I was talking with a friend the other day and he said the problem with democracies is that policy can swing 180 degrees with each election.

And in some ways that’s true: Trump’s switch on Ukraine is a good example.

But it’s not true when it comes to the core goals of Western government since 1979 or so.

The ur-rule of neoliberalism is that the rich must always get richer.

Trump’s budget cuts 600 million from Medicaid, and other health care in order to give tax cuts to the rich.

Trudeau’s big change from previous Prime Ministers was to massively increase immigration. The effect was to depress wages and increase rent and real-estate prices.

When European countries talk about increasing military spending, there is the inevitable comment that this will require slashing social spending. Somehow, the idea of taxing the rich and corporations more is never raised, even though that would easily cover the cost.

DOGE’s civil service cuts will lead to massive outsourcing of whatever the government really has to do, which will cost more than doing it in house, and it will profit the rich.

Starmer’s extate taxes on family farmers will force them to sell their farms to agri-business or developers (and, overall, make the UK even less able to feed itself).

Trump’s proposal to cut the military budget massively, in concert with China and Russia, would open up more room for tax cuts. The savings won’t be used to help poor and middle class Americans, you can be sure of that. (It also isn’t going to happen that way, because China can easily afford its military budget. More on that in a later article, probably.)

This isn’t to say there are never exceptions, but they are exceptions.

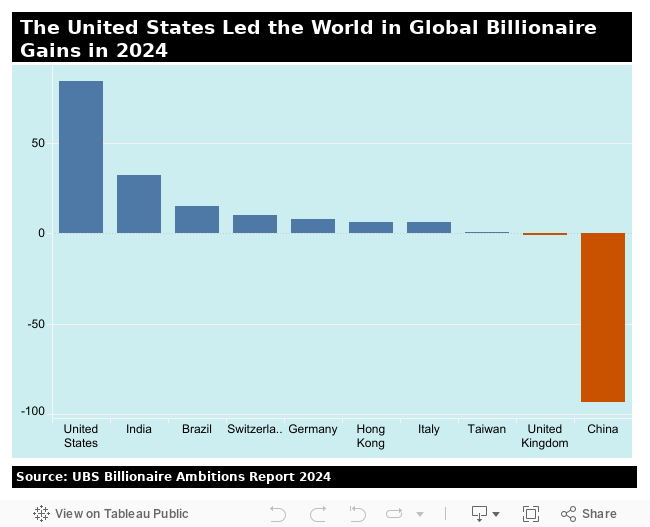

This is quite different, by the way, from China.

China used to be willing to mint billionaires, but they figured out it was harming the majority of the population, so they are dealing with it. This is one of the reasons why China has won, and the US has lost. (Another factor is that China doesn’t talk about free markets, but actually has them, while the West talks about them but makes sure they never happen.)

Neoliberalism is in the process of ending, but until the ur-rule of always making the rich richer by screwing everyone else ends, the most important part of the oligarchical state will continue. What’s really happening under Trump is the tech-oligarchs are taking the lead trace away from the banking oligarchs. It’s an internal shuffle of power, while the looting continues.

Because a broad prosperous population, combined with massive industry, is what actually makes post-industrial revolution societies powerful, American and Western decline will continue as long as the determination to fuck over ordinary people remains.

Feral Finster

The arc of history does not bend towards justice. It bends towards power.

For power is to sociopaths, what catnip is to cats. Power inevitably ends up in the hands of sociopaths, because sociopaths are the humans who will do Whatever It Takes to get power. This is the kernel of The Iron Law Of Oligarchy.

Of course, whatever else sociopaths are good at, they are not good at building lasting coalitions, because they continually betray one another, and given a choice between their own interests and those of the institutions they ostensibly serve, they will choose their own interests, every single time. “Put not your trust, in princes and saons of men, for when his breath departs, on that very day his plans perish….” This is the kernel of The Iron Law Of Institutions.

At the same time, power is What Gets Stuff Done. Not only that, but unlike Tolkien’s hobbits, humans cannot toss The One Ring into the fires of Mount Doom and be done with it. Power will not go away, and if you do not use it, there are others who surely will, and you may not like what they do with that power. Good luck getting them to give it up.

Anyway, what we are seeing with Trump is the dropping of any remaining pretense that the United States is anything other than an empire, that the old norms and pious facades were anything other than so much happy horseshit, lies told to the children about how Fluffy went to live on a big farm where he can run around all he wants.

Anyway, let’s see whether Trump can actually accomplish anything in Ukraine before taking a victory lap.

Yves Smith really does not like me, but I agree with her in this, at least:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2025/02/trump-will-end-his-option-of-walking-away-from-project-ukraine-with-his-minerals-deal.html

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2025/02/col-douglas-macgregor-why-is-trump-arming-ukraine.html

Oakchair

Even when so called anti-establishment parties enter government they often don’t make any substantial structure changes. See: Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Sweden. Though this is more a characteristic of rich Western nations.

Feral Finster

@Oakchair: If the Establishment is good at nothing else, it is very good at determining who can be co-opted, who can be bought off, who can be neutralized, who can be ignored.

