they retreated across the river. That also gave them a big piece of very easily defended front, at a time when the army committed to the war was actually smaller than the Ukrainian army, before they had built up and brought in a bunch of new forces. But they lost hardly anyone in the retreat. Indeed, it almost felt like the Ukrainians were just letting them do it, not really pushing hard on their heels–I remember at the time thinking “Won’t it be kind of tough to get everyone back across what’s left of the bridge while under attack? Won’t the Ukrainians totally bleed them in that process?” But for some reason, they didn’t.

Finally there was the big retreat up north, which suddenly gave up a ton of turf. This seems again to have been largely based on the Russian army at the time being basically too small for the job they by this time realized they were involved in. At the time, the Russians were generally advancing slowly over a lot of the front, including up there. But it seems like they decided they were getting overextended and had pushed into areas that basically weren’t very defensible. So they did a big retreat . . . but it was, again, not really in response to a Ukrainian offensive. It was planned. They retreated to prepared fallback positions and stopped there, along a shorter more defensible line. They lost some people in the retreat, but the Ukrainians lost far, far more in the process of chasing them.

In general, I think for the Russians this war has been more about attrition than territory–not purely, they’re happy to grab territory, and the process of trying to take territory is a major way for them to make Ukrainian forces expose themselves so they can cause that attrition. But the Russians have generally been much more willing to retreat to either save troops or cause casualties than the Ukrainians. Those big retreats were examples of that mind set.

The biggest Russian mistakes in the war were IMO not those retreats, but things like their repeated attacks on Bakhmut that lost a ton of troops and vehicles (and got a general sacked, which the retreats did not). The biggest Ukrainian mistake was probably that big counteroffensive, which just tore the guts out of their army–but that’s really NATO’s mistake, for kind of politically requiring them to do it if they wanted to keep getting support.

I do think the Russians initially thought this would be over a lot faster. But what it comes down to is, Ukraine has had a lot more attrition in them than expected, and kept on keeping on despite hideous losses. They lose masses of soldiers, they recruit more. They lose tons of materiel, NATO gives them some more. Plus, I don’t think Russia anticipated the strong impact drones had on this war. Russia has more drones than Ukraine does, and some of them are better than Ukraine has, but it’s not a huge mismatch like with artillery, planes or missiles. And drones seem to be a bigger help to the defender. An effective attack in that kind of war sort of needs to be led by armoured vehicles, and drones are really good at whacking those armoured vehicles. This has definitely been a pain in the ass for the Russians; they’ve tried to deal with it using electronic warfare, using those “turtle tank” things and other adaptations to make vehicles more survivable, and lately sometimes by attacking with swarms of motorcycles and no armoured vehicles at all. All these tactics have had some successes but not really solved the problem. And the Ukrainians have fought hard–stubbornly, valiantly, sometimes skilfully.

But despite all that, and despite the recent counterattack which, really, I gotta hand it to the Ukrainians for a gutsy move that the Russians are scrambling to handle–the attrition is taking its toll. Over most of the war, the Russians have maintained a lopsided advantage in terms of people killed and stuff destroyed, and it’s been getting worse over time as the Russians destroy Ukrainian artillery and degrade Ukrainian air defences, at this point letting them bomb the front at will. The Russian advance keeps getting a little faster and a little faster. In my opinion the recent Russian opening of that new front up north was not really about taking territory there, it was mostly about stretching the front line a bit further, expecting that areas of too little coverage would start appearing that the Russians can take advantage of . . . and this has in fact been happening. In one sense, that Ukrainian counterattack may be doing the Russians’ job for them by stretching the front further and adding another source of attrition. Recently there is also apparently some violent resistance to Ukrainian recruitment, involving fairly large scale burning of recruiters’ vehicles, particularly in the Odessa region. The civilian population of Ukraine may be reaching the end of their tether.

So I think we’re getting fairly close to the end, relatively speaking. Which is lucky for Russia, since although up to now I would have said their economy is doing fine despite the war and the sanctions, I understand there are now beginnings of trouble; they’re starting to see some inflation, apparently.

j

Regarding uncertainity, in my NCO training back in the days there was a point made about the importance of making a decision – making a decision allows you to get moving torwards your goal. If the decision was wrong, you have gained knowledge and experience, and you change what’s needed and go on. If no decision was made, you are at best still where you were before, but have probably taken some lead in the mean time with nothing to show for it.

Or, to put it in the words of philosophers, Nietzsche: “make a decision, and answer to it”, Sartre “indecision is a decision too, and usually the worst one”.

Regarding multiple simultaneous offences, in the words of Ron Swanson: “Never half-ass two things, whole-ass one thing.” One should not divide their attention, but that does not mean someone else should not take on some other project at the same time. Zhukov tried to manage two operations simultaneously, and that was a mistake. Next time, he had others do the other ones.

But there is also a limit to the great general side of war analysis. Any of those generals will also tell you war is primarily a competition of logistics. The war between SU and Germany was going to break out sooner or later, but Stalin had thought he had a few more years to prepare, and Hitler got him by surprise. What followed was a scramble in the SU to evacuate their factories to behind the Urals and get them going again. The human cost of the Battle of Stalingrad is directly related to the lack of material support on the Soviet side. The battle turned when tanks started arriving in numbers. Not much later the production machine was in full swing and the war itself turned. And let’s not forget the logistics problems Germany was facing either, and neither what was by then the Hitler problem.

It’s not too difficult to make successful offences in multiple locations when you have ten times the advantage in those places, you would need a general of Švejkian quality to fail that. The Germans still put up quite the fight, but in the grand scheme of things, there was nothing to do anymore.

shagggz

@PLG,

Russia did indeed expect the war to end much quicker, as their goal was to force Ukraine to the negotiating table. Their retreat from Kiev was a goodwill gesture for the seemingly-concluded peace talks, until Boris Johnson insisted that “let’s you and him fight.” It was this extent of Ukrainian inability to act in their rational self-interest due to subordination that Putin did not anticipate. Russian readiness to retreat in order to attrit while Ukrainians are pushed into foolhardy advances is another symptom of that dynamic. Territorial conquest was never the Russian goal.

Willy

In general, I think for the Russians this war has been more about attrition than territory

You think? It’s understandable that millions of Ukrainians fled (90% women and children with able-bodied men held back), since that’s what civilians in war zones have been doing for millennia. But from Mother Russia? We’ve seen one of the biggest brain drain attritions in modern history, since I dunno, Indian techs left Hyderabad for Redmond. There has to be a reason for that.

So I think we’re getting fairly close to the end

Now I don’t know much about the details of wartime economies, but Putin did replace Shoigu the national defense expert with Belousov the economics expert. That move seems to imply a long wartime economy road ahead. Unless Trump gets elected I suppose.

But I do think that bruce is absolutely correct in one assessment: modern media sucks and one tends to become what media they consume. If I watch something like “The Military Show”, I see a pro-American site trying to present itself as objective. If I watch RT, the Ukrainians are always getting their butts kicked and liking it too. So what I try to do is to watch both, cross my eyes to try and see the pattern, then call that the reality. I find it interesting that nobody else admits to what media they’re consuming.

Texas Nate

Great to read Sean Paul’s work again! Welcome back.

bruce wilder

Willy thinks I am right about something!

With regard to the Ukraine War, the struggle to control the narrative has become its own theatre of operations. The first casualty of war is truth, they say. No kidding.

I do not recommend “split the difference” or “cross your eyes” when reading partisan or “mainstream” narratives. Beware of extended counterfactuals and projections masquerading as facts. Beware of factoids masquerading as facts. Beware of manufactured doubt befogging fact. Remember actual facts where you may know some and previous lies and previous liars, where they have been revealed.

In an information vacuum, memory serves to contain the vacuum.

Also, the experience of having a depth of knowledge about some other topic can be consulted for comparison — a yardstick to remind you about how little you know or how little the journalist you are reading knows about the topic at hand. Try to tolerate not knowing as best you can when you have no opportunity to learn.

Specifically with regard to Ukraine, I think many of the actual facts do not flatter any major actor or side, which is why facts are so seldom used honestly in the contest of narratives. And, mainstream journalism no longer profits from curiosity or verification. Performative verification — “fact-checking” — has become ritualized to conform to editorial policy. Genuine and honest experts are marginalized along with the kooks.

Sean Paul Kelley

Bruce Wilder:

Well said.

Allow me to add a corollary to your thoughts: the most dangerous thing an American policy-maker, politician or honest expert can be is right. Being right is the quickest, most surefire way to ruin anyone’s career.

elkern

SPK –

I should have been clearer; I was looking for an explanation of the “Rossokovsky” joke . I’d bet that it’s an off-color pun?

Soredemos

@elkern

The Moskva didn’t matter. Losing it was just embarrassing (I’m also not clear to this daybhiw it was actually sunk. I suspect it was just a Ukrainian sea mine that broke free from it’s chain and happened to float into the ship). It was something of an albatross of a vessel anyone; an outdated relic. Its sister ship had been expensively modernized and roved that probably wasn’t worth the effort. Cheaper and easier to just build something new from scratch.

The rest of the Black Sea fleet is fundamentally fine. It sits back and lobs cruise missile strikes, like it’s been doing since the start of the war. The media just loves to cheer every time something of secondary or tertiary importance like a transport vessel is hit and portray this as a stunning blow to the Russian navy. It isn’t, it’s just annoying.

Sean Paul Kelley

@elkern: did you miss this comment: https://www.ianwelsh.net/the-russian-way-of-war/#comment-152861 I think I explained my Russian language comments pretty clearly. Adding some more terrible language and explanation by way of just having some fun.

Willy

They were gonna scrap the Moskva for turtle tank armor anyways after that fire in stormy seas. (divined from Russian Defense Ministry, the BBC, Abc.au, and a couple images somebody posted on twitter).

elkern

SPK –

Yes, I read your prior comment, but I didn’t see any explanation of the “Rossokovsky” pun there, so I politely asked again.

But maybe I missed the entire point of your comment. Reading it again, I find it hard to escape the feeling that it was merely a long-winded insult. Whatever. I suppose I can take it as a lesson in the “Russian” sense of humor?

I read – and comment on – this Blog to learn, to share, and to hone ideas, not for the pissing contests.

Sean Paul Kelley

@Elkern: Oh dear. It was not intended as an insult. It was entirely self-deprecating humor gone wrong. In essence I was making fun of my own bone-headed mistake by transposing the letters in S and K in Rokossovsky. I apologize for the misunderstanding. I too am here to learn, not piss on others.

Willy

But seriously folks, there are vlogs and other places where the owners try to keep all things Ukraine-Russia real. IMO the best are hosted by speakers of both languages who stay in touch with vloggers on the inside from both sides.

They’re the ones who tend to say stuff like “so far things are uncertain” and “we’ll just have to wait and see”, when describing operations like the recent Kurst incursion. Their opinions about events don’t seem to vary much from each other, suggesting to me they’re all up on the same general facts.

Of course, they could always be plagiarizing their stuff from just one guy who secretly, is punking everybody and actually doesn’t have a clue. But this seems unlikely.

But yeah, MSNBC seems to regularly commit lying by omission, CNN does bothsider opinionation obfuscation lying, while Fox just straight up lies. I gave up on them long ago.

Curt Kastens

Willy,

When it comes to the Ukraine and Mid East and Chinese Conflicts the MSM here in Germany is as bad as that in the US and the UK MSM is even 10 times worse than the US MSM.

elkern

SPK – apology accepted unconditionally, on the condition that you also accept my apology for misinterpreting your comment!

On the internet, no one can see you smile… 😉