Curt Kastens

The last few podcasts by Brian Berlitic have made the claim that all of this public hostility between the Trump led USA and its historical European and Canadian collaborators is just a smoke screen to more effectively continue the western policy of weakening and subverting Russia, China and Iran. If he is right and I think it is more likely than not that he is right then using Ukraine as an example of a change in policy because of an election is not a very good example.

Below is a link with an view that differs from that of Brian Berlitic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wuP6DPyqqtU

The link is from the Grey Zone.

bruce wilder

a broadly prosperous population combined with massive industry is what actually makes post-industrial-revolution societies powerful

just a side-note: the productivity of humans in agriculture and later in manufacturing has been rising steadily for many decades. output and consumption per capita continues to rise more or less steadily but (this is the big “but”), the inputs (how many workers are needed) per unit of output also declines.

When demand growth is sufficient to push output growth into territory where more resources are needed to produce, that’s a pretty easy economic problem for a society to solve happily for everyone.

When potential productivity growth outstrips output and demand growth in a sector, then resources and workers have to somehow be withdrawn from that sector even as that sector is investing in technology and new ways of doing things. That can become the source of a lot of social and political stress.

The U.S. had a huge problem in agriculture from the late 19th century as advances in farm productivity (in at least some farms and farming communities) drove declining commodity prices. Huge swathes of the country descended into poverty, people were stuck on farms that could not pay to improve or recover. This was one of the major problems underlying the economic crises of the 1920’s and the Great Depression and a problem that the New Deal was hugely successful in solving along multiple dimensions.

The New Deal solutions were corrupted in the 1970s, which is a major reason why American food is poisoning us and making us fat and unhealthy, but that is a much later part of the story.

Much the same evolution of productivity has happened in manufacturing. The auto assembly plant was a huge advance when it was introduced in 1909. The rapid development of “process” manufacturing at scale was a big part of what made American manufacturing so dominant in the 1930’s through the 1960’s. At first, “Fordism” required a lot of hands and created opportunities to make a living for many people. But gains in productivity have been steady and continuous. An automobile might have required 50 or 60 man-hours to assemble at one-time; now it might be a dozen or less. A smart phone replaces a dozen gadgets and it might still be priced at a $1000, but the cost is sinking below $200. The infrastructure behind a cellphone is a fraction of what AT&T required back in the day.

China faces this problem now. They built a huge manufacturing economy, but still not enough to employ the available workforce and though output continues to grow, albeit more slowly than a few years ago, employment opportunities are shrinking. Even with declining population, a matching of working-age population to manufacturing won’t happen for a decade more, even in favorable circumstances.

For the same reasons, the U.S. cannot leverage a return to manufacturing to increase “working class” employment or incomes. For the U.S., the inflated price structure makes the problem more acute. China can make plenty, cheap and thus give many people a good life, even if many lose substantial savings in failed housing developments and the like. The U.S. is run by people who would never consider the possibility. For Americans are so accustomed to neoliberal corruption, their concepts of ambition and accomplishment are confused with parasitic and predatory schemes. Even people who have turned to health care sector for good-paying jobs will oppose reform that would reduce costs and employment in health care. People in banking and finance would be worse even though objectively halving the FIRE sector would be great for the country — it just wouldn’t feel great to the people who had to move on.

It is a conundrum. Things will have to get worse to get better and no one wants to take the hit.

The billionaire putsch at least has the math right: reduce number of useless eaters and the consumption of the greediest few can continue to increase.

Bazarov

(This is an edited version of my comment. I prefer this one make it through moderation, please!)

China is a capitalist country with many, many billionaires. The fact that the government occasionally executes or punishes a handful does not change the fact that the Chinese economy, being capitalist, is therefore conducive to billionaire creation. According to data from 2024, China has the most billionaires in the world.

It’s somewhat blinkered to see billionaires struggling per the graph you present and not at least entertain the fact that China’s capitalist economy is also struggling. The graph could indicate that the capital owned by Chinese billionaires has lost value.

To me, this sounds more likely than some conspiracy by the CPC to hurt billionaires in 2024. Honestly, rhetoric aside, the evidence suggests the CPC is pro-billionaire. Xi just met with and smiled benevolently upon the “6 Little Dragon” tech entrepreneurs, all billionaires I’m sure.

Revelo

>The Iron Law Of Oligarchy

>The Iron Law Of Institutions

Those laws are eternal but technology changes. In particular, we now have a situation, due to computers, robotics and other types of machine intelligence where the following tendency is accelerating:

>inputs (how many workers are needed) per unit of output also declines.

Put the above together and the direction is towards oligarchy + multipolarity + exterminism. Barons of the future (whether technology, resource, financial, lawfare or other types of barons) will no longer need huge numbers of serfs to be powerful. A small number of well behaved serfs might be kept around as pets but the majority of humans will be seen as potential threats capable of launching a rebellion. Best to eliminate the threat before it gets serious and replace humans with machines. Gaza is just the beginning, in other words.

Having exterminated the majority of humans, surviving violent barons will fight each other for supremacy using armies of drones/robots.

Purple Library Guy

I’d just like to note that a decline in the amount of work needed per amount of output is only a problem under capitalism. It is fundamentally an artificial problem, which only presents as a problem if the people running society are committed to minimizing wages, which implies having a subsistence wage require as many hours of work as possible. Such people will tend to also want a reserve army of unemployed to help keep those wages down.

If you’re fine with shortening the work week, a decline in the amount of work needed per amount of output just means everyone gets more leisure. Only enough work for half the work force? 20 hour work week, problem solved. But that probably requires some kind of democratic control over the economy, AKA socialism.

Jan Wiklund

1979 is too late as a strating point. The whole thing began earlier, with the overproduction glut in the 60s.

Up to then, the industrial corporation had been able to finance its development with earned profits. But with overproduction – inability to sell – they couldn’t. They had to turn to the money markets, i.e. the rentiers, to borrow money.

And the rentiers lent, on conditions. The most important condition was that they industrial corporations must stop seing production as important. If they didn’t obey the order, their CEOs were replaced with new CEOs who obeyed.

One of the first industrial corporations to change its ways was RCA in 1968 (anyone who remember RCA? It was the world-leading home-electronic corporation). In 1968, when it had just invented the colour tv it stopped developing new products, and used its remaining profits to buy any enterprise that promised new profits – Hertz, Random House…. And all the others would follow suite within a decade.

About the same time, banking was set “free”. There used to be a lot of rules to keep banking serving the public, but around 1970 banks began to use lawless mini-countries to set up subsiduaries where things could be done without laws at all. One of the first of these ministates was Liechtenstein.

Needless to say, no government made any objection to any of these. They could have set up a bank or a few that lent money to producing corporations and producing corporations only. They could have twisted the arms of the lawless ministates to make them adopt the same regulation laws as the regular countries had. But they did nothing of this. They let the rentiers have it as they wanted.

bruce wilder

Jan Wiklund’s comment got me thinking about whether the “mechanics” behind the rhetoric of economic theory/ideology really matter or not. As an economist in a past life I mastered the rhetorical engine known as neoclassical economic theory, aka “mainstream economic” or “Econ 101”, the ideological foundation for neoliberalism. Wiklund is referring, I think, to the neoliberal takeover of politics and economic policymaking in the 1970s and the transformation of the American economy that followed — a transformation that wiped out much of the political and economic legacy of the New Deal through globalization, financialization, deregulation, and industrial disinvestment.

A couple of things have me curious. First, although I agree with Wiklund’s sentiments concerning the historic developments I presume he intends to denote, I find I struggle to understand the mechanisms he mentions. I don’t know if he is getting ‘facts’ wrong or if I simply cannot process the dialect or jargon. I have no idea what a “production glut” might denote, let alone whether I could confirm or deny that one occurred. Did corporations lose the ability to finance product development from “earned profits”? Did business corporations turn to rentiers to borrow money?

I think I know the events that occurred in the late 1960’s and 1970’s that marked the beginning of the neoliberal era, so I think I know roughly what Wiklund is talking about (and I agree that these developments are regrettable). I would tell a different narrative, but not because I would draw a different moral to the story. I would draw much the same moral as Wiklund. But, my account of “mechanisms” would be somewhat different. Like I think the advent of OPEC and the end of Bretton Woods mattered a lot in accumulating a lot of dollar-denominated financial assets in the international banking system, dollars that were not needed immediately for trade transactions but which were available to be recycled. These came on top of the Keynesian expansion of the American economy under Kennedy and the LBJ and Nixon deficit-spending (comparatively mild compared to Reagan and latter).

Does any of that “inside baseball” economic analysis really matter to politics? Wiklund and I might debate arcane details only to conclude we needed a translator to mediate our differing dialects of economics-ese. I imagine I could bore myself very quickly.

On the other hand, I think flawed economic theory is a big part of the power neoliberalism has over people’s minds, both among elites where the common dialect of “Econ 101” is a powerful means of coordinating policymaking and also in the public discourse, where “Econ 101” reasoning helps to legitimize such powerful tools of neoliberalism as “there is no alternative”, “flexible labor markets”, relieving the “burden” of regulation, and public austerity to solve problems with the arithmetic of public finance or trade. Econ 101’s fundamental history-less-ness is just one inherent flaw that advantages neoliberalism in disabling any political memory in the general public.

And, yes, Econ 101 also conveniently provides clichéd critiques that gain no traction with either policymakers or in the public discourse. The futility of those well-rehearsed but intellectually flawed formulations is part of what makes me curious. I have my own hobbyhorses of course, but the experience of having them just reinforces my sense that there is very little interest in genuinely new economic thinking. Marxist critiques are a completely spent force in the 21st century, and mainstream academic economics has been a degenerative research program since 1960s (which coincides not coincidentally with the dominance of neoliberalism). MMT is like a clown show at a children’s birthday party.

Just the fact that apparently, we only understand the implications of major economic policy choices 50 years after “we” collectively make them and even then debate whether the consequences are chosen or inevitable highlights the futility of discursive deliberation on these topics. Is that futility simply a feature of neoliberalism we could hope to overcome? How